TWICE VIOLATED

Abuse and Denial of Sexual and Reproductive Rights of Women with Psychosocial Disabilities in Mexico

A report by Disability Rights International and Colectivo Chuhcan

Main Author:

Priscila Rodriguez, LLM, Director of the Women’s Rights Initiative for the Americas, Disability Rights International (DRI)

Investigators and coauthors:

Eric Rosenthal, JD, Executive Director, DRI; Laurie Ahern, President, DRI; Natalia Santos, Director of the Women’s Initiative, Colectivo Chuhcan; Isabel Cancino, Colectivo Chuhcan; Patricia Lopez, Colectivo Chuhcan; Roberta Francis, MA, DRI; Courtney Wilson, MA, DRI

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- I. INTRODUCTION

- II. VIOLATIONS OF SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS

- III. RESULTS OF THE RESEARCH

- 1. Myths surrounding mothers with disabilities

- 2. Lack of safe access to sexual and reproductive health services and information

- 3. Forced sterilization and contraception

- a. Forced sterilization as torture

- b. Uninformed and forced administration of contraceptives

- 4. Lack of access and discrimination against mothers with disabilities

- a. Pressure to have an abortion and give a child up for adoption

- b. Lack of access to health and reproductive services

- 5. Women with disabilities do not know their rights

- IV. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- ANNEX I. RESEARCH RESULTS

- ANNEX II. SURVEY ON THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN WITH DISABILITIES

- ANNEX III. INFORMATION SHEET AND CONSENT FORM

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IN SPANISH

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, we would like to acknowledge all the women who bravely answered the survey upon which this report is based. The questions asked are not easy to answer and for many of them, they brought back undesirable and even painful memories. We thank you for taking the time to respond and for being willing to take part in this effort to address, prevent, and stop the grave violations against sexual and reproductive rights that occur today in Mexico City against women with psychosocial disabilities.

We also acknowledge the hard work and valuable help from the women that are part of the Colectivo Chuhcan –the first organization in Mexico run by persons with psychosocial disabilities- namely: Natalia Santos, Isabel Cancino, Patricia Lopez, Rocío Saavedra, Eunice Escobar, Yvonne Lopez, and Natalia Zamudio. Their revision of the survey, in order to adapt it to the needs of women with psychosocial disabilities, was crucial. The women were also trained to apply the questionnaires themselves to other women with similar disabilities and they showed great commitment and empathy with the women, many of whom had suffered the same abuses they did. This is the first report in Mexico produced by women with disabilities as human rights investigators. This is a revolutionary approach in the spirit of Article 4(3) of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), according to which persons with disabilities should be included in processes that address their rights. We are convinced that their close participation adds very special value to this research and we are also glad to see how being a part of it has assisted them in their process to become empowered women, defenders, and spokespersons for their own rights.

We extend a special recognition to the three psychiatric institutions and two clinics in which this survey was applied. We thank the authorities for allowing us to go inside and interview the women that receive outpatient consultations in their facilities. In general, we urge institutions to become more transparent and open to human rights investigators. It is concerning that in many institutions we were denied access to the women, who should be the ones to decide if they want to take part in research and not the authorities. Lack of access to institutions makes this particular group very hard to reach and thus, more vulnerable to abuses.

We would like to thank the Overbrook Foundation as the lead funder of this report. We would also like to thank DRI’s International Ambassador Holly Valance, The Holthues Trust, a major anonymous donor, the Open Society Foundations, and many other individual and foundation donors to DRI for making this work possible.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In Mexico there is very little information available on the situation of sexual and reproductive rights of women with psychosocial disabilities. 1 This is in direct contravention of Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (hereinafter ‘CRPD’ or ‘Convention’), according to which, “States Parties undertake to collect appropriate information, including statistical and research data, to enable them to formulate and implement policies to give effect to the Convention.2 ” This report is the first of its kind. Its main purpose is to lay the foundation for further advocacy efforts to guarantee the sexual and reproductive rights of women with disabilities at the legislative and policy level in Mexico. In this regard, it should be noted that in September 2014, Mexico was evaluated by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) for the first time. The preliminary results of this research were presented before the CRPD Committee and were included in the Committee’s Concluding Observations and recommendations to the Mexican State. 3 This research and the recommendations by the CRPD Committee will prove to be a valuable tool for further advocacy on this relevant but long ignored issue.

The present report is based on the results of a year-long study carried out by Disability Rights International (DRI) together with the Women’s Group of the Colectivo Chuhcan –the first organization in Mexico directed by persons with psychosocial disabilities. This research included the application of a questionnaire to fifty-one women with psychosocial disabilities who were either members of the Colectivo Chuhcan or received outpatient services at four different health clinics and psychiatric institutions in Mexico City. We recommend this research be extended to the rest of the country to gain a better understanding of the sexual and reproductive rights of women with disabilities at a national level.

The main finding of this report is that the Mexican government has failed to implement policies that ensure that women with psychosocial disabilities have safe access to sexual and reproductive health services, on an equal basis with others. Particularly disturbing is the fact that in Mexico City, more than forty percent of the women that were interviewed have suffered abuse while visiting a gynecologist, including sexual abuse and rape. Equally worrying is the high rate of sterilization that we documented. More than forty percent of the women had been sterilized either forcefully or had been coerced by family members to undergo the surgical procedure. The findings of this survey must be understood in the context of DRI’s broader work in Mexico, in which we have found pervasive abuses and violations of reproductive rights among women and girls detained in institutions. In June 2014, for example, DRI visited “Casa Hogar Esperanza”, an institution for children with disabilities, which has a policy of forceful sterilization of every girl that is admitted to the facility. Given the pervasive problems of sexual violence in institutions that DRI has observed in Mexico and around the world, it is our view that the main purpose of forceful sterilization of women with disabilities worldwide is to cover up sexual abuse by preventing a pregnancy that can result from it. Some women that participated in this study reported to DRI investigators that they were sterilized for this reason. DRI researchers also found this to be the case in the institution “Casa Esperanza”.

By allowing the forceful sterilization of girls and women with disabilities, particularly in institutions under the direct authority of the government, Mexico is violating their right to respect for their physical and mental integrity (Article 17); their right to retain their fertility on an equal basis to others (Article 23); their right to be free from violence, exploitation and abuse (Article 16); and their right to decide for themselves (Article 12), all of which are enshrined in the CRPD.

Moreover, this report also finds that there is a lack of government programs that address the sexual and reproductive needs of women with psychosocial disabilities. As a result, more than fifty percent of the women interviewed stated that they knew little or nothing about sexual and reproductive health. We also found that for pregnant women with disabilities in Mexico, seeking prenatal care and delivering the baby becomes a very difficult and even traumatic experience. Discriminatory practices, and particularly the fear of being forced to have an abortion, prevent women with disabilities from accessing maternal health care. For those who do manage to have their babies, there is no government support to carry out their child-rearing responsibilities, all of which is in violation of Articles 23 (right to a family) and 25 (right to health) of the CRPD.

Women with psychosocial disabilities are especially vulnerable to abuse in Mexico because the law permits the restriction of the legal capacity of persons with disabilities in violation of Article 12 of the CRPD. By doing so, Mexico’s law may deny a woman’s right to get married and to form a family. For a man or woman who is placed in an institution, the violation to his/her right to legal capacity is even more severe given that, as soon as that person is admitted to an institution, he/she loses the right to make even the most fundamental daily decisions of life – with no legal process whatsoever. In our 2010 report Abandoned and Disappeared, DRI found grave violations to the sexual and reproductive rights of women with disabilities in psychiatric institutions. For the present study, however, we were not able to gain access to women that have been institutionalized. It should be noted that, despite the fact that the women we interviewed live in the community and have attained a significant degree of independence, we found an extremely high rate of abuse. We know that the incidence of abuse in institutions is considerably higher; women with disabilities detained in these places face all type of abuses, from physical and sexual abuse to trafficking. We call on the government of Mexico to allow DRI and the Colectivo Chuhcan to extend our study to institutionalized women in psychiatric facilities, orphanages, and other institutions throughout Mexico. We further recommend that the situation of the sexual and reproductive rights of women with disabilities in psychiatric institutions be investigated by human rights authorities in an in-depth and urgent manner.

I. INTRODUCTION

1. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD or the ‘Convention’) came into force in May 2008 and is the first new human rights treaty of the 21st century.4 The treaty is considered revolutionary in that it rejects the medical model of disability, which focuses on the need to care for, treat, and protect persons with disabilities. Instead, the treaty embraces the social and human rights models of disability, which recognizes people with disabilities as rights holders before international law and views their disability as a result of their condition but also, and more often so, of the physical and attitudinal barriers they face in society, government policies, and in legislation. The general principles of the Convention, as outlined in Article 3, are:

“[…] respect for the inherent dignity, individual autonomy —including the freedom to make one’s own choices—, and independence of persons; non-discrimination; full and effective participation and inclusion in society; respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity; equality of opportunity; accessibility; equality between men and women; and respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identities”. 5

According to Petersen, the common observation that the CRPD does not create new rights understates its content and potential impact. Even though it can be argued that most of the rights enshrined in the CRPD have been recognized in other treaties,6 the Convention “fundamentally enriches and modifies the content of existing rights when applied to people with disabilities, often by reformulating and extending rights.” 7 In this regard, the CRPD moves away from the traditional distinction between “civil and political” rights and “economic, social, and cultural” rights. Instead, the CRPD embraces a more holistic view of what human rights mean for persons with disabilities.

The government of Mexico is the world’s leader in bringing about international recognition of the rights of people with disabilities under international law.9 In December 2001, Mexico introduced a resolution at the United Nations General Assembly to create a committee that would “consider proposals” for drafting a new convention on the rights of persons with disabilities.10 With support from Mexico, the United Nations convened drafting sessions that included disability leaders, human rights experts, and governments around the world to draft the CRPD. The drafting of the CRPD was completed in less than five years, a short period of time given the large number of participants, submissions and highly controversial issues. The CRPD was adopted by the United Nations on December 13, 2006, and it entered into force as binding international law on May 3, 2008, after the first twenty countries ratified it. The Convention has since gained worldwide support with unprecedented speed.11 As of February 2015, 158 countries have signed the CRPD and 147 have ratified it.12

Predictably, Mexico was one of the first countries in the world to ratify the CRPD and its Optional Protocol on December 17, 2007.13 By ratifying the Convention, Mexico agreed to “adopt all appropriate legislative, administrative and other measures” necessary for implementation of the rights established therein. 14 Every State that ratifies the Convention also agrees to report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) on the steps it is taking “to give effect to its obligations” in relation to the implementation of the treaty. 15 The UN CRPD Committee then issues an assessment of the country’s steps toward implementation of the CRPD.

The CRPD Committee evaluated Mexico for the first time in September 2014. For the evaluation, the Mexican Government submitted a report to the CRPD Committee and Disability Rights International (DRI), together with other civil society organizations, submitted an alternative report –also known as shadow report. 16 Our alternative report included the documentation of DRI’s Report Abandoned and Disappeared17 on the situation of Mexico’s population of children and adults with disabilities who are detained in institutions. DRI’s Alternative Report to the UN CRPD Committee showed that, despite its commitment to the rights of persons with disabilities at the international level, Mexico continues to systematically violate the rights of persons with mental disabilities and, in particular, their right to live in the community (Article 19 of the CRPD).

As a country that is recognized as the international promoter of the Convention and one of the first countries to sign and ratify it, there was a pressure on the government to conform to the high expectations it had set for itself. However, the evaluation of the Committee was overall negative. After the session held in September, the Committee issued its Concluding Observations where it found that there were grave violations against the rights of adults and children with disabilities in Mexico, including segregation of persons with disabilities in dangerous institutions, and recommended the State address them. Some of the most relevant recommendations in relation to the right to live in the community, a direct result of DRI’s advocacy before the Committee, include:

- a) Repeal the legislation that allows for detention based on disability and ensure that all mental health services are provided based on the free and informed consent of the person concerned.18

- b) Adopt legislative, financial and other measures necessary to ensure independent living in the community for people with disabilities.19

- c) Urgently create a strategy to de-institutionalize people with disabilities, [this strategy must have] specific deadlines and follow up on results.20

2. Sexual and reproductive rights of women with disabilities

Historically, women and men with disabilities have been prevented from exercising their sexuality and forming families. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, eugenic theories started gaining in popularity around the world. These theories promoted the ‘improvement of the population’ by preventing persons to be perceived as ‘inferior’ or ‘unfit’ from reproducing.21 Thus, it is no surprise that the eugenic laws and policies that resulted from these theories have an intimate and grievous history for persons with disabilities, who were – and still are – regarded as ‘sick’, ‘defective’ and ‘flawed’. 22 In this respect, early proponents of eugenics “portrayed disabled women in particular as unfit for procreation and as incompetent mothers.”23 As a result, many women with disabilities in various countries were subjected to forced sterilization and other practices to prevent them from reproducing.

Mexico itself has a history with eugenics. In December 1932, the state of Veracruz, located in eastern central Mexico, became the only place in all of Latin America to pass a eugenic sterilization law. This law was considered by the local government at the time to be a “protective measure in the interest not only of the species and the race, but also beneficial for the home” and “salubrious for the family”. 24 In July 1932, Law 121 founded the Section of Eugenics and Mental Hygiene, which was charged with studying “the physical diseases and defects of the human organism, susceptible of being transmitted by heredity from parents to children.”25 An extensive addendum was passed six months later; this addendum granted the state much greater authority to pursue the public health interventionism characteristic of preventive eugenics. Its preamble stated that it was time for Veracruz to pursue the goals of Mexico’s revolutionary government by ensuring the “conservation and betterment of the physical and mental state of citizens”. 26 To this end, the legislation called for the “regulation of reproduction and feasible applications of a methodical eugenics”, including legal sterilization of “the insane, idiots, degenerates or those demented to such a degree that their defect is considered incurable or hereditarily transmissible in the judgment of the Section of Eugenics and Mental Hygiene”. 27 Eighty-three years later, this law has not yet been abolished.

In light of the painful history of eugenics, it is not surprising that the drafters of the CRPD would want to address the issues of life, marriage, and reproduction.28 As such, Article 23 (Respect for home and the family) calls for the elimination of discrimination against persons with disabilities in all matters relating to marriage, family, and parenthood. It also expressly requires States Parties to provide education and services to enable persons with disabilities to decide “freely and responsibly” on the number and spacing of their children, and to render appropriate assistance to persons with disabilities in the performance of their child-rearing responsibilities.29 Article 25 (Health) requires States Parties to provide persons with disabilities with equal access to sexual and reproductive health services.30 Article 17 (Protecting the integrity of the person) includes the prohibition of forced sterilization, which has been considered a form of torture by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.31 This report focuses especially on Article 23, but touches upon the other articles as well.

Article 23 establishes the negative right to be free from government interference when deciding whether to marry and when to reproduce. However, Article 23 also endows persons with disabilities with a positive right to receive education and services that may be necessary for them to give birth to, and care for, their children.32 Of particular importance is section 4 of Article 23 which states that no parent and child should ever be separated on the basis of disability, as well as section 5, which articulates that States Parties should provide alternative care to children when the immediate family is unable to care for them. Finally, Article 23 states that “persons with disabilities, including children, retain their fertility on an equal basis with others”.33

3. Right to legal capacity and the right to form a family

Article 23, Clause 1 establishes that all persons with disabilities have the right to marry and start a family. Subparagraph a) specifically requires that State Parties take effective and appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against persons with disabilities in all matters relating to marriage, family, parenthood and relationships. It also recognizes the right of all persons with disabilities who are of marriageable age to marry and to found a family on the basis of free and full consent.34

Sexual and reproductive rights and the right to form a family are inextricably linked with the right to legal capacity – to make decisions over one’s life – recognized in Article 12 (equality before the law). According to the Committee, the right to legal capacity consists of two parts: 1) the legal standing to hold rights and to be recognized as a legal person before the law; and 2) the legal agency to act on those rights and to have those actions recognized by the law.35 As such, Article 12 is regarded as one of the Convention’s pillars and core values. The ability to make decisions that have a legal effect is instrumental to exercising all the other rights recognized in the treaty.36 In its first General Comment, the UN CRPD Committee is very emphatic when stating “there are no permissible circumstances under international human rights law in which a person may be deprived of the right to recognition as a person before the law, or in which this right may be limited”. 37 Regrettably, according to the Committee, the right to make decisions that have legal effect “is frequently denied or diminished for persons with disabilities”. 38

According to the CRPD Committee, “there has been a general failure to understand that the human rights-based model of disability implies a shift from the substitute decision-making paradigm to one that is based on supported decision making”. 39 This is the case in Mexico, where a person’s rights can be overruled by the legal system if he/she is declared mentally incompetent and appointed a guardian. Persons with disabilities under the guardianship regime are unable to make decisions and instead, the guardian will make them for them, substituting their will.40 The violation of the right to legal capacity in Mexico is a grave violation of the sexual and reproductive rights of persons with psychosocial disabilities, especially of those detained in institutions, as evidenced in this report – given that the women cannot decide over their own bodies. It is important to point out that the denial of legal capacity is not only de jure but also de facto. We have documented that for a woman to be sterilized in a forced or coercive manner, she does not need to be under guardianship; it is enough if her parents give their consent (see Section III 3a of this report).

The denial of legal capacity worldwide has its own link to eugenic theories as it has been used to prevent persons with disabilities from marrying and having children. One of the most extreme examples of eugenics policies were the policies in Nazi Germany during World War II that led to the extermination of millions of Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, and people with disabilities. However, laws reflecting eugenic theory did not end after World War II and have continued in some nations,41 including the United States, where six states have laws that restrict marriage (or provide for annulment) on the grounds of disability.42

Similar to the US, Mexico has laws that restrict the legal capacity of persons with disabilities and as a result restrict their right to get married and form a family. Article 450 of Mexico City’s Civil Code (from here onwards Civil Code) states that minors and persons with disabilities have ‘natural’ and ‘legal’ incapacity, and refers to them as ‘incapacitated’. Article 156, Section X of the Civil Code states that persons declared ‘incapacitated’ cannot get married. For persons that were already married when they developed a psychosocial disability, the Civil Code establishes that:

- a) The spouse can have the marriage annulled. Article 247 states that “the spouse, [and] the guardian [of the ‘incapacitated’] […] have the right to request the nullity [of the marriage] referred to in Article 156, Section X [of the Civil Code].” Article 277 states that “a person who does not want to file for divorce may, however, request that their obligation to cohabit with their spouse is suspended in any of the following cases: [he/she] suffers an incurable mental disorder, with a prior declaration of the ‘incapacity’ of the ill spouse.”43

- b) If the marriage is not annulled, the spouse will automatically become the guardian of the person with the disability. Article 486 of the Civil Code states that “guardianship over the spouse declared incapacitated, corresponds necessarily and legitimately to the other spouse.”

- c) By becoming the guardian, the spouse will make all decisions on who the children live with and about their upbringing. Article 447 Section I states that parental rights are suspended for a person that has been declared legally ‘incapable.’44 Article 465 states that the children of an ‘incapacitated’ person will be under the guardianship of the family member that the law establishes, if there are no family members, they will be assigned a guardian. Thus, a person that develops a mental disability automatically loses guardianship over his/her own children.

In this regard, the UN CRPD Committee recommended that Mexico “review and harmonize its Civil Code to ensure the rights of all persons with disabilities to marry and have custody of their children”. 45

The violation of losing one’s legal capacity is exemplified by the case of one woman who reported to DRI that after she developed a psychosocial disability, her husband was designated as her guardian, placed her in an institution against her will, and denied her all access to her children.46 This also serves to show how violations of the rights of persons with disabilities in institutions are more severe.

A person who is placed in an institution loses the right to make even the most fundamental daily decisions of life – with no legal process whatsoever.47 In 2010, DRI documented several cases of institutionalized women who were denied parental rights as a result of being placed under guardianship. The director of the institution acts in practice as his/her guardian and will henceforth make all decisions concerning him/her. 48 In its 2010 Report, DRI interviewed the Director of Hospital “Adolfo M. Nieto”, a long-stay psychiatric hospital for women in Mexico. At this hospital, DRI came across a pregnant woman. When asked what would happen to the child, the director reported that the baby would be taken away from her and put up for adoption because she is detained at the facility. When investigators pressed the director as to whether any improvement in her condition might make a difference to the outcome of this case, the director made it clear that the decision was entirely in the hands of the institution authorities and that her current placement in the facility was an adequate justification for having the child removed – whether or not her mental condition improved by the time the baby was born.49

The subject of this report is sexual and reproductive rights - addressed more in-depth in the following section. However, if these rights are to be fully guaranteed, persons with disabilities must remain integrated in the community (Article 19 of the CRPD) and be recognized before the law as persons that can make decisions with legal effect (Article 12). This section demonstrates that the rights enshrined in the CRPD are interlinked and in order to guarantee any particular right, all rights must be guaranteed.

II. VIOLATIONS OF SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS

1. Methodology

In Mexico, there is a lack of much-needed research into the rights of women with disabilities and, specifically, on their sexual and reproductive rights. In its Concluding Observations to Mexico, the UN CRPD Committee recommended that the state “systematically collect data and statistics on the situation of women and girls with disabilities with indicators that can assess the intersectional discrimination.”50 Until this report, the only study in Mexico on the rights of women with disabilities was conducted by the National Institute for Women (Inmujeres for its Spanish acronym) in 2002. 51 This study focused on all types of disabilities and a broad range of rights. The research recognized that especially in the area of sexual and reproductive health, the issue of disability and gender ‘has received very marginal attention’. 52 Twelve years later, the current report is the first and only research to focus solely on sexual and reproductive rights of women with psychosocial disabilities in Mexico.

The aim of this research is to identify the main violations against the sexual and reproductive rights of women with psychosocial disabilities in Mexico City. It provides important primary data that will be used as evidence for the advocacy of sexual and reproductive rights of women with disabilities in the country. The preliminary results of this research were presented before the CRPD Committee for Mexico’s evaluation in September 2014 (see Section I.1.a). The Committee showed concern about the violations we presented and, in its concluding observations, incorporated many of our recommendations to the Mexican government.

The primary strength of this research is the involvement of women with disabilities. This research is based on the idea that women and mothers with disabilities ‘have much to teach us – if we are open to such teachings’.53 In accordance with the UN CRPD principle “nothing about us without us,” women with psychosocial disabilities were involved in every stage of this report, including planning, design, implementation, and systematization of the findings. This was achieved through direct collaboration with the Women’s Group of the Colectivo Chuhcan – the first organization in Mexico directed by persons with psychosocial disabilities.54

The research is divided into two parts; the first part consists of quantitative research based on a questionnaire (see Annex II) designed by DRI and women from the Colectivo. The women of the Colectivo were the first ones to answer the questionnaire and to provide feedback, based on which any necessary changes were made. Once the questionnaire had been amended to suit the specific needs of women with disabilities in Mexico City, the Colectivo women received training from DRI on how to apply the questionnaire. Following the training, the women’s committee members applied the questionnaire in various psychiatric institutions. This was particularly empowering as it ensured that women with disabilities were not only involved in the crafting of the questionnaire but were also trained to become human rights investigators. Recruiting the Colectivo women as researchers also meant that an element of trust and rapport was built between the researcher and participant – a key element of this research.

Women from the Colectivo Chuhcan: (above from left to right) Isabel Cancino, Natalia Zamudio, Rocío Saavedra, Patricia Lopez, Eunice Escobar, Yvonne Lopez, (below from left to right) Susana, Natalia Santos

It should be noted that women with psychosocial disabilities are a very difficult group to access. In the best-case scenario, they are overprotected by their families and remain segregated at home, and in the worst, they have been institutionalized. In DRI’s experience, access to psychiatric institutions in Mexico is extremely hard and trying to get time in private with women to apply a questionnaire is nearly impossible. Thus, in order to be able to apply the questionnaire we decided to focus on the outpatient services of psychiatric institutions and interview women that live in the community with their families but receive mental health care or rehabilitation at the outpatient services. In total, the questionnaire was applied to 51 women over a period of seven months. We interviewed women in the following psychiatric institutions/clinics:

- Clinic No. 23 of the Mexican Institute for Social Security (IMSS), under the authority of Mexico City’s Government.

- Psychiatric Hospital of the IMSS, under the authority of Mexico City’s Government.

- National Psychiatric Hospital Ramón de la Fuente, under the authority of the Federal Government.

- Psychiatric Hospital Fray Bernardino Álvarez, under the authority of the Federal Government.

The women that were interviewed were first given a consent form that included an information sheet on the purpose of the research and its contents (see Annex III). In the information sheet we emphasized the fact that the women did not have to answer a question if they did not feel comfortable or they did not want to. Thus, some questions were not answered by all the women. The percentages presented in this report are in relation to the number of women that answered the question. In order to see details on the number of answers for each question please see Annex I, which includes detailed charts on the results obtained. Once the women had read the information sheet and agreed to take part, they proceeded to answer the questionnaire (see Annex II).

The second part of this research is of a qualitative nature and is based on interviews with women and mothers with psychosocial disabilities. An interview can be an effective way to give voice to people who usually have no opportunity to share their concerns or get their experiences out in the open.55 Six women of the Colectivo – two of whom are mothers – were interviewed.

2. Need to expand the research to include women in institutions

It is important to note that the women interviewed for this questionnaire are not entirely representative of all women with psychosocial disabilities in Mexico given that they are, to a certain degree, independent. As already noted, the women that were interviewed in the outpatient services of psychiatric institutions attend these services on their own. While this allowed us to interview them freely without family members being around to potentially suppress their views, this also meant that they are, in general terms, ‘better off’ than the majority of women with psychosocial disabilities in Mexico. Likewise, the women of the Colectivo that were interviewed have been empowered through the Women’s Group and have attained a certain degree of independence within their own families.

As such, this research does not aim to be representative of the situation of women with psychosocial disabilities in Mexico, the majority of whom are segregated at their homes or in abusive institutions, but rather indicative of the violations experienced by this group. Bearing in mind that the women we interviewed are empowered to a certain degree, the high rate of abuse that we have found in this ‘better off’ group of women, as detailed in the next section, is very disturbing and it signals even higher rates of rights violations against women segregated at home and in institutions.

DRI’s 2010 Report Abandoned and Disappeared finds that the gravest violations to the sexual and reproductive rights of persons with psychosocial disabilities take place in these institutions. As documented in Abandoned and Disappeared, there are extensive violations of the sexual and reproductive rights of women who have been institutionalized. We recommend that Mexican authorities urgently investigate both the abuses against women that are segregated in their homes and abuses in institutions.

III. RESULTS OF THE RESEARCH

1. Myths surrounding mothers with disabilities

I have been repeatedly told that I should not have children because I might pass on my disability to them. I do not have children. – Woman with a psychosocial disability

Not a single day goes by without someone telling me that I am very irresponsible and that I brought my child to this world to suffer – Mother with a psychosocial disability

Women with mental disabilities have been historically regarded as asexual, dependent, and incapable of raising children and making appropriate choices regarding reproduction.56 To disqualify a woman from any activity on the grounds of her disability is plainly discriminatory and contrary to the principles of the CRPD. People with disabilities have limitations due to their individual conditions and may face challenges in carrying out daily life activities, which include parenting. However, with adequate support and reasonable adjustments, as mandated by the Convention (Article 2), people with disabilities have the ability – and the right – to play significant roles in society, including being parents, on an equal footing with others. States are not only obliged to provide people with disabilities with the supports they need, but to also eliminate the barriers they face in society, including stereotypes about disability and specifically about sexuality and reproduction.

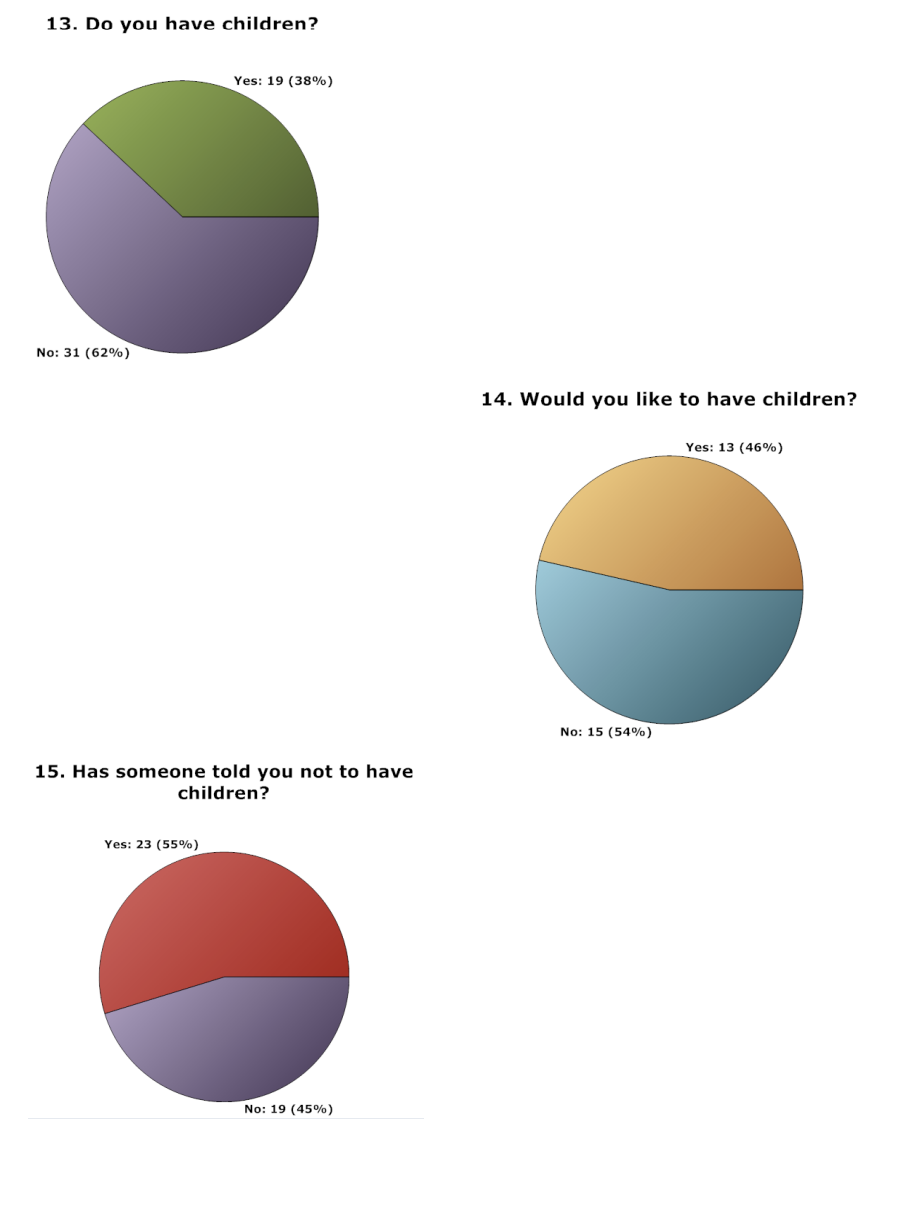

In spite of this, girls with disabilities grow up thinking that they will never be able to get married or have children.57 More than 50 percent of the women surveyed for this report were told that they should not have children (Annex I, chart 15). A woman with a disability wrote: “according to the cultural and socially constructed beliefs I was brought up with, it is non-disabled women’s responsibility to reproduce, and I, as a woman with disabilities could not, and should not, reproduce”. 58

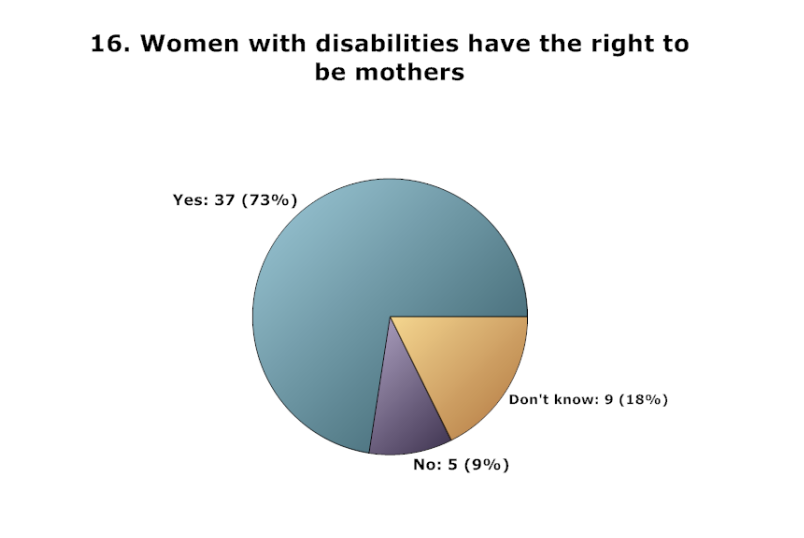

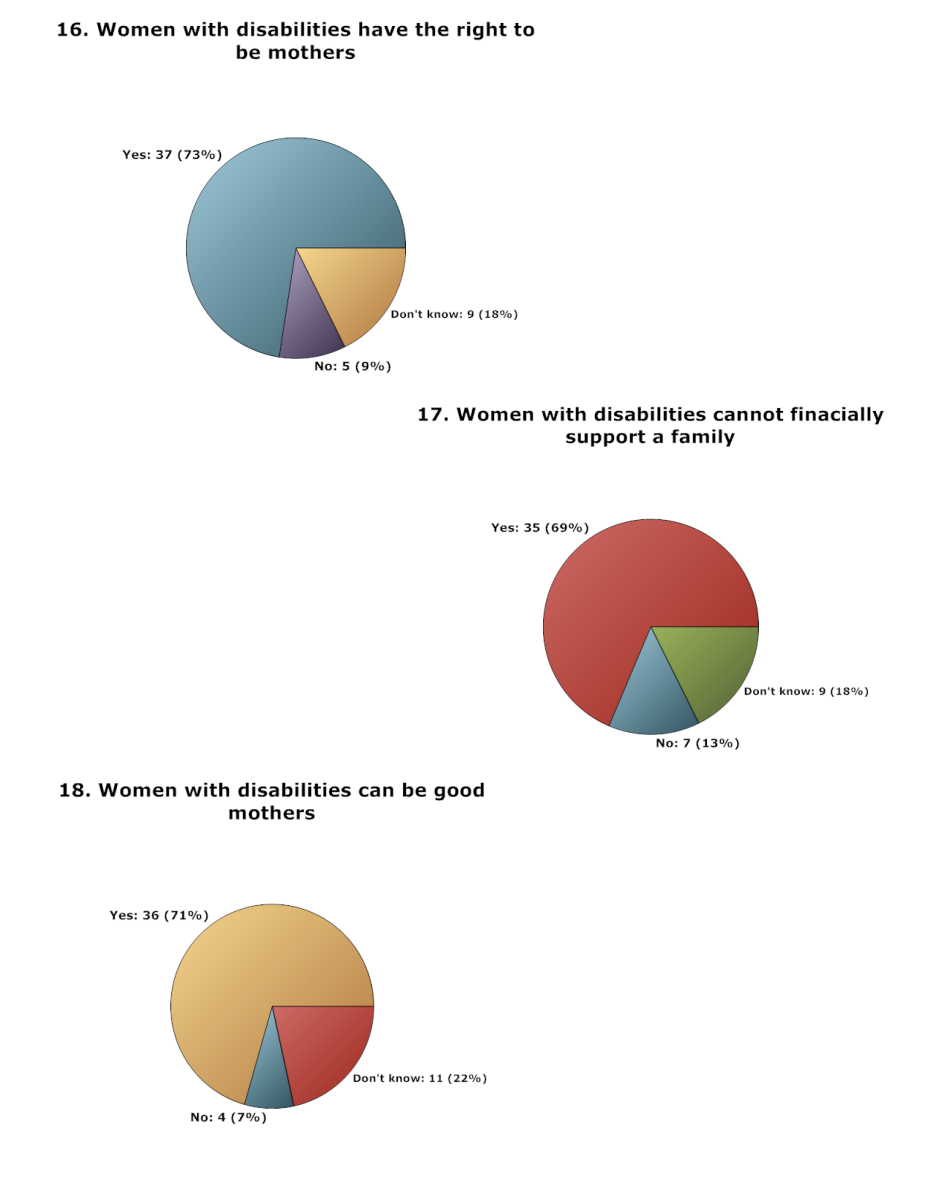

It is important to combat stereotypes against women with disabilities because they are likely to internalize and believe the stereotypes that surround them. When a woman internalizes the stereotypes that she is ‘asexual’ or that she will never have children, she may “end up giving up every plan or dream to form a family or have a partner”. 59 This is consistent with the findings of our research. Thirty-six women (71%) believed that women with disabilities could be good mothers (Annex I, chart 18) and 37 women (73%) agreed that women with disabilities had the right to have children (see chart 16, below). However, only 13 women answered that they would like to have children (Annex I, chart 14).

Echoing the stereotype that women with disabilities are dependent and will remain dependent all of their lives, 69 percent of the women interviewed believed that women with disabilities cannot financially support a child (Annex I, chart 17).

There are two main stereotypes which society uses to ‘explain’ why women with disabilities should not have children: 1) that they will pass on their disability to their child, and 2) that they cannot be good mothers. 60 Regarding the former, women with disabilities are thought to be ‘contagious’ because they are ‘unhealthy’ and are therefore questionable in terms of their ability to give birth to a ‘healthy’ child.61 Many women who took part in this research report that they were repeatedly told that they cannot have children because the child will be born with a disability. There is also a widespread assumption that if a woman with a disability gets pregnant, there are “risks to the health and survival of the foetus and the disabled mother”. 62

This report will not address the validity of these stereotypes, with the exception of the following points: 1) these beliefs have a basis in eugenics, which seeks to eliminate disability in society; 2) disability is not a 'disease' but rather, in accordance with the CRPD, is a condition that interacts with the barriers imposed by society and 3) by assuming that disability is a disease, allowing certain women and men with 'diseases' which can be hereditary to reproduce, and not others, in particular women with disabilities, is a logical fallacy with grave personal consequences that results in discriminatory acts that violate the rights of women with disabilities.

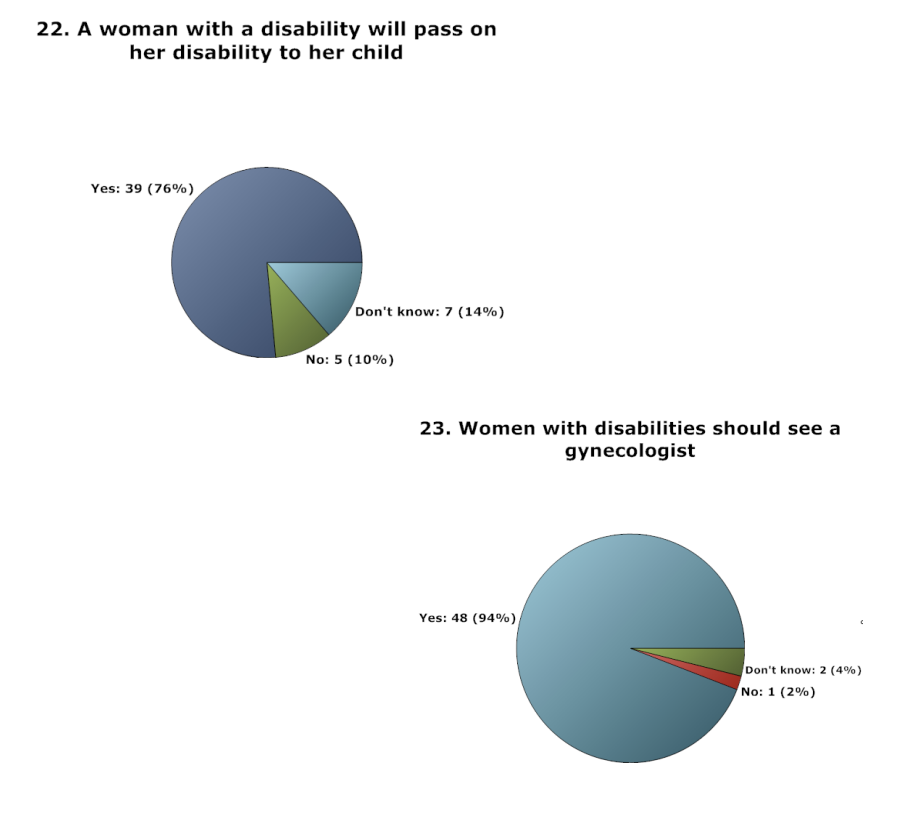

According to the results of our research, women with disabilities in Mexico have internalized these stereotypes. Seventy-seven percent of the women interviewed believed that if a woman with a disability got pregnant, she would pass on her disability to her child (Annex I, chart 22). According to the literature available, “the offer to disabled women of […] genetic testing serves a eugenics impulse to disappear ‘abnormal conditions’ through abortion or the prevention of pregnancy”. 63 More than 60 percent of respondents believed that a woman with a disability should undergo medical tests before considering pregnancy to prevent her from passing on her disability (Annex I, chart 21).

Women with disabilities who go beyond these stereotypes and ‘dare’ to consider having children are more often than not perceived as irresponsible by society. Women with disabilities who get pregnant are often labeled as reckless, careless and even egoistic for ‘not thinking what they can do to the child’. 64 For instance, the 2001 Inmujeres report shows the case of a 36-year-old teacher who was Deaf. Doctors in the social security system scolded her for getting pregnant, calling her irresponsible for not considering the risk of passing her disability on to her daughter.65

The following testimony of a woman with a psychosocial disability summarizes the strong resistance these women face even when they consider having children:

“When I became pregnant the whole world told me: ‘you are not going to be able to do this’. My child is eight-years-old and to date, when she throws a tantrum, and even though I am doing everything I can to deal with her, they immediately jump on me and start yelling at me ‘you should not have had her’ and ‘you were very irresponsible to have her’. This hurts a lot because she is one of the brightest joys in my life and because they do not see everything I have fought and achieved to have her. There are some things in which I will fail but I make a huge effort to make sure that she will have everything she needs. Nevertheless, not a single day goes by without someone telling me that I am very irresponsible and that I brought my child to this world to suffer. My mother keeps telling me that my daughter was a mistake. […] Just because I have a disability, my family thinks that I do not have the ability to decide and take care of my child. They question every decision I make. It is very hard. Having a disability does not make me a bad mother or an incapable person, but I have realized that it does mean that everything I do will be questioned and criticized more than if I did not have a disability.”

It is thus crucial that programs are developed to address the stereotypes against women with disabilities and educate and sensitize society on the rights of this group. These programs must also be specifically designed to empower women with disabilities to know and advocate for their rights.

2. Lack of safe access to sexual and reproductive health services and information

I was having a psychiatric crisis and I had to see a gynecologist. Since I was having a crisis they refused to provide me with the care I needed. Not only that, I was also mistreated, mocked and ridiculed. – Woman with a psychosocial disability

Article 23, clause 1, subparagraph b) of the CRPD requires States to recognize “the rights of persons with disabilities to […] have access to age-appropriate information [and] reproductive and family planning education”. Reproductive education and health is indistinguishable from considerations of reproductive rights and choice. However, family planning and reproductive health services have not been accessible to women with disabilities or have largely been aimed at preventing women with disabilities from having children.66

Access to information is a basic human right. According to Article 21 of the CRPD, States Parties must ensure that persons with disabilities can exercise the right to freedom of expression and opinion. This includes the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and to access that information in an appropriate format and in a timely manner without additional cost.67 All women, regardless of their disability, have the right to access information they can understand and to make an informed decision about prescribed medication (CRPD Article 3a). If a person does not understand the provided information, it is the state’s responsibility to find an alternative method of communication (Article 4h, Article 9f, Article 21). Research shows that many women with disabilities do not have the information or access to health services to make informed decisions.68 In Mexico, the assumption that women with disabilities are incapable of raising children has resulted in a lack of access to sexual and reproductive health services.69

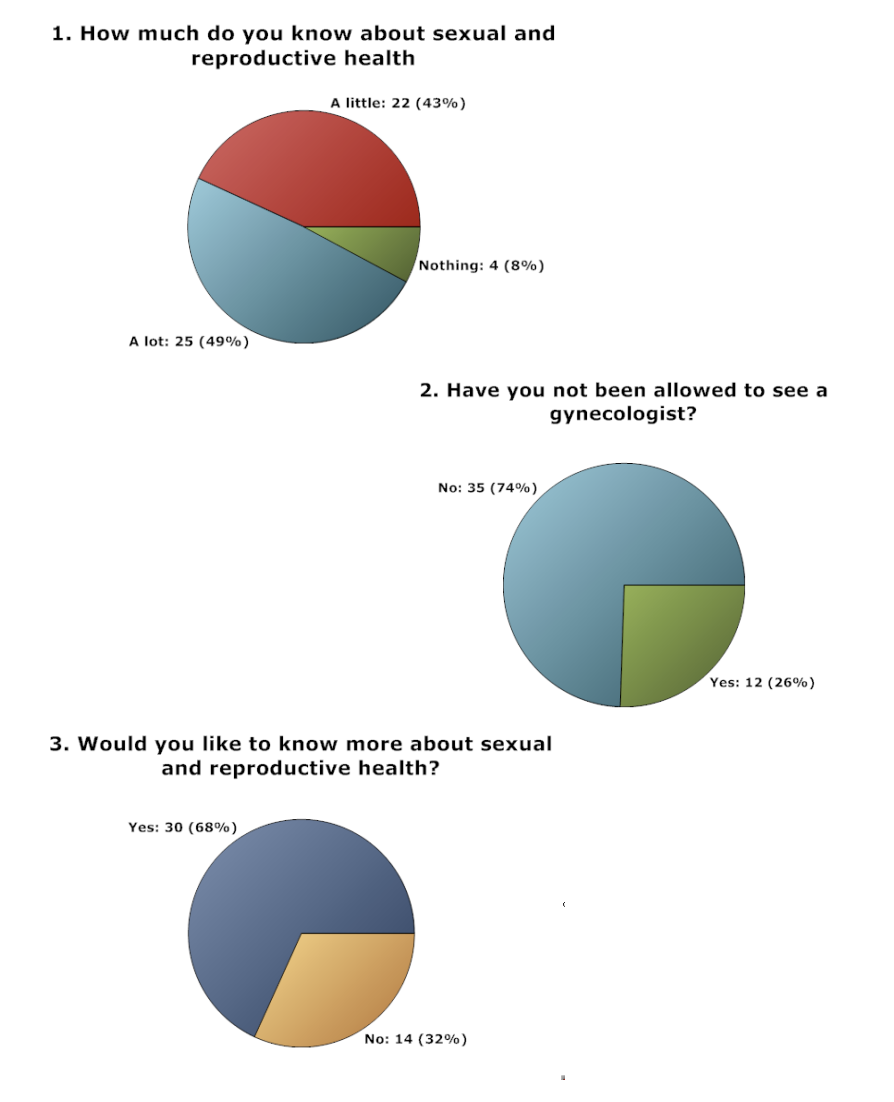

One of the multiple barriers that women with disabilities face is the medical sector's reluctance to accept that they need to be included in sexual and reproductive health programs available for women. 70 Furthermore, the majority of information on sexual and reproductive health is not accessible for women with disabilities as it is not available in Braille or in accessible language. 71 Despite pressure from civil society organizations, including Confederación Mexicana de Asociaciones en Favor de la Persona con Discapacidad Mental A.C. (CONFE), there are no government programs developed to address the sexual and reproductive needs of women with mental disabilities. 72 In this regard, it is not surprising that more than 50 percent of the women interviewed stated that they knew little or nothing about sexual and reproductive health (Annex I, chart 1). When asked whether they would like to know more about it, almost 70 percent answered ‘yes’ (Annex I, chart 3).

Even more worrying is the Mexican government’s failure to implement policies that ensure that women with psychosocial disabilities have access to safe sexual and reproductive services. The research carried out by Inmujeres in 2002 showed that in Mexico, women with disabilities rarely visit the gynecologist.73 All of the women we interviewed were of reproductive age but only 35 percent visit the gynecologist regularly. Sixty-five percent of the women stated that they do not visit the gynecologist regularly or had never/almost never been to one (Annex I, chart 4).

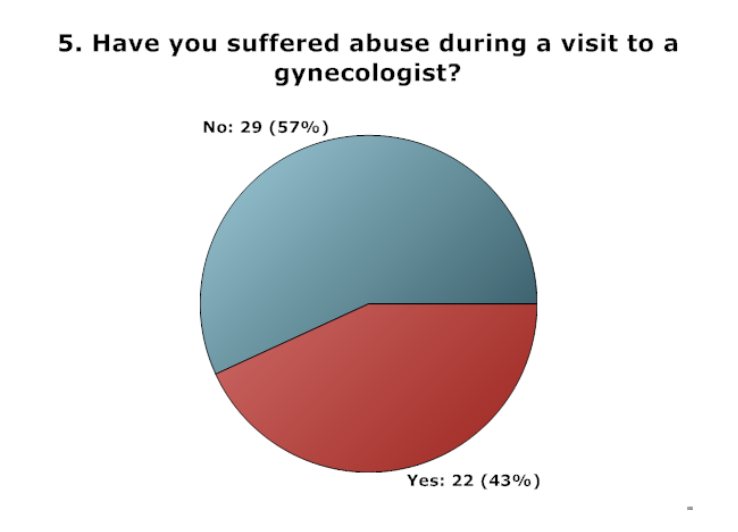

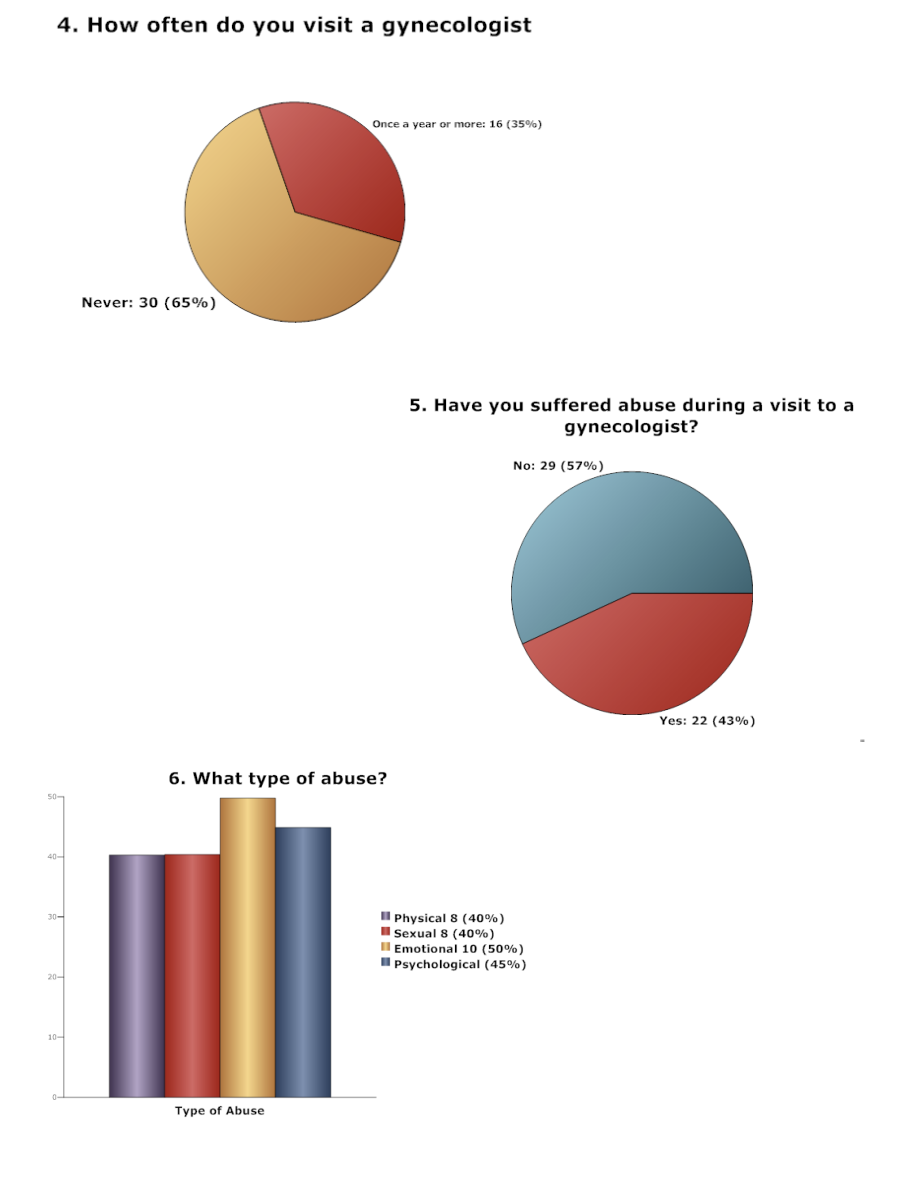

The main reason the women gave for not going to a gynecologist was high rates of abuse. Our findings are extremely disturbing: 43 percent of the women that were interviewed stated that they had been mistreated/and or suffered abuse while visiting a gynecologist (see Chart 5 below).

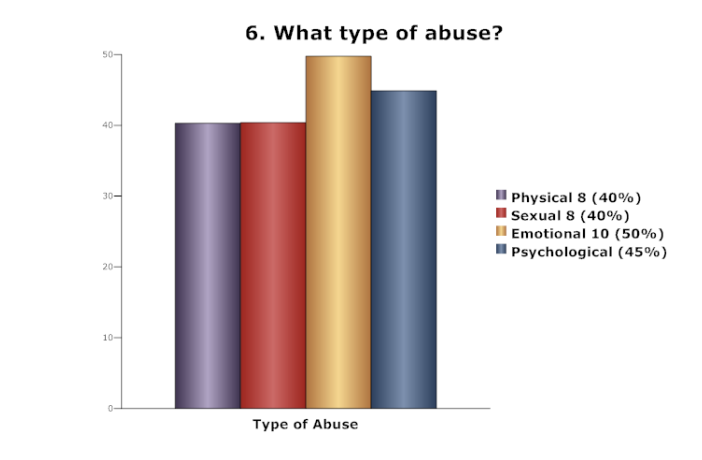

The 22 women who had experienced mistreatment were then asked what abuse they had experienced. Of the 20 who responded, 40 percent reported that they suffered sexual abuse including rape; 40 percent indicated that they had suffered physical abuse; 50 percent that they had suffered emotional abuse; and 45 percent suffered psychological abuse (see Chart 6 below). 74

Our finding that more than 40 percent of the participants have been subjected to some form of abuse from a medical professional appears to shows that this is a generalized problem and evidences the inability or lack of will of the Mexican government to guarantee safe access to sexual and reproductive health services. This failure is a breach of Article 25 of the CRPD. As a result of the high rate of sexual abuse,75 women with disabilities are more likely to experience anxiety and re-victimization when dealing with sexual and reproductive health care providers, often causing them to avoid health services altogether, which puts them at higher risk of undiagnosed health problems76 . The CRPD Committee urged the Mexican government to “ensure that the right to sexual and reproductive health services is available to women with disabilities in an accessible and safe manner”. 77 It should also be noted that this finding is a direct violation of Article 16 of the CRPD, which outlines the State’s responsibilities to ensure that people with disabilities are free from gender-based exploitation, violence and abuse, and given the impunity in which these abuses remain, of Article 14, which guarantees women with disabilities access to justice.78

Women are not only prevented from visiting a gynecologist by their fear of abuse; we also found that family members, health authorities, and doctors deny access to women with disabilities to visit a gynecologist on the basis of their disability. Of the 12 participants that had been denied access, six said that they had been denied access by either medical staff (4 participants) and or their own family members (2 participants) (Annex I, chart 2).

It is urgent that Mexico take measures to guarantee safe access to sexual and reproductive health services to women with disabilities, on an equal footing with others, so they can make informed decisions. Mexico must also take immediate action to prevent, investigate, and punish abuses against women with disabilities seeking access to gynecological services. Finally, the government should guarantee that no woman is prevented from seeing a specialist on sexual and reproductive health, in accordance with the recommendations made by the CRPD Committee and as established by the Convention itself.

3. Forced sterilization and contraception

The CRPD Committee has affirmed in several concluding observations that forced treatment by psychiatric and other health and medical professionals is a violation of the right to personal integrity (Article 17); freedom from torture (Article 15); and freedom from violence, exploitation and abuse (Article 16).79 This practice also denies the right of the person to choose medical treatment and is therefore also a violation of Article 12 of the Convention (equality before the law). The Committee recognizes forced treatment, including forced and coerced sterilization and contraception, as a particular problem for persons with psychosocial, intellectual and other cognitive disabilities80 . Forced and coerced sterilization and contraception usage also constitutes a violation of Article 23, clause 1, subparagraph b) which states that “persons with disabilities, including children, retain their fertility on an equal basis with others”.

a. Forced sterilization as torture

“All of the girls have to be sterilized.” –Director of an institution that houses children with mental disabilities.

“My family forced me to be sterilized.” -Woman with a psychosocial disability

One of the greatest concerns for women and girls with disabilities is the practice of uninformed, nonconsensual, forced or coerced administration of contraception and sterilization performed under the auspices of necessary medical care.81 There is a tendency to deny women with disabilities their right to motherhood82 and as a result women and girls with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to forced and coerced sterilization and contraception. According to the CRPD Committee, “women with disabilities are subjected to high rates of forced sterilization, and are often denied control of their reproductive health and decision-making, the assumption being that they are not capable of consenting to sex”. 83

Forced sterilization occurs when an individual is sterilized after expressly refusing the procedure, without her knowledge, or is not given an opportunity to consent. Coerced sterilization is when financial or other incentives, misinformation, or intimidation tactics are used to compel an individual to undergo the procedure.84 In 2013 the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture concluded that forced sterilization of people with disabilities violates the absolute prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.85 In Mexico, women and girls with psychosocial disabilities are at a high risk of being sterilized without their consent, at the request of their parents or guardians. 86 Since 1985, the records of the Directorate-General on Special Education in Mexico have shown that there is a “marked interest of parents on sexual issues related with the possibility of sterilizing their children”. 87

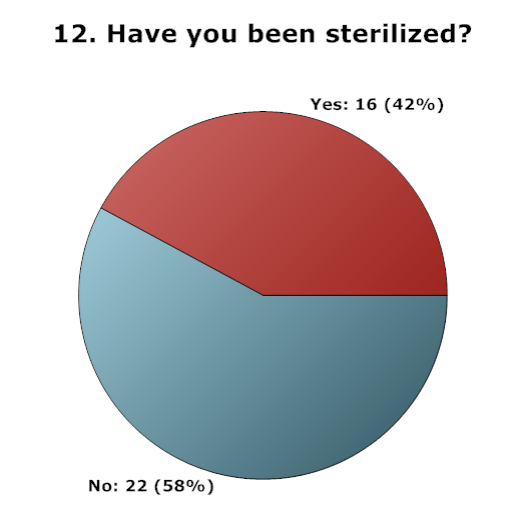

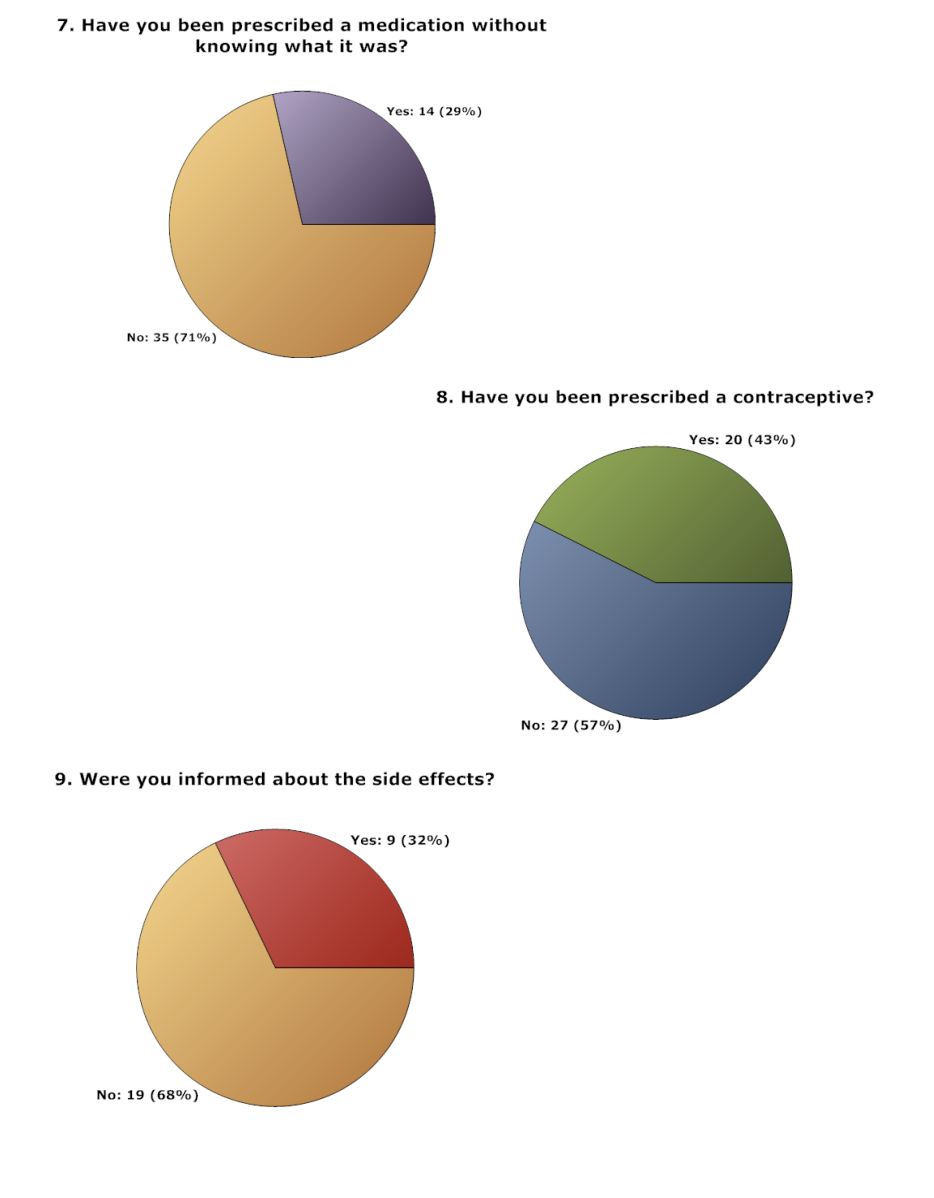

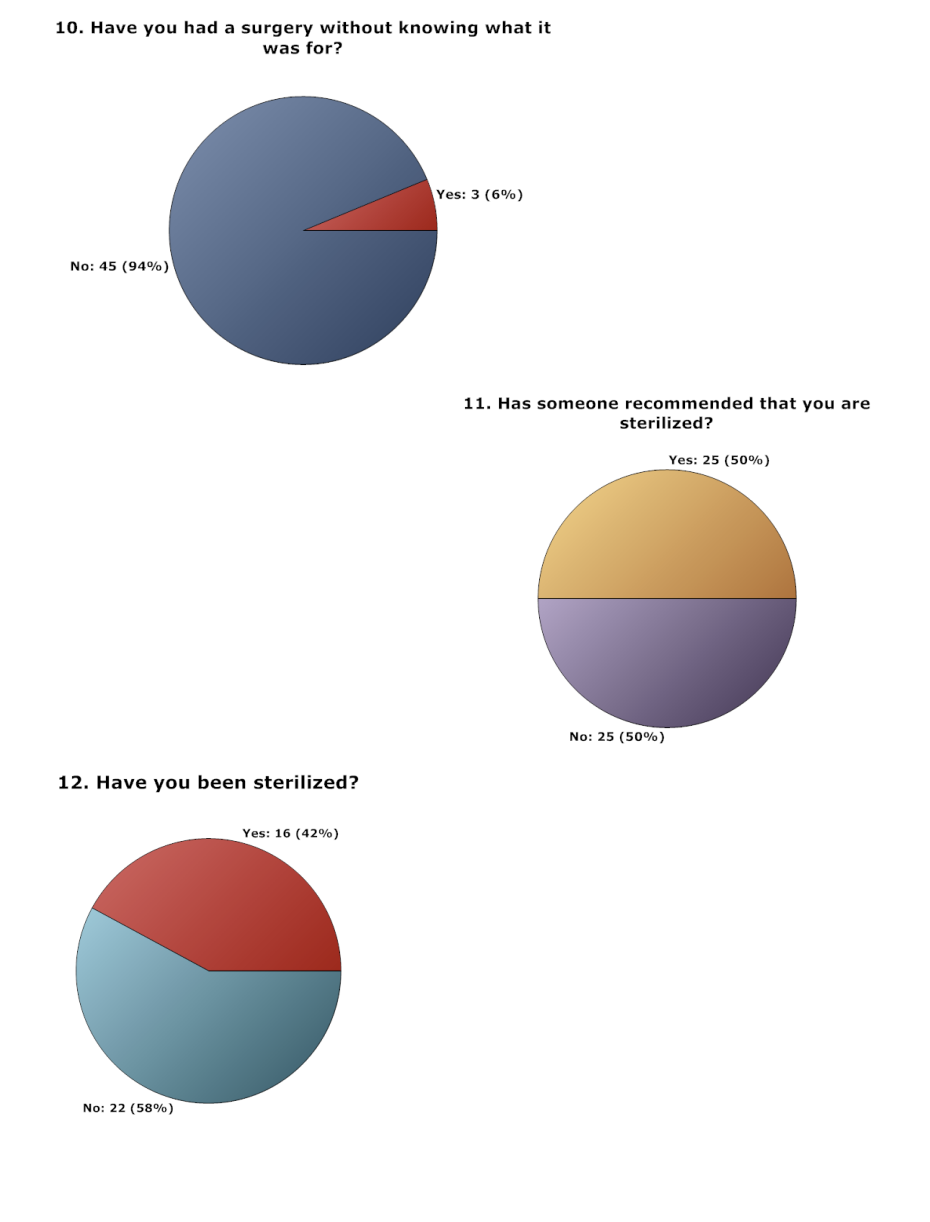

The results of our study are shocking: one in two women were recommended sterilization by a family member or by medical staff (Annex I, chart 11) and 42 percent of the women that answered the question had actually been sterilized (see chart 12 below).

The main reasons given by family members or medical staff to sterilize women is that they have a disability and that the child can inherit the disability (see Section III.1). One woman, with tears in her eyes, told us that she did not want to be sterilized but the pressure from her family was too strong. She deeply wanted to be a mother but instead she ‘would have to settle for taking care of her nieces’ – the consolation given by her family.

Particularly shocking are the cases of three women who reported that they had had a surgery but had not been informed what it was for. However, in a body diagram that we provided for them to indicate where they had had the surgery, they pointed to the female reproductive organs. We suspect these women were sterilized without even knowing it.

It is should be noted that not being sterilized is not a guarantee that a women will be allowed to start a family. One of the women we interviewed told us, “I have not been sterilized but I have not been allowed to have children.”

According to Human Rights Watch (2011), the practice of sterilization continues to be justified by many governments, legal, medical, and other professionals and family members and carers as being in the “best interests” of women and girls with disabilities. These “interests” often have little to do with the rights of women and girls with disabilities and more to do with social factors, such as avoiding inconvenience to caregivers, the lack of adequate measures to protect against sexual abuse and exploitation, and the shortage of suitable services for mothers with disabilities.88

It is widely accepted that girls and women with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse.89 Instead of seeking to prevent the abuse, health professionals and guardians have traditionally viewed forced sterilization and contraception as effective methods to ‘protect’ women from pregnancy in case they are raped. 90 In 2002, Inmujeres documented the sterilization of women with disabilities at the request of their parents to avoid pregnancy in cases of sexual abuse.91 In our research we also encountered a woman who was told by her family that she was going to be sterilized to “protect her from sexual abuse”. Rather than protecting a woman with a disability against sexual abuse, forced sterilization can often increase her vulnerability to sexual abuse.92

DRI has also documented forced sterilization of girls and women with disabilities in institutions. In 2015 DRI visited an institution for children with disabilities referred by the Ministries for the Development and Integration of Families (DIF) of states outside Mexico City. When we asked the director about contraceptives administered to the girls, he replied that it is not necessary “because most of them have been sterilized”. Some of them were sterilized by the DIF before it referred them to the institution and some were sterilized by their own families. According to the director, the institution itself does not have the legal authorization to sterilize the girls so they are currently “seeking the authorization of the DIF or of the families to sterilize the remaining girls who have not yet undergone the surgical procedure” because “all of the girls have to be sterilized.” A care worker that has been to the institution told DRI that a girl inside said that there was sexual abuse at the facility and that she was raped almost every day. This is consistent with DRI’s findings of generalized sexual abuse in most institutions that shelter children and adults with disabilities. Girls inside this institution are being forcefully sterilized to avoid pregnancies that are the result of rape.

Likewise, a medical professional from the Psychiatric Hospital ‘Fray Bernardino’ stated that, even though the opinion of women with disabilities must be taken into account, in the Mexican health system it is common that these women are sterilized without their consent. According to this professional, the parents usually ask that the sterilization procedure is performed, but there are also doctors who order these procedures.

b. Uninformed and forced administration of contraceptives

“I want to be taken into account.” -Woman with a psychosocial disability

Additionally, Mexico has violated its obligation to provide sexual and reproductive health care that is based on informed consent. Through our research we found that more than 40 percent of the women interviewed have been prescribed contraceptives (Annex I, chart 8) and the large majority of them (68%) were not informed about alternatives or the side effects (Annex I, chart 9). Almost 30 percent of the women reported that they had been given prescriptions without knowing what medications they were taking (Annex I, chart 7). For every one in two women that had been prescribed contraceptives, their family, a doctor, or a psychiatric institution made the decision, which may constitute a type of coerced contraception.

Women with disabilities who are institutionalized are more likely to be prescribed long-acting, injectable contraceptives and are usually excluded from the decision-making process.93 DRI has documented this practice in institutions in Mexico and Guatemala, where there are high rates of sexual abuse, especially against women.94 It should be noted that forced contraception has also been recognized as a form of torture under international human rights law.95

By allowing the forceful and coerced sterilization of girls and women with disabilities, particularly in institutions under the direct authority of the government, Mexico is violating their right to respect their physical and mental integrity (Article 17); their right to retain their fertility on an equal basis to others (Article 23); to be free from violence, exploitation and abuse (Article 16); and to decide for themselves (Article 12), all of which are enshrined in the CRPD. It is imperative that Mexico adopts measures to prevent, punish and eradicate the practice of forced and coerced sterilization of women with psychosocial disabilities.

4. Lack of access and discrimination against mothers with disabilities

a. Pressure to have an abortion and give a child up for adoption

Due to inaccessibility, lack of information, insensitive treatment, and the assumption that they are not sexually active, women with disabilities often lack essential reproductive and obstetrical care. Women with disabilities who have little or no knowledge about sexual and reproductive health are more often than not coerced into decisions they cannot freely make. 96 Pregnant women are at a particular risk of being forced or coerced into having an abortion, especially when there is ‘fear’ that her disability will be passed on to her child, 97 because “medical discourse has at its core belief that if there is a risk of abnormality, or a risk of worsening an already abnormal bodily condition, then steps must be taken to avoid it.” 98

Almost thirty percent of the women who had been pregnant stated that they were told to abort the child. One woman told us that she was forced by her family to have an abortion because she was unable “to take care of the child.” Women with psychosocial disabilities are particularly vulnerable of being forced to have an abortion if they seek maternal care during a psychiatric crisis. A mother with a psychosocial disability told us:

“When I was pregnant I wanted to stop the medications so that it would not affect my baby. However, this caused me to have a psychiatric crisis. I went to a psychiatric consultation and the doctor told my mom that I had to have an abortion, like it was routinely done. The doctor and my mother were having this conversation while I was there but they never asked me directly what I wanted to do, they completely ignored me. It was as if I was there but I was not there, the baby was inside me but for the two of them was as if it was only a bump over which they had to make a decision: that it had to be aborted. I was four months pregnant. They referred me to the obstetrics unit to have the abortion carried out then and there. The psychiatrist made me feel terrible; it seems as if for the doctors, women with disabilities are objects without any will or desire. It did not matter that it was my body and my baby, they thought they could decide for me.

In the obstetrics unit, a gynecologist did the ultrasound. I told her that I did not want to abort and I begged her to stop them from taking my baby away from me. She promised me that she would not allow it. If it wasn’t for her, most likely I would not have my beautiful daughter with me today.”

For women with disabilities who are pregnant, seeking care and giving birth becomes a very difficult and even traumatic experience. Discriminatory practices and the fear of being forced to have an abortion prevent women with disabilities from accessing maternal health care. Particularly worrying is the fact that forced and coerced abortion is encouraged and practiced by the health sector, and is therefore the direct responsibility of the government. The CRPD Committee recommended that Mexican authorities investigate and take punitive action against medical staff who pressure pregnant women with disabilities to abort.99

b. Lack of access to health and reproductive services

When I became pregnant, they refused to provide me care at a social security clinic. I had to cover the costs of my pregnancy at a private clinic. –Woman with a psychosocial disability.

Women with disabilities who are not forced to abort will likely be denied access to adequate and affordable obstetrical care. Disability has a strong correlation with poverty, which means that the majority of women with disabilities are likely to rely on social security. In Mexico, social security will not cover maternity care for women with disabilities, leaving them virtually unprotected before, during, and after birth. The medical sector often views women with disabilities who become pregnant as irresponsible (see Section III.1), leading them to determine that the problem is strictly their own and not that of society or the public health services.100

The 2010 Inmujeres report documented that mothers with disabilities were mostly cared for by private doctors. 101 In our research, one mother told us that her social security policy automatically removed pregnancy related costs because of her disability. When she became pregnant, she was denied care at the social security clinic and had her baby in a private hospital where costs are extremely elevated.

Another mother we interviewed told us that after being denied maternal health care at a public clinic, she would have to seek private treatment. This is in clear violation of subparagraph a) of Article 25 of the CRPD which requires States to “provide persons with disabilities with the same range, quality and standard of free or affordable health care and programs as provided to other persons, including in the area of sexual and reproductive health […]”.

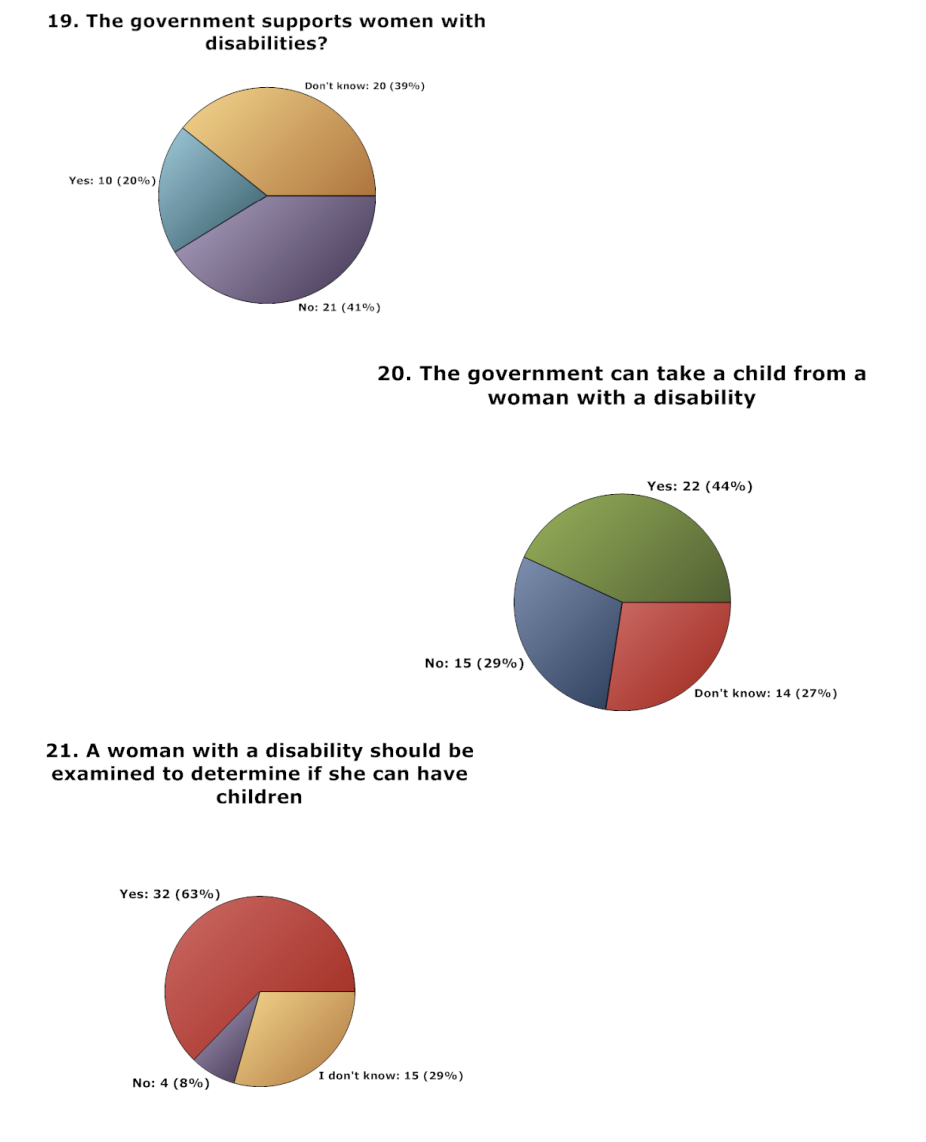

c. Lack of support for mothers with disabilities

The second clause of Article 23 establishes that “States Parties shall render appropriate assistance to persons with disabilities in the performance of their child-rearing responsibilities”. Mexico has failed to uphold this obligation. More than 40 percent of the women interviewed stated that the government did not provide support for mothers with disabilities (Annex 1, chart 19). Out of the 19 women that were interviewed and had children, three women gave their children up for adoption, eight stated they took care of their children on their own, five said that they took care of their children with help from their family, and another five women stated that their children were taken away by a family member, by the father, or by the father’s family. For mothers with disabilities who raise their children on their own or with the help of family members, it often becomes an extremely difficult and sometimes even painful experience. According to one of the mothers we interviewed:

“For me it was very hard to raise my child. To date I do not know how I managed. I used to sleep a lot, I had severe depression. When my son would cry I would get up to take care of him. They took me to many psychologists but all of them would laugh at me. I did not receive any support to raise my child; neither did I receive mental health support when I requested it. There is no support for us mothers with disabilities. There must be some support for mothers with disabilities, including economic support and workshops on maternity and disability.”

Governments need to tackle the barriers and discrimination that women face in virtually all sectors of society, particularly in the medical and labor sector. Discrimination that leads to a lack of opportunities often means that women cannot live independent lives and will not be able to raise their children on their own. One woman we interviewed, who became pregnant as the result of sexual abuse, developed a psychosocial disability because of the traumatic experience. She told us, “after my pregnancy I was fired from my job because people heard that I had become schizophrenic. They would not allow me to enter the office after that and I was also denied other job opportunities.” She still had to raise her child on her own without any support from the government, despite being unemployed.

Furthermore, more than 40 percent of the women with disabilities believed that a woman with a disability can have her child taken away by the authorities (Annex I, chart 20). This fear, compounded by lack of support, prevents mothers from obtaining the care they need, even when it is crucial for them to be able to raise and keep their child. It is essential that the government creates accessible programs to support women with disabilities in order to prevent the separation of children from their mothers (in accordance with Article 23 of the CRPD). This is particularly important because there is no alternative care or effective foster care system in Mexico. Children that are separated from their parents are likely to end up in an institution, therefore perpetuating a cycle of violence, poverty, and segregation. In this regard, the CRPD Committee recommended that the government establish programs to provide adequate support for mothers with psychosocial disabilities to assist them in their child-rearing responsibilities and establish mechanisms to support families.

5. Women with disabilities do not know their rights

There is a profound lack of information among women with disabilities about their own rights. Seventeen out of 48 women (35%) reported that they knew their rights under the CRPD. However, it should be noted that seven of those women belonged to the Colectivo Chuhcan and have received intensive training on their rights recognized by the CRPD. The 2002 Inmujeres report confirms our findings. 102 In this regard, we strongly recommend the government to implement programs to train women with disabilities on their rights and to empower them to advocate on their own behalf and on behalf of other women with disabilities in similar situations.

IV. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Mexico still has a long way to go toward guaranteeing the rights of persons with disabilities, particularly their sexual and reproductive rights. For women with disabilities, the grave violations that we uncovered are in direct violation of their rights to a home and family (Article 23); to protection of their physical and mental integrity (Article 17); to freedom from violence, exploitation and abuse (Article 16); and to equality before the law, including their right to legal capacity (Article 12), recognized in the CRPD. Given our findings, we recommend that Mexico:

- Amend its legislation to conform with international standards on the right to legal capacity of persons with disabilities. In particular, Mexico City must amend the Civil Code Articles that prevent persons with disabilities from getting married and that establish that a married person that develops a psychosocial disability must be placed under the guardianship of his/her spouse and lose any say in the upbringing of his/her children.

- Develop programs that address the stereotypes and myths regarding women with disabilities and educate and sensitize society on the rights of this group. These programs must also be specifically designed to empower women with disabilities through learning about their rights. These programs must have a sexual and reproductive health component, in accordance with Article 25 of the CRPD.

- Guarantee that women with psychosocial disabilities have access to safe sexual and reproductive services and address the alarmingly high rate of abuse against women with psychosocial disabilities that seek this type of service. Mexico must also investigate these abuses and violations and bring those responsible to justice.

- Ensure that pregnant women with psychosocial disabilities have access to public maternal care services. Mexico must also investigate, punish, and prevent medical personnel who pressure pregnant women with disabilities to have abortions, especially in cases where the abortion is actually performed.

- Create programs to provide adequate supports to mothers with psychosocial disabilities to assist them in their child-rearing responsibilities. It is particularly important for the government to design programs that prevent separation of women with disabilities from their children.

- Put an immediate end to forced and coerced sterilization of women with psychosocial disabilities. The high rate of forced and coerced sterilization is extremely concerning. The Mexican government must investigate and punish cases of forced and coerced sterilization. It must also ensure access to justice for women with psychosocial disabilities that have been forced or coerced to undergo this procedure. Mexico must also take immediate steps to prevent this violation from happening again.

- Urgently investigate violations against the sexual and reproductive rights of women in institutions and the situation of the sexual and reproductive rights of women with psychosocial disabilities in Mexico.

- Create deinstitutionalization programs for women and girls with disabilities, in accordance with the Concluding Observations made by the UN CRPD Committee.

ANNEX I. RESEARCH RESULTS

ANNEX II. SURVEY ON THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN WITH DISABILITIES

Thank you for taking part in this questionnaire. This questionnaire is about sexual and reproductive rights for women with disabilities. Our goal is to find out more about the situation of these rights for women in Mexico. Please note that there is no right or wrong answer and that if you do not wish to answer one of the questions, you do not have to. Lastly, we will ensure that your anonymity is maintained at all times.

I. Personal Information

Studies: Secondary School High School University

II. Sexual/Reproductive Education and Professional Medical Support

1) How much do you know about sexual and reproductive health? (Please circle the most appropriate answer)

A lot

A little

Nothing

2) Please circle as many options as are applicable to you. I learned about sexual and reproductive health and rights from:

My family

My friends

My partner

A doctor

My own research (for example on the Internet, in books, at church)

The media (for example movies, music, posters, television)

Other (please specify) _____________________________

Nobody. I do not know about women’s sexual and reproductive health.

3) Would you like to know more about sexual and reproductive health?

Yes. Please specify what type of information you would like to have________ _______________________________________________________________

No

4) A gynecologist is a doctor who specializes in women’s sexual and reproductive health. How often do you visit a gynecologist?

Multiple times a year

Once a year

Once every few years

Never

4a) If you answered that you visit a gynecologist frequently (multiple times a year or once a year), could you please circle the option that applies the most to your consultations:

The gynecologist talks to me and uses words I understand.

The gynecologist talks to me but uses words I don’t understand.

The gynecologist talks to my support person or guardian.

4b) If you have never been to a gynecologist or do not visit one regularly, could you please tell circle the option that best applies to your reasons not to do it:

I do not want to visit a gynecologist. Could you tell us why? ______________________________________ _________________________________________________________

I have never had the option to visit a gynecologist

I am not allowed to visit a gynecologist. Could you tell us why? ______________________________________ _________________________________________________________

Other (please specify) __________________________

5) Have you ever wanted to visit a gynecologist but have been denied access?

Yes

No

5a) If you answered yes to question 5, could you please tell us who denied you access and why you were denied access? If you answered no, please go to question 6.

I was denied access by: _____________________________

I was told I was denied access because: _______________________________ _______________________________________________________________

I think I was denied access because: _________________________________ _______________________________________________________________

I don’t know why I was denied access.

6) Have you ever been mistreated while visiting a gynecologist or a general doctor?

Yes

No

6a) If you answered yes to question 5, what type of mistreatment did you receive? If you answered no, please go to question 6.

Physical mistreatment

Sexual mistreatment

Emotional mistreatment

Psychological mistreatment

Other (please specify) _______________________________

6b) If you want to, could you please tell us more about what happened?

Yes: ___________________________________________________________

No (I prefer not to answer)

III. Use of pregnancy prevention methods

7) Have you ever been prescribed a medication that you didn’t know what it was?

Yes

No

8) Have you ever been prescribed a medicine that prevents pregnancy (such as the Pill, Depo Provera etc.), also known as a contraceptive?

Yes

No

8a) If you answered yes to question 8, who made the decision to prescribe you a contraceptive? If you answered no, please go to question 9.

Myself

My family

A psychiatric institution

A doctor

Other (please specify) ___________________________

8b) Were you informed about the alternatives, risks, benefits and side effects of the prescribed medicine?

Yes

No

8c) For what reasons do you think a woman with a disability might be prescribed a contraceptive? Please circle all the answers that you think are applicable.

Because she is sexually active and wishes to avoid pregnancy

Because her doctor, partner, guardian or family thinks it is for the best

For health reasons other than pregnancy prevention

Other (please specify) _____________________________________________

9) Have you ever undergone a surgical procedure that you did not know what it was?

Yes

No

9a) If you answered yes to question 9, please indicate where you had the surgery on the image below: (a picture of woman’s silhouette will be shown)

10) Have you ever been recommended a surgical procedure of sterilization?

Yes

No

10a) If you answered yes to question 10, who recommended the procedure? If you answered no, please go to question 11.

My family

A psychiatric institution

A doctor

Other (please specify) ___________________________________

10b) What reasons were you given for this recommendation? _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________

10c) Have you undergone a procedure of sterilization?

Yes. ¿Could you tell us what happened? ______________________________ _______________________________________________________________

No

10d) Whose decision was it? ___________________________________

III. Right to Motherhood

11) Do you have children?

Yes

No

11a) If you answered yes to question 11, who takes care of the children? If you answered no, please go to question 12.

I take care of them on my own

I take care of them with the support of my family/partner

My family/partner takes care of them

The child has been given for adoption

Other (please specify) ___________________________________

12) If you have been pregnant, has anyone recommended you not to have the child or to give it in adoption?

Yes

No

12a) If you answered yes to question 12, why did they say it was best not to have the child? If you answered no, please go to question 13.