Left Behind:

The Exclusion of Children and Adults with Disabilities from Reform and Rights Protection in the Republic of Georgia

Primary Author:

Eric Mathews, Advocacy Associate, Disability Rights International (DRI)

Co-Authors:

Laurie Ahern, President, DRI

Eric Rosenthal, JD, Executive Director, DRI

James Conroy, Ph.D., Center for Outcome Analysis

Lawrence C. Kaplan, MD, ScM, Division Chief of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Baystate Children's Hospital

Robert M. Levy, JD, Adjunct Professor of Law, Columbia University Law School

Karen Green McGowan, RN, President-Elect of the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association

Funded by:

The Open Society Foundations,

The Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation,

The Morton and Jane Blaustein Foundation,

and other generous foundation and individual supporters of DRI

Contents

- Preface: Goals and Methods of this Report

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Summary of Recommendations

- I. Introduction: Political and Social Context of Reforms

- II. Observations

- A. Denial of Medical Care for Children with Disabilities

- The Tbilisi Infant Home

- The Senaki Orphanage for Children with Disabilities

- B. Segregation and Abuse of Children and Adults with Disabilities

- Community Services Discriminate Against Children with Disabilities in Institutions

- Abandonment of Adults with Disabilities

- Denial of Legal Personhood and Access to Justice

- Insufficient Oversight and Monitoring

- A. Denial of Medical Care for Children with Disabilities

- III. Human Rights Obligations and Strategic Recommendations

- IV. Recommendations to International Donors

- V. Appendix A: Clinical Evaluation by Dr. Lawrence Kaplan

- VI. Endnotes

Preface: Goals and Methods of this Report

One billion people with disabilities around the world are disproportionally represented among the world’s poor, and are widely subject to stigma and discrimination.[1] Over twenty years, Disability Rights International (DRI) has documented the most extreme abuses against people with disabilities that take place where people are segregated from society: in orphanages, psychiatric facilities, nursing homes, and “social care” facilities (see our reports at www.DRIadvocacy.org).

The recent adoption and widespread ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) brings needed attention to important human rights protections of a population long overlooked by the human rights community. Article 19 of the CRPD establishes that all persons with disabilities have a right to live in the community. Although 138 countries have ratified the CRPD[2] , most countries still segregate children and adults with disabilities. According to UNICEF, there are at least 8 million children in institutions around the world.[3] The actual number may be much larger, as DRI has found children detained off the public record in many countries. There is no accounting for the vast number of children who die in institutions without ever being counted or noticed – or for children who grow up and languish in adult institutions for a lifetime.

This report documents policies and practices of the Republic of Georgia to examine the protection of rights of the country’s most vulnerable population: children with disabilities who are detained in institutions. While we examine rights abuses within institutions, such as life-threatening practices, inhuman and degrading treatment, and torture, our experience has shown that the protection of rights ultimately depends on the enforcement of CRPD article 19. Until all children have the opportunity to live in the community with the love and protection of a family, their rights cannot be fully enforced.

DRI’s broader strategic goal is to bring an end to the segregation of people with disabilities worldwide as required by CRPD article 19. This report is part of our Worldwide Campaign to End Institutionalization of Children. Through this campaign, we are demonstrating the dangers of placing any child in an institution – a practice that creates disability, kills children at an alarming rate, and leads to life-time segregation for millions of people with disabilities.[4] Children are abandoned to institutions due to poverty, disability, or being part of a devalued minority.[5] We are partnering with activists across the globe to fight for the world’s most marginalized people.

DRI’s Worldwide Campaign to End Institutionalization of Children is also intended to help donors and international development agencies develop programs that comply with the CRPD and effectively promote the right to community integration. It is our hope that this report will assist in the international effort to protect and serve people with disabilities in Georgia. The CRPD includes an innovative provision, article 32, requiring international donors to promote the “purpose and objectives” of the convention and to ensure that development programs are “inclusive of and accessible to persons with disabilities.” While governments bear the ultimate responsibility for the protection of human rights, donors can and must also be held accountable to the principles of the CRPD.

This report is the product of extensive fact-finding efforts, in collaboration with a broad array of local government and non-governmental organizations in Georgia, as well as legal, medical, and disability experts from abroad. From July 2010 through September 2013, DRI conducted 6 fact-finding visits to the Republic of Georgia. DRI examined conditions in 10 residential institutions including all state-run baby houses and orphanages for children with disabilities, four social care homes for adults with disabilities and a boarding school for children with disabilities. This report does not examine Georgia’s psychiatric hospitals.

DRI engaged the volunteer expertise of a high level group of experts, including: James Conroy, Ph.D., of the Center for Outcome Analysis; Lawrence C. Kaplan, MD, ScM, Division Chief of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at the Baystate Children's Hospital; Robert M. Levy, JD, Adjunct Professor of Law at Columbia University Law School; and Karen Green McGowan, RN, President-Elect of the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association.

This report is not intended to place blame on any individuals, policy-makers, or institution staff. We recognize that both governmental authorities and international advisors have intended to do what is best for children and adults with disabilities. Many members of institutional staff we encountered work under the most difficult of circumstances and could not continue to work except out of their professional dedication and care for the individuals they serve. DRI would like to thank the many public officials, professionals and staff who contributed their time and insight to our work.

In every institution we visited, we attempted to be as thorough as we could in understanding the human rights situation of people living in the facility—in many cases, returning to the institution several times. We asked to visit all parts of the institutions. We interviewed institutional authorities, staff and residents. During each site visit, DRI brought a video camera to record observations. We took photographs in each institution. It is our experience that photo and video documentation is tremendously helpful in corroborating our observations and helping the public to understand the reality of life in an institution. We are sensitive to the concerns of individuals depicted in the photographs, for whom placement in an institution may constitute a massive violation of their privacy and their ability to make choices about their lives. We generally find that people within institutions are amenable or eager to have their photographs taken.

DRI visited the following institutions:

- Tbilisi Infant Home (5 visits)

- Makhinjauri Infant Home (1 visit)

- Kodjori Orphanage for Children with Disabilities (3 visits)

- Senaki Orphanage for Children with Disabilities (2 visits)

- Tbilisi Boarding School #200 for Children with Disabilities (1 visit)

- Martkopi Social Care Home for Adults with Disabilities (2 visits)

- Dzevri Social Care Home for Adults with Disabilities (1 visit)

- Temi Home for Adults with Disabilities (1 visit)

- Qedeli Home for Adults with Disabilities (1 visit)

- Gldani Psychiatric Hospital (2 visits)

There is no doubt that there are valuable programs — as well as serious abuses — that we were not able to include in our report. In recent years, numerous model programs have been established to provide support to people with disabilities in the community, particularly family support and early intervention programs designed to prevent institutionalization. It is our hope that this report will support the extension of these programs to include all institutionalized persons with disabilities.

This report issues recommendations to the Government of Georgia and to development agencies based on international standards consistent with the UN CRPD to ensure that children and adults with disabilities are afforded their human right to live full and meaningful lives, in a family, in the community.

In addition to our investigation, Disability Rights International (DRI) has worked with local activists and government officials in the Republic of Georgia since 2010 to actively protect the human rights and promote the full community integration of children and adults with disabilities in the country. As a result of our advocacy and collaboration with local partners, some of the most egregious human rights abuses facing people with disabilities that we observed in Georgia have already been addressed – in advance of this release of this report:

- Children’s lives have been saved by reducing the arbitrary and discriminatory denial of medical care to children with disabilities - As a result of DRI’s sustained advocacy in cooperation with local organization Children of Georgia and the Georgia Public Defender’s Office, children with disabilities in Tbilisi Infant’s House who were being discriminatorily denied medical care were given life-saving treatments. As this report describes, however, the denial of appropriate care remains a challenge and urgent action is still needed to protect children with disabilities.

- DRI contributed expert medical and legal support to the Georgia Public Defender’s Office in 2012 to investigate and publish a powerful and well-documented report on torture and ill-treatment within Georgia’s state-run institutions for persons with disabilities.[6]

- Plans to create small new institutions have been modified to create group homes - In 2011, DRI learned of plans being developed by a major international donor to create 14-bed facilities for children with disabilities.[7] Following a 2012 training by DRI of Georgian activists and government officials, the donor reversed its plans and the government agreed to no more than 6 residents for any future community-based residential services for children with disabilities. This “less is more” approach has been dubbed by some local activists as “the DRI model.” We should note, however, that DRI is in favor of the most integrated settings and support even smaller homes or family placements as the best model.

- The US Congress has condemned US government practices of rebuilding institutions - After DRI presented its documentation of USAID and Department of Defense funding to build and renovate segregated institutions for persons with disabilities in Georgia, the US Senate Committee on Appropriations condemned the use of USAID funds which “resulted in the improper segregation of children and adults with disabilities during a period in which the iv Government of Georgia adopted a policy of deinstitutionalization for children.” The Committee further directed the US Agency on International Development to develop and implement a plan for the community integration of children and adults with disabilities who are in institutional settings. While USAID has funded a number of valuable disability projects, including family support programs and foster care, the US government has not, to our knowledge, taken action to integrate persons into the community who live in institutions rebuilt with US government funds.

This report was originally written in English. While we have made every effort to provide an accurate translation, there are inevitably differences in technical meaning or nuance. If there is any question about a discrepancy between the two versions, please refer to the English original.

Acknowledgements

Disability Rights International (DRI) is indebted to the many individuals and organizations who volunteered their time and energy to provide insights on the human rights situation of persons with disabilities in the Republic of Georgia.

EveryChild of Georgia, The Georgia Public Defender’s Office, Children of Georgia, First Step of Georgia, UNICEF and the US Agency for International Development were particularly generous with their time.

DRI is appreciative to have learned from the lived experience of Georgia’s disabled person organizations (DPOs). Advocates we met from the Partnership for Equal Rights, the Georgia Coalition for Independent Living, and An Accessible Environment for Everyone were truly inspiring.

We would like to thank the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs for allowing us access to institutions for this investigation. We would like to thank Giorgi Kakachia in particular for his blunt and honest assessment of Georgia’s challenges, and his obvious compassion for children and adults with disabilities in institutions.

We would like to thank Bruce Curtis, World Institute on Disability, for inviting us to Georgia and introducing us to disability activists in the country.

On every trip, we had the fantastic experience of being driven by Zviad Pirtskhalava.

None of DRI’s work is possible without the support of Adrienne Jones, our Director of Finance and Administration, and her assistant S. Sinclair. We are additionally grateful for the work of Julia Wolhandler, our Development Associate, in reviewing and editing the citations of this report.

We wish to express our gratitude to the Open Society Foundations, the Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation, the Morton and Jane Blaustein Foundation, and other foundation and individual supporters who believe in our mission and make our advocacy possible.

And a very special thanks to Anna Arganashvili, Ana Lagidze, Ana Abashidze, and Andro Dadiani for their assistance and deep personal commitment to the rights of people with disabilities.

Executive Summary

Left Behind: The Exclusion of Children and Adults with Disabilities from Reform and Rights Protection in the Republic of Georgia is the product of a 3-year investigation by Disability Rights International (DRI) into the orphanages, adult social care homes and other institutions that house children and adults with disabilities in the Republic of Georgia.

This report documents violations of the human rights of persons with disabilities in the Republic of Georgia under international human rights treaties ratified by Georgia, including the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child[8], the European Convention on Human Rights[9], and the UN Convention against Torture[10], as well as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,[11] which Georgia has signed.

The report documents the exclusion of children and adults with disabilities from domestic reforms and international development agendas. Over the past decade, the Government of Georgia has undertaken an ambitious child care reform process. As a result, the majority of its state-run institutions for children without disabilities have been closed and replaced with community services which enable vulnerable families to keep their children at home. The positive results of these efforts are extensive and credit should be given to the government and its partners for these achievements. UNICEF has played an important and valuable leadership role in planning these reforms. DRI’s investigation found, however, that institutionalized children with disabilities were largely excluded from this reform process. These children continue to be marginalized and abused. Without services for adults with disabilities, these children face the prospect of life-long segregation from society.

A parallel system of orphanages exists under the authority of the Georgian Orthodox Church. While the government is shutting down state-run orphanages, it continues to fund the establishment of new orphanages run by the church. Because these facilities are completely unregulated, they create particularly serious risks to human rights. The exact numbers of children in these facilities are off the public record.

The exclusion of many children and adults with and without disabilities from reforms has permitted life-threatening abuse, neglect and segregation to continue in Georgia’s orphanages and other institutions. Even while the Republic of Georgia was closing state-run institutions for children without disabilities, the United States government and other international organizations provided funding for the building or renovation of new institutions for persons with disabilities—perpetuating segregated care for Georgia’s most vulnerable population. These actions have not advanced the principles of human rights promoted by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Within Georgia’s residential institutions, children with disabilities are subjected to physical and emotional neglect and abuse, and many children are denied life-saving medical treatment simply because they have a disability. In one orphanage, DRI documented a 30% death rate for children with disabilities over an 18-month period in 2009-2010. Those who survive to adulthood are warehoused indefinitely.

In institutions DRI visited in Georgia, investigators witnessed children and adults who spend their lives in inactivity, some rocking back and forth, biting their hands and gouging their eyes. Psychological studies have shown that self-abuse is often created by the mind-numbing boredom and emotional neglect of placement in an institution.[12]

A. Children and Adults with Disabilities are Left Behind

While Georgia has engaged in a valuable reform project to close orphanages, children with disabilities have been largely excluded. The primary finding of this report is that the Government of Georgia has undertaken a reform process in a manner that discriminates against children and adults with disabilities detained in institutions.

Georgia’s child care and deinstitutionalization reforms entered its most active phase in 2009. That year, the Georgian government signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, committing itself to the community integration of persons with disabilities. A year earlier in 2008, the US government committed $1 billion in aid to Georgia, setting aside $50 million to improve Georgia’s social services.[13] This was a moment of opportunity for institutionalized children with disabilities in Georgia to be integrated into the community.

Authorities at UNICEF, Georgia’s main strategic partner in planning child care reforms, explained to DRI that they fully intended to support the community integration of children with disabilities into society. They reported to DRI, however, that they made a decision to prioritize the community integration of children without disabilities.[14] According to UNICEF, this would allow them to return to children with disabilities later.

For most children with disabilities in Georgia’s institutions, “later” has never come—and many have died waiting. In the interim, funding for reform has been greatly reduced and the opportunity to help children with disabilities is diminished. Political will to complete deinstitutionalization has faded. This report demonstrates the danger of excluding children with disabilities from all stages of reform.

In 2009, UNICEF hired an independent consultant, Oxford Policy Management, to review the first stages of its child care reform strategy. The consultants warned UNICEF that “the needs of people with disabilities are thought to represent a big gap in service provision…”[15]

Whatever approach may have been intended by international advisors to help the children with disabilities who remain behind in institutions, the Government of Georgia has not fully accepted that all children with disabilities, as a matter of basic human rights, should be integrated into the community:

The strategy is that physically healthy children will not stay in large-scale child care institutions, but be adopted and raised in family-based care—according to the international experience, it is the best option for them. As for children with disabilities, it is reasonable and fairly normal to be brought up in and stay in a child care institution.

– Georgia Minister of Labor, Health and Social Affairs (November 2013)[16]

DRI’s investigation has found that nearly 5 years later, children and adults with disabilities remain largely excluded from Georgia’s reforms. Children with disabilities who are considered by the government as too disabled to benefit from the community services created by the reforms, remain in state-run institutions today.[17]

UNICEF and USAID report that the institutional population in Georgia’s state-run orphanages has decreased by more than 90% since 2005[18]— leaving less than 150 children in state-run institutions.

This number, however, does not include children living in church-run institutions. It does not include the children who live in Georgia’s six residential boarding schools for children with disabilities. Nor does it account for the many children who have been permanently transferred to adult institutions over the course of a decade. As the government was closing state-run orphanages, children were being transferred to these other forms of segregated environments.

The government is playing a shell game with these children.

—Representative of the Georgia Public Defender’s Office (2013)[19]

A spokeswoman for the Georgian Orthodox Church refused to give DRI the number of children under their care during a September 2013 interview—claiming that “a few children” live in informal housing in monasteries across the country.[20] The Director of the Georgian government’s Department of Programs for Social Protection and UNICEF have reported to DRI that they do not know how many children live in Georgia’s church-run institutions, and that they are completely unregulated. One Georgian children’s activist reported to DRI in 2013 that there could be as many as 1,200 children in orphanages run by the Georgian Orthodox Church, while a US Agency for International Development (USAID) representative estimated as many as 1,500.[21] If these estimates are correct, there are approximately 1,650 children with and without disabilities still languishing in Georgia’s orphanages and institutions.[i] The actual number could be larger.

The children in Georgia’s church-run institutions are completely excluded from deinstitutionalization reforms. According to Oxford Policy Management, without any data from these institutions, “…it is impossible even to say whether the total number of children in residential care in the country is going up or down, let alone be able to assess their welfare.”[22]

The government’s lack of information concerning the number or location of children in church-run institutions creates a danger that children could be abused or trafficked without the government’s knowledge.

USAID and the Public Defender’s Office have reported on the transfer of children from state-run institutions to unregulated church-run orphanages:

Sometimes social workers look to the church to find a placement for a child…I think it is a violation of freedom

– USAID representative (2013)[23]

There was a case of one child who changed 6 or 7 institutions. He started in state-run, he went to church, he went to private, back to church, back to private, then I found him back in a state institution, and now—I don’t know where he is. Kids are thrown out all the time from foster care and small group homes because they don’t have enough resources, so they have to put them somewhere…but officially, they will not tell you this

– Representative of the Georgia Public Defender’s Office (2013)[24]

In one state-run institution, DRI interviewed and documented several parents who have had their children taken away from them.[25] According the director of this institution, children were placed by government authorities in unregulated church-run orphanages.[26]

The church needs a license to provide 24-hour residential care and they don’t have such a license. So we have just one possibility: we could go to court. But it’s very difficult to go to court against the church. –Director of Department of Programs for Social Protection, Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs (2013)[27]

The Director of the Georgian government’s Department of Programs for Social Protection reported to DRI that the Georgian Orthodox Church will sometimes seek out vulnerable families and encourage them to hand their children over to the church.[28] It is unknown how many children in private or church-run institutions have disabilities.

While state-run institutions for children without disabilities are being closed, the Georgian Orthodox Church is building new institutions partially financed by the government, with no regulation or oversight.[29] As of September 2013, these children are still excluded from reform efforts.[30]

Given the lack of oversight and monitoring in church-run institutions, there is a risk that children could be subject to human trafficking.[ii] The director of the Georgian government’s Department of Programs for Social Protection reports to DRI that according to law, the transfer of children from state-run to church-run institutions should be regulated by the state, but in reality it is not.[31] According to a Georgian child rights activist, these transfers are performed completely off the record, with no paperwork.[32]

DRI’s concern for the safety of children in unregulated orphanages is heightened by the fact that human trafficking has been publicly identified as a problem in the Republic of Georgia. In 2013, Georgia was downgraded to a “Tier 2” country by the US Department of State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, finding that Georgia no longer met minimum standards necessary to protect persons from sex trafficking, forced labor, or other kinds of modern slavery.[33]

Women and girls from Georgia are subjected to sex trafficking within the country, as well as in Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and, to a lesser extent, Egypt, Greece, Russia, Germany, and Austria.

– US State Department 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report[34]

The complete lack of monitoring of church-run institutions in the current context of the country’s human trafficking record presents dangers to children who are kept in segregated, unregulated and closed-off institutions.

B. Inadequate and Discriminatory Community Services

According to UNICEF, the community services created by the reform thus far are insufficient for children who are perceived to have “complex or severe disabilities.” While children with minimal disabilities have been served, in reality any children with significant disabilities cannot be served by the existing community services. UNICEF reports that the chances for foster care placement for children with severe disabilities, or older children who have been institutionalized most of their life, is “slim to none."[35]

They’re not going to get into foster care, even with intensive support—a lot of kids in these institutions.

– Chief of Child Protection, UNICEF-Georgia (2012)[36]

In the most severe cases we have no option for them. The future for them is to stay in institutions

– Director, Tbilisi Infant House (2011)[37]

Even children with perceived mild disabilities face considerable barriers to leaving institutions. Foster care services are hampered by financial disincentives for potential foster families willing to care for children with disabilities.[38]

Children with disabilities have been completely excluded from all 45 group homes created in the community to enable deinstitutionalization, according to reports from Georgian government and UNICEF officials.[39] Twenty-five of these homes were built with USAID funds, none of which house any children with disabilities, despite the US agency promising in a press release that the initiative would “emphasize the inclusion of children with disabilities.”[40]

We need a certain amount of small group homes for children with disabilities. We don’t have any yet. And honestly, we can’t find a location in the state budget right now for this.

– Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs[41](2012)

In addition to noting the general lack of services for children with disabilities, the 2009 Oxford Policy Management evaluation commissioned by UNICEF stressed the absence of any transitional plan to support children with disabilities aging out of orphanages or community alternatives.[42] “Any good progress made in supporting the development of children up to the age of 18 may be under threat if they are then required to fend for themselves suddenly and without support,” the report warns.[43]

More than 2 years later in November 2011, local advocates reported to DRI that the transition to adulthood remained completely off the agenda for children with disabilities:

They have no choice but to move to the adult institutions after 18 because they have no education, no professional or social skills to take care of themselves and be competitive in the modern society.

– Director of the Georgia Coalition for Independent Living[44](2011)

A few private initiatives have been created to house adults with disabilities, including two rural farming communities and two group homes. However, according to the director of the Georgian government’s Department of Programs for Social Protection, these services are either filled to capacity or have insufficient resources to serve as an alternative to institutionalization for many adults with disabilities.

When children with disabilities turn 18, there are only three possibilities: They can go to the adult institutions in Martkopi, Dzveri or Dusheti.

– Director of the Department of Programs for Social Protection, Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs (2013)[45]

The exclusion of a transition plan to adulthood for children with disabilities has begun to show its consequences: DRI has documented dozens of young adults with disabilities in Georgia’s adult institutions who were minors at the beginning of the reform process. Now, as adults, they will not benefit from any future child care reforms.

C. Abuses in Georgia’s Institutions

Persons with mental disabilities are a particularly vulnerable population in any society, especially those who are shut away and forgotten in segregated institutions. The human rights concerns of institutionalized populations have been documented by such authorities as the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, Paul Hunt, who has identified institutional placement as a threat to the right to health.[46] The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Méndez, has made clear that due to the “fear and anxiety produced by indefinite detention,” placement in an institution can violate the UN Convention against Torture.[47]

From July 2010 to September 2013, DRI documented a broad array of human rights violations against children and adults with disabilities detained in residential institutions in the Republic of Georgia. DRI observed and assessed institutionalized children within Georgia’s state-run orphanages. In the Tbilisi Infant Home, staff report that infants with disabilities are denied life-saving medical care simply because of doctors’ perceptions that the children will not have a good quality of life. As a result, staff report that they can sometimes do little more than wait for children to die in their cribs. In an 18-month period in 2009-2010, local organization Children of Georgia documented a 30% death rate among children with disabilities in the Tbilisi Infant House[48].

Following DRI’s advocacy, in collaboration with local organizations such as Children of Georgia, staff at the Tbilisi Infant Home reported to DRI in 2013 that most children are now receiving care and that mortality rates have dropped sharply. However, during a September 2013 visit to the infant home DRI observed multiple children who were still being denied medical treatment.

Children with spina bifida and hydrocephalus in Georgia’s orphanages are the most likely to be refused medical treatment, according to Children of Georgia.[49] In a single 4-month period between visits by DRI to the orphanage in 2012, 50% of the children with hydrocephalus in the Infant Home passed away (5 of 10 children).[50]

DRI’s investigation revealed that children who are denied life-saving treatment at the beginning of their lives are also refused pain management at the end. None of the children examined by DRI’s pediatric expert who were suffering moderate to severe pain at the Tbilisi Infant’s Home were receiving pain medication.[51]

Pain and discomfort comprises a significant part of these children’s lives.

– Dr. Lawrence Kaplan, Director of Baystate Behavioral-Pediatric Hospital, Massachusetts, USA[52]

According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, the denial of pain medication to children in severe chronic pain may rise to the level of torture under the UN Convention against Torture.[53]

In September 2013, DRI investigators witnessed a 2-year old child lying in a crib with untreated hydrocephalus. His head had swelled to the size of a basketball, rendering him completely immobile. No pain medication was prescribed for the child. Staff reported that the only method for managing this child’s pain was to give him sleeping pills.[54]

In the Senaki orphanage for older children with disabilities, DRI documented several malnourished children who, according to staff, were bedridden and spent most of the day confined to their cribs.

In one case, DRI found an emaciated 7-year old girl named Mariam in a dark back room of the institution in the middle of the day—alone and screaming. The girl was covered in bedsores and had atrophied limbs. She died one month after DRI’s visit.

Those who survive to adulthood are warehoused indefinitely in large-scale institutions—some built with funding from the US government.

Georgian law on legal capacity is not consistent with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and contributes to the denial of rights.[55] Adult residents of institutions are routinely stripped of their legal capacity and put under state guardianship—a process which denies the person of any control of his or her financial, legal and personal life.

Even adults who retain their legal personhood are often at the mercy of the institution in which they live to exercise their rights. DRI has documented three couples living in institutions who have been forcefully separated from newborn children with no judicial review.

Rehabilitation programs are nearly non-existent.[56] Residents in one institution reported to DRI investigators that the only activities they have to do all day is knit or listen to music.[57] According to the directors of two adult institutions, residents are often forced to do unpaid jobs as a form of “work therapy.”[58] In some instances, the Georgia Public Defender’s Office has reported that staff take residents home to work on their farms or do household chores.[59]

D. New Investments in Segregated Institutions by International Donors

States Parties to the present Convention recognize the equal right of all persons with disabilities to live in the community, with choices equal to others, and shall take effective and appropriate measures to facilitate full enjoyment by persons with disabilities of this right and their full inclusion and participation in the community…

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Article 19)

Adults with disabilities are warehoused for a lifetime in Georgia’s adult institutions. Despite adoption of a national Disability Action Plan in 2010 to promote inclusion of persons with disabilities in society, the Georgian government has since increased the number of long-term institutions for adults with disabilities—using US government funding.

The Georgian government has used nearly $1 million in international aid from the United States government to open two new, long-term institutions for adults. While undoubtedly well-intentioned, this international development aid has resulted in the perpetuation of institutional care in a country with a stated commitment to deinstitutionalization.

Costly improvements in the physical conditions of existing institutions, which are often proposed as a response to finding substandard care, are also problematic because they fail to change the institutional culture and make it more difficult to close these institutions in the long-term.

- European Commission Ad-Hoc Expert Group on the Transition from Institutional to Community-Based Care[60]

The US government financed the reconstruction of the Martkopi institution, a new institution for 68 adults with disabilities located in a remote area 40km outside Tbilisi. The US European Command donated $500,000 for the main rebuilding project, and USAID donated $100,000 for furniture and equipment.[61] Children who have aged out of Georgia’s orphanages, and who did not benefit from the deinstitutionalization of children’s services, have been sent to Martkopi, where they will live indefinitely.[62]

The US government has characterized the facility as promoting “family style” or “apartment style” living.[63] DRI investigators found this characterization to be wholly inaccurate.

The facility consists of 3 floors that sleep approximately 23 men and women on each floor. Most rooms have 4 beds, and all bathrooms, the day room, and the dining room are communal. The staffing of the institution, which consists of 13 caretakers for 68 residents during the day—and only one caretaker per floor at night— makes any meaningful rehabilitation or habilitation impossible.[64] Most residents in wheelchairs are restricted to the third floor—where they are fed in their rooms. According to a 2013 report by the Georgia Public Defender’s Office, since staff have turned off the elevator to prevent residents from using it, the residents in wheelchairs cannot eat in the first-floor dining room or access the second-floor day room, without being carried down stairs by staff. DRI interviewed several residents who were forcefully separated from their children or parents when they were moved to the Martkopi institution. The facility at Martkopi is most accurately described as a segregated large-scale institution that was renovated specifically to warehouse persons with disabilities.

I was brought up without a mother, and without a mother’s love, and I don’t want my child to grow up without a mother

– Mother in the US-funded Martkopi adult institution whose 10-month old child was taken away from her (2012)[65]

She can independently take care of her child…there is no reason to take her child away from her

– Director, Martkopi institution (2012)

The US government also spent $300,000 on the construction of the new long-term Temi institution for 30 adults with disabilities in the rural village of Gremi.[66] “You can see the deprivation of people,” a student volunteer told DRI in Temi, regarding the residents with disabilities. “It’s challenging because they never get supported….and we have to work with the caretakers who have no professional training.”[67]

In addition to funding the Martkopi and Temi institutions, the US government has also invested funds to improve the physical infrastructure of both the Tbilisi Infant Home and the Senaki orphanage for children with disabilities, where DRI has documented extensive neglect and abuse.[iii] In 2008, UNICEF reports that the UN agency spent “hundreds of thousands of euros” to rebuild two wings of the Senaki orphanage.[68]

________________________________________________

[i] UNICEF’s estimate as of Sept. 2013 is that 150 children with disabilities remain in state-run orphanages. The government does not know how many children live in church-run orphanages. As described below, local activists have reported to DRI that as many as 1,500 children live in Georgia’s orphanages run by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

[ii] DRI has not documented instances of human trafficking and is not suggesting that the Georgian Orthodox Church is committing trafficking by operating unregulated orphanages. The risk of human trafficking is created wherever there is no oversight and it is impossible to monitor or identify the location of children by family members or government authorities. It is especially likely for criminal activity to occur in a closed environment in which independent human rights monitoring does not take place. The United Nations defines human trafficking as: “…the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.”

[iii] USAID financed a playground and landscaping at the Tbilisi Infant’s House, and the US State Department financed a computer room and gym at the Senaki Institution for children with disabilities.

Summary of Recommendations

Legal recognition of the rights of persons with disabilities is gaining ground around the world. Since the adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), governments have begun reforming laws and social service systems to protect the basic rights of people with disabilities. The CRPD’s article 19 now recognizes the right of “all persons with disabilities to live in the community, with choices equal to others.”[69] To implement this right, governments must take immediate action to reform social services to provide the supports necessary for community integration. Under the new UN “Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children,” governments must begin to plan for the “elimination” of institutions for children.[70]

In 2009, the Republic of Georgia signed the CRPD and committed itself to the treaty’s principle of inclusion. While taking valuable steps to integrate non-disabled children into society, Georgia chose to leave the most vulnerable people behind—children and adults with disabilities. Institutionalized infants with complex disabilities, older children with disabilities who have spent entire lives in institutions, and adults with disabilities have been essentially written off by the Republic of Georgia—violating the prohibition against discrimination under article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

International development organizations which fund and implement aid programs must comply with article 32 of the CRPD which mandates that “international cooperation, including international development programmes, is inclusive of and accessible to persons with disabilities.”

By leaving out institutionalized children with disabilities from reform plans, international agencies’ assistance to Georgia has discriminated against persons with disabilities. Georgia and international donor organizations have failed to live up to the obligations of CRPD articles 19 and 32.

In 2013, the Republic of Georgia is again at a crossroads. If Georgia chooses to address these gaps in an otherwise ambitious and aggressive reform effort, it has the potential to become the region’s first country to fully integrate children with disabilities into society.

If Georgia fails to take immediate action to include all persons with disabilities in its deinstitutionalization reforms, the potential for true change will be lost—replaced by cosmetic reforms that leave the true stakeholders continuing to suffer in abusive institutions, more invisible and silenced than ever before.

A. Ensure Persons with Disabilities’ Right to Live in the Community

Article 19 of the CRPD requires governments to take immediate steps toward the community integration of children and adults with disabilities. Reform programs that exclude persons with disabilities are discriminatory and violate this right.

Georgia’s experience with deinstitutionalization provides a key lesson for other countries undergoing deinstitutionalization as they implement article 19 of the CRPD: children and adults with disabilities should be included from the beginning of the reform process. The creation of supports which allow all persons to live in a family setting in the community is essential. This is true regardless of the perceived severity of their disability.[iv]

Despite UNICEF’s declaration that Georgia’s three state-run orphanages for children with disabilities would be closed by the end of 2012,[71] this goal remains unachieved. Services in the community remain inadequate to support the deinstitutionalization of persons with disabilities, and the funding and political will that existed at the beginning of the reform process are now gone.

Adults with disabilities are warehoused indefinitely in new institutions built with international development funds. This violates the spirit of USAID’s disability policy, and this policy should be amended and clarified to make clear that such funding violates US law.

In many countries, individuals with disabilities have been ‘warehoused’ in abysmal conditions with total disrespect for their rights. Those rights must be respected.

— Disability Policy, US Agency for International Development[72]

In institutions supported by international development funds in the Republic of Georgia, DRI investigators witnessed infants dying slow painful deaths because of the intentional withholding of medical care; children who are subjected to the neglect and lack of stimulation that leads to self-abuse; and children whose disabilities were so worsened by lack of appropriate one-on-one care that they had become permanently bed-ridden.

Key Recommendations

- The Georgian government should (A) commit the financial resources necessary to deinstitutionalize children and adults with disabilities who remain in state-run institutions, and to create community-based alternatives with appropriate services and safeguards; and (B) create the community supports necessary to plan for the elimination of all institutions for children, including private and church-run facilities;

- UNICEF should develop a global statement of best practices mandating that country offices do not discriminate against children with disabilities in planning for deinstitutionalization and service system reform as documented in Georgia. Instead of coming last, children with disabilities should be part of every aspect of reforms;

- The United States should take immediate action to ensure that future investments in segregated care do not occur—either in Georgia or elsewhere in the world. The USAID Disability Policy should be updated to reflect such a prohibition. The US Department of Defense and the US Department of State should adopt similar comprehensive disability policies in regard to international aid programs;

- The United States contributed to the current segregated system, and has a responsibility to undo the effects of its misguided efforts that have left adults with disabilities segregated from society. These adults face the prospect of remaining segregated for a life-time in US-funded institutions. The US should commit to providing the funding necessary to deinstitutionalize immediately the persons with disabilities detained in Georgia’s US-funded institutions and to develop appropriate community services to allow them to live full, meaningful lives in the community.

B. Ensure Access to Healthcare

Children with disabilities routinely die in Georgia’s orphanages due to the denial of life-saving surgeries which are available and affordable in the Republic of Georgia. Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states that nations must provide the highest attainable services and facilities to all children and must “strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to such health care services.”[73]

Article 25 of the CRPD mandates that States “[p]revent discriminatory denial of health care or health services…on the basis of disability.” And further, that States provide “services designed to minimize and prevent further disabilities, including among children…”[74]

Furthermore, the denial of pain medication to children in severe chronic pain in the Tbilisi Infant Home may rise to the level of torture under the UN Convention against Torture. In February 2013, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Méndez, released a report detailing the types of abuses in healthcare settings which could rise to the level of torture or ill-treatment under international law. Méndez concluded that when authorities deny pain treatment which “…condemns patients to unnecessary suffering from pain, States not only fall foul of the right to health but may also violate an affirmative obligation under the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment.”[75]

Such a determination would require the criminal prosecution of responsible authorities, in accordance with article 7 of the Convention against Torture.

Key Recommendations

- The Georgian government should establish a monitoring system to ensure that children with hydrocephalus and spina bifida receive immediate medical treatment, as well as appropriate follow-up care;

- The Georgian government should ensure the availability and accessibility of pain medications to children suffering painful conditions in the Tbilisi Infant Home;

- The Georgian government should prepare a country-wide system of community-based health centers for providing healthcare and support for children and adults with disabilities. The Tbilisi Infant Home should be closed—or transformed into a non-residential center for expertise and training.

C. Protect Children from Trafficking

In the Republic of Georgia, the lack of oversight, regulation, or monitoring of church orphanages puts all children – especially children with disabilities – in great danger. According to a UNICEF representative, orphanages run by the Georgian Orthodox Church are “completely unregulated.”[76] The representative explained that because the church is “very powerful,” it has become a sensitive political issue.

The director of the Georgian government’s Department of Programs for Social Protection confirmed to DRI that the church-run institutions in Georgia were unlicensed to house children, but that it would be “very difficult,” to challenge the church.

Recent DRI investigations in Guatemala and Mexico have found that trafficking is allowed to flourish behind the closed doors of institutions—with no oversight, regulations or regular monitoring. And various organizations around the world have demonstrated that children are all too often trafficked from orphanages into prostitution rings, as exposed in Russia, China, Cambodia, Portugal, India and more.[77]

Key Recommendations

- The Georgian government should establish independent safeguards and oversight mechanisms within private and church-run institutions to protect against trafficking, exploitation, violence and abuse;

- The Georgian government should create a registry of children and adults in all institutions. A system for tracking admissions, discharges, deaths, and transfers of persons between institutions or to other placements should be created, so that they cannot disappear from society. Information about the total number and characteristics of persons receiving services should be published and made public.

________________________________

[iv] Successful disability reforms have demonstrated that it is feasible and immensely beneficial to bring people with the most severe disabilities into inclusive, small, family-like settings. For example, such as has been accomplished in the United States at Pennsylvania’s Pennhurst Institution, Oklahoma’s Hissom Memorial Center, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s national self-determination initiatives.

I. Introduction: Political and Social Context of Reforms

The Republic of Georgia has been described by historians as a country that has existed throughout history on the edge of empires, continually overshadowed on the world stage by its more illustrious neighbors—Russia to the north, historical Persia to the south-east, and Turkey to the west.[78]

Recent history, however, has brought Georgia into the international spotlight. In the years following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, Georgia existed in a state of near-collapse marked by corruption, poverty and bloody periods of civil war.[79] First Step of Georgia, a service provider for children with disabilities in Georgia, described the collapse of organizational structures during this time as chaos, when “many of the basic human needs that we simply take for granted – food, utilities, healthcare, education, social services – were at best sporadic and at worst, non-existent for periods of time.”[80]

It was during this time that the first stages of child care reform began. Following Georgia’s 1994 ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, pilot programs for prevention of child abandonment launched in 1999, recruiting the country’s first social workers and providing cash assistance to families with children at risk of institutionalization. A national action plan for child care reform was drafted in 2002, but was never enacted and later abolished.[81]

Social discontent climaxed in 2003. Outraged over dubious election results, protestors took to the streets en masse sparking the peaceful “Rose Revolution” symbolized by the red roses offered by protestors to deployed military forces. On November 23rd, Communist-era President Eduard Shevardnadze peacefully resigned.[84] According to the BBC, not a single person was injured during the revolution. Opposition leader Mikhail Saakashvili and his United National Movement party were subsequently elected to power.[83]

The election of Saakashvili marked a turning point in the nation’s economic history. Georgia’s economic growth rate quickly became one of the highest in the region, with gross domestic product rising from $4 billion in 2003 to $10 billion in 2007.[84]

This economic upturn spurred the second stage of reforms for children, which focused on dismantling Soviet-era governmental structures and establishing a government commission on Child Protection and Deinstitutionalization.

However, violence in Georgia’s breakaway provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia continued to escalate. In early August 2008, firefights between the Georgian military and Russia-backed South Ossetian forces eventually led to the invasion of Russian forces into Georgia, displacing more than 20,000 Georgians and disrupting the Georgian economy. On August 12, a cease-fire was signed and advancing Russian troops halted en route to Georgia’s capital city of Tbilisi.[85]

With then-U.S. Senator Joseph Biden calling the Russian invasion of Georgia, “one of the most significant events to occur in Europe since the end of Communism,” the US pledged $1 billion dollars in assistance to stabilize Georgia’s economy, improve infrastructure and provide humanitarian assistance. Georgia became one of the world’s largest per capita recipients of US economic assistance.[86]

Georgia’s child care reform entered its most active phase following this substantive influx of foreign aid in 2008, of which nearly $50 million was earmarked for health and social infrastructure projects.[87] The government’s Child Action Plan for 2008-2011 was adopted and large-scale institutions began to close in favor of re-integration with biological families, adoption, foster care and small group homes in the community.

By the time implementation of the Government’s Child Action Plan for 2008-2011 was in full swing in 2009, the Georgian government budget allocations for social welfare stood at an all-time high of 25% of total state expenditures, up from 11% in 2003.[88] In July 2009, Georgia signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, committing to the community integration of persons with disabilities. And approximately $50 million of US aid stood ready to improve Georgia’s social services.[89] If there was ever a moment of opportunity for institutionalized children with disabilities in Georgia, this was it.

II. Observations

Over the course of a three-year investigation from July 2010 to September 2013, Disability Rights International (DRI) documented the human rights situation for the Republic of Georgia’s most vulnerable population— persons with disabilities detained in institutions including orphanages and adult social care homes.

Despite the country’s ambitious child care reform plan, children and adults with disabilities in institutions have been largely excluded from the country’s reforms. Children with disabilities remain at high risk for life-threatening medical neglect in Georgia’s orphanages; older children in orphanages are not eligible to take advantage of existing community services; and adults with disabilities are warehoused indefinitely—many in institutions built with foreign assistance funds.

A. Denial of Medical Care for Children with Disabilities

DRI documented a broad range of medical neglect in the Republic of Georgia’s orphanages, including the discriminatory denial of life-saving surgeries, dangerous medical practices and denial of pain medication.

The Tbilisi Infant Home in the center of Georgia’s capital city houses, at any given time, approximately 40-60 children with disabilities from age 0 to 6. In recent years, DRI has documented a mortality rate for children with disabilities at the orphanage as high as 50%[90][v] About 20 of the children with disabilities are labeled by the institution as severe and kept separated from the rest of the children in two dimly lit rooms lined with rows of cribs. Over 5 visits to the orphanage, DRI observed that most of the children with disabilities were kept in cribs even in the middle of the day. The children were often completely silent – awake, but not crying – a characteristic common of babies in institutions who have given up on crying as a means of receiving care or attention. Toys and stuffed animals are nailed to the wall, above cribs, out of reach. DRI investigators noticed drawn curtains even on bright, sunny days.

Between the two buildings that made up the orphanage was a playground, funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID). During all of DRI’s visits to the orphanage, investigators never saw any children outside.

Many children in the institution are not true orphans, but are given up to the orphanage for reasons of poverty, social stigma or disability. Indeed, UNICEF reports that 90% of children in Georgia’s orphanages have at least one living parent.[91]

Many doctors pressure parents to give a child with a disability up to the orphanage at birth, according to the Tbilisi Infant Home director, telling them the future for their child is hopeless. The local organization Children of Georgia reported to DRI that many parents of children with complex medical conditions are faced with a difficult decision: They must choose between keeping their child at home without sufficient insurance to cover medical costs, or abandon their child to the orphanage in order to receive full coverage.[vi]

Mortality of children with spina bifida and hydrocephalus

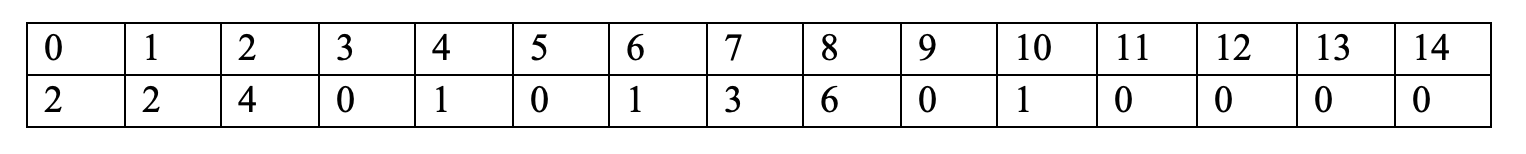

In the Tbilisi Infant Home, children with spina bifida and hydrocephalus are among the most likely to die preventable deaths, according to Children of Georgia.[92] In a 5-year period from 2008 to 2012, 58% percent of all children with spina bifida or hydrocephalus admitted to the Tbilisi Infant’s Home died, according to Children of Georgia[93], due to the denial of surgical intervention to treat the condition at birth or upon diagnosis.[vii]

Hydrocephalus is an abnormal buildup of cerebral spinal fluid in the skull. When left untreated, hydrocephalus is fatal in most cases.[94] However, when appropriate treatment is provided, the mortality rate of children who die from hydrocephalus is between 0 to 3 percent.[95] It is most commonly treated by inserting a tube, called a “shunt,” to drain away the excess fluid and relieve the pressure on the brain.[96] This procedure is regularly denied to children in the infant home despite being affordable[viii] and available in the Republic of Georgia.[97]

In a single 4-month period between visits by DRI to the orphanage in 2012, 50% of the children with hydrocephalus in the Infant Home passed away.

On a 2011 visit, DRI investigators observed a particularly haunting scene. A child with hydrocephalus lay still in his crib in a dark corner of the orphanage. The child was only six months old but the built-up fluid had ballooned his head to nearly three times the normal size. His head was covered in open wounds— the expanding skull stretching his skin so tight that the pressure from his blankets and pillow would rip open his skin. Staff informed DRI that the child would die anytime. Indeed, when DRI visited again four months later, the child had died, and a new admission with untreated hydrocephalus had taken his place.

Upon reviewing medical records of current residents with untreated hydrocephalus in June 2012, DRI’s pediatric expert, Dr. Lawrence Kaplan,[ix] observed that all the children would have benefited from the insertion of a shunt at the time of original diagnosis, and that the near-death condition of the children was not due to the severity of their illness, but rather to a decision to not treat their condition at an earlier stage.[98]

The assessment further revealed that the majority of children in the orphanage labeled as “terminally ill” would likely survive if provided with immediate medical treatment.

…those with hydrocephalus are in this reviewer’s opinion being abused and neglected.

-Dr. Lawrence Kaplan, Director of Baystate Behavioral-Pediatric Hospital, Massachusetts, USA

Discrimination on basis of disability

The denial of medical care on the basis of disability is a form of discrimination. Approximately a third of children with hydrocephalus will develop some degree of an intellectual disability.[99] The probability and severity of this risk increases the longer a child goes untreated.[100] Tbilisi Infant Home staff reported to DRI that neurologists who determine the suitability of a child for receiving a shunt base their decision on the child’s prospects to develop what they consider to be a good quality of life.[101] Staff reported to DRI that the children in the orphanage would not receive treatment because they were deemed by the doctors to be “hopeless,” and to “have no future.”[102]

The first huge mistake is in maternity wards. Doctors say to a mother that it is hopeless and the child will die.

– Director, Tbilisi Infant’s House (2011)[103]

…it appears very likely that the expectation of those who cared for the children prior to their admission to the Tbilisi Infant Home was that they were being placed there to die.

– Dr. Lawrence Kaplan, DRI pediatric expert

Infant home staff have reported to DRI that hospitals will sometimes turn away children with disabilities without examining them. The Director of Neurology at Tbilisi’s Iashvili Children’s Hospital echoed this concern:

I don’t want to name the hospitals and clinics…but there were cases when people from the infant house took children to hospitals and they refused to treat the children.

– Director of Neurology, Iashvili Children’s Hospital (2012)[104]

During a visit to the Tbilisi Infant’s Home by DRI in 2012, a one-year-old boy with untreated hydrocephalus had just returned to the orphanage after being admitted to the Iashvili Children’s Hospital for vomiting and respiratory distress. Despite a request for a consultation from the hospital’s neurology department regarding the child’s hydrocephalus, the child was returned to the orphanage with no indication as to the result of the neurologist’s examination, or even to whether an examination had taken place at all.[105]

Medical professionals in Georgia cite the high risk of complications and infection after placing a shunt as justification for refusing treatment.[106] In countries where treatment is provided, complications are not uncommon; thirty to forty percent of shunts placed in pediatric patients will fail within 1 year, with infection as a common cause.[107]

When hydrocephalus is treated and managed, however, the prognosis is good. The majority of children who receive shunts and appropriate follow-up care reach adulthood. In the US, a study found that more than half graduate from mainstream education.[108]

Denial of pain medication

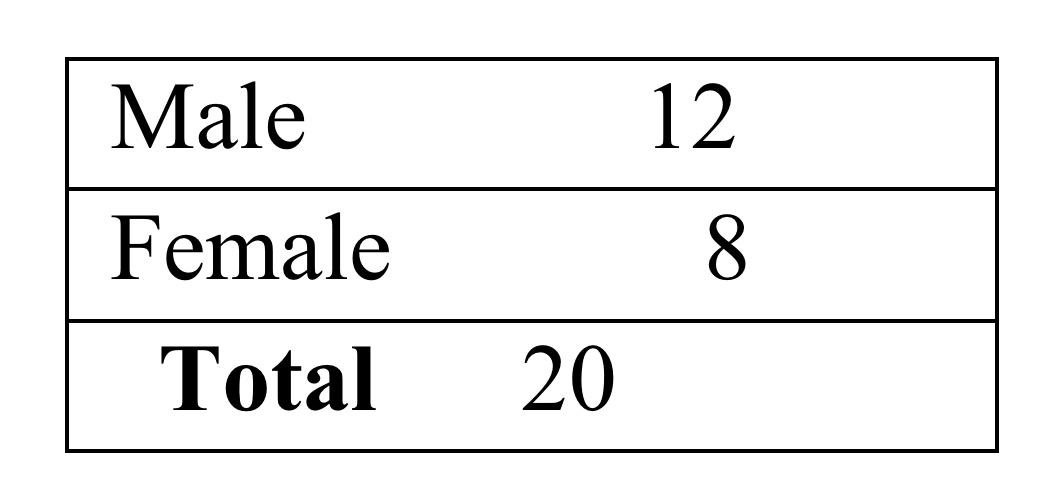

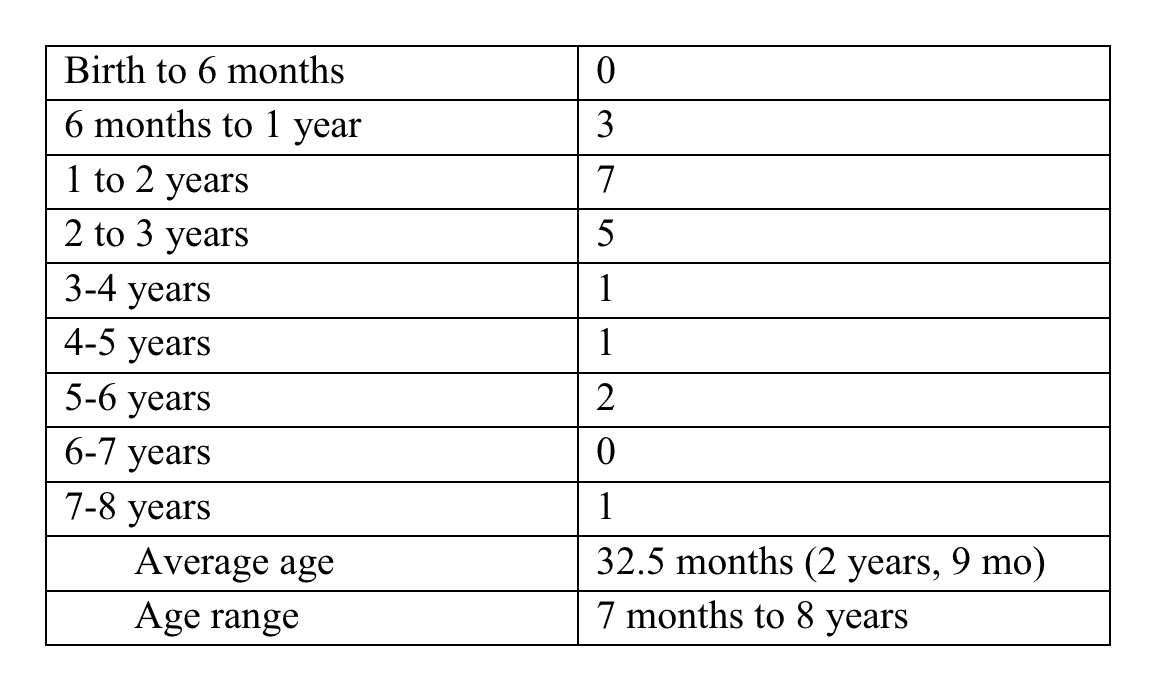

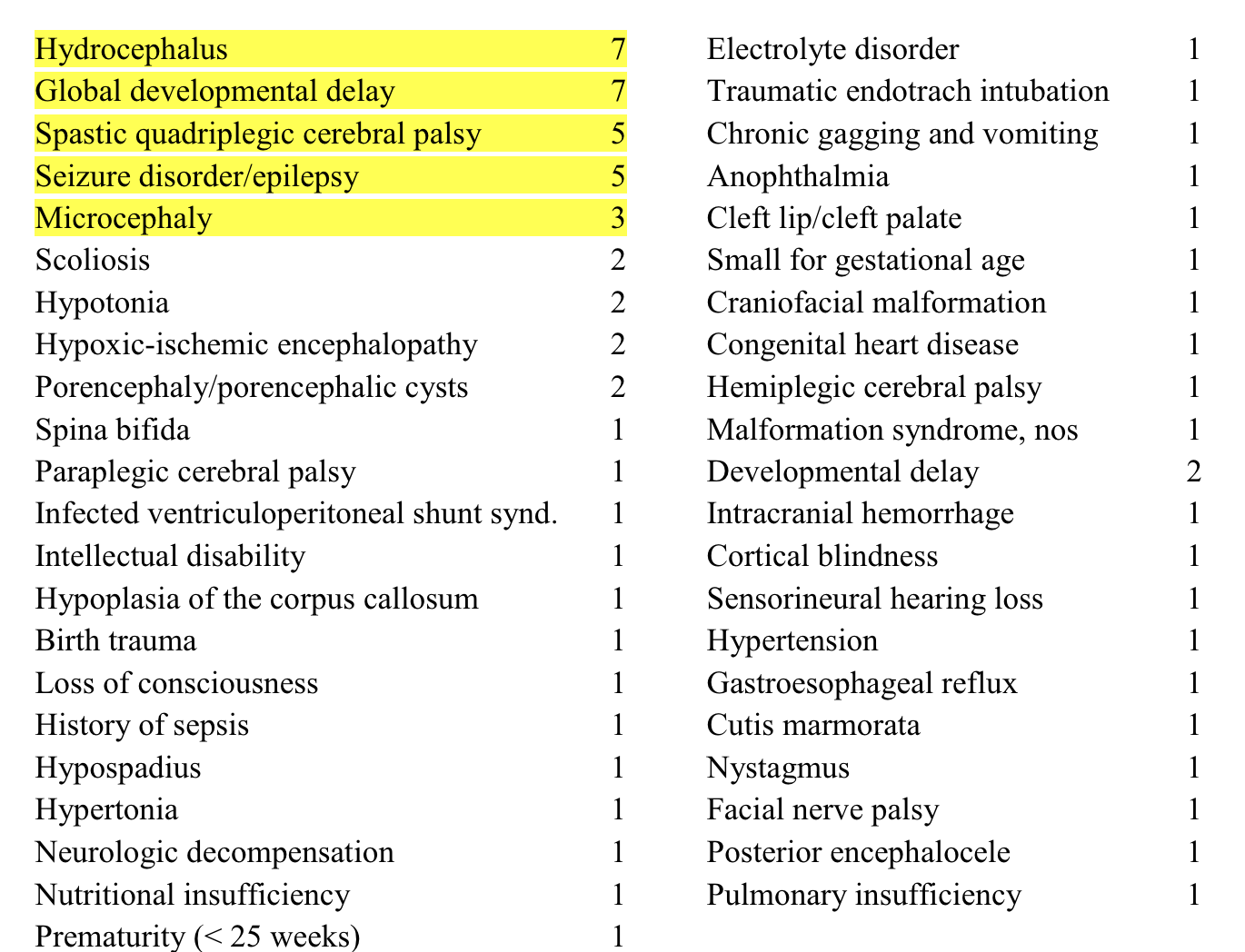

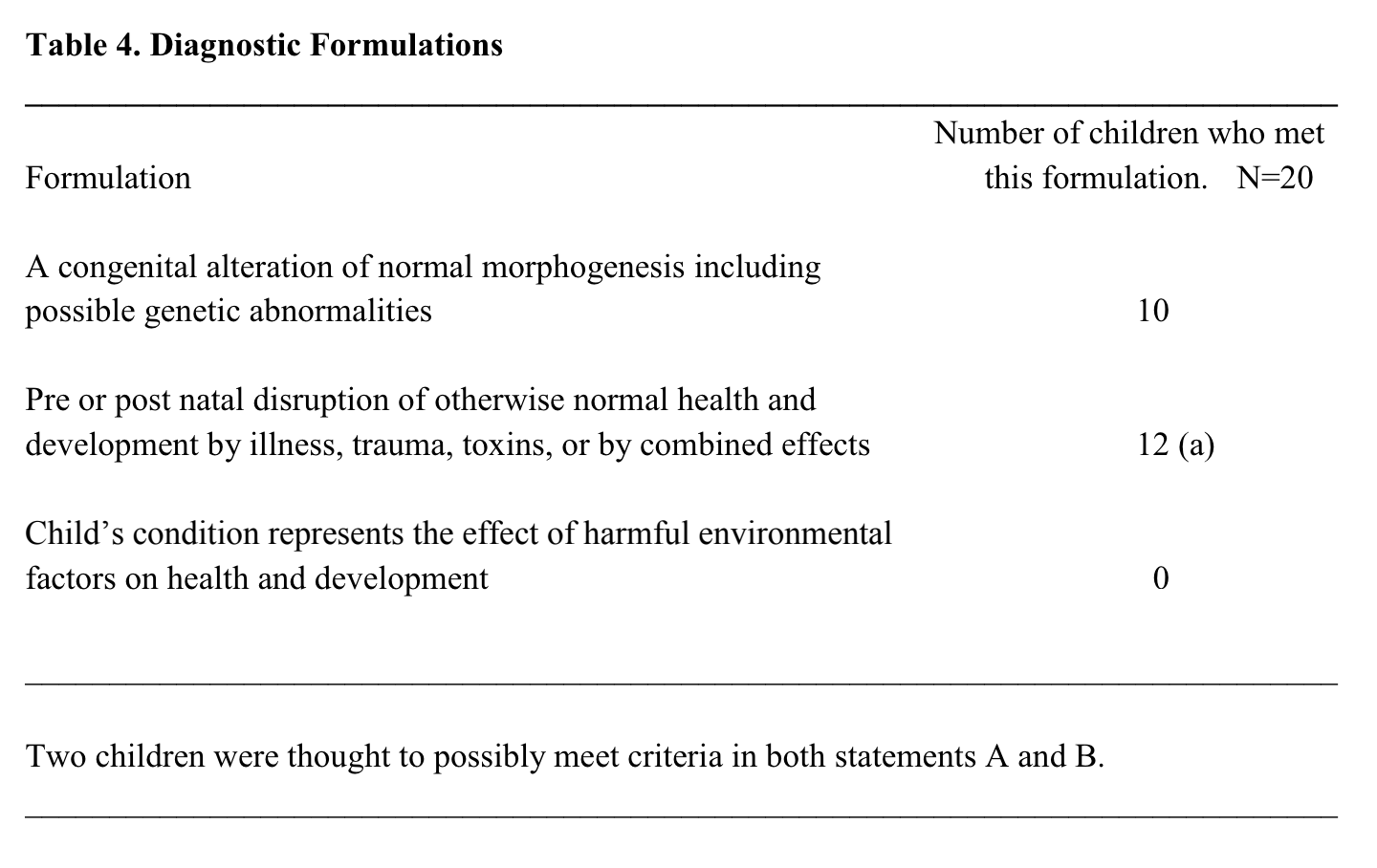

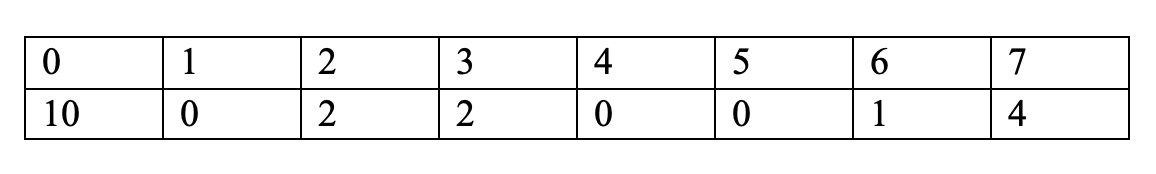

Children who are denied life-saving treatment at the beginning of their lives are also refused pain management at the end. DRI’s medical expert Dr. Lawrence Kaplan conducted an in-depth medical assessment of 20 of the children with disabilities at the Tbilisi Infant Home. His assessment found that 10 of the children suffered from moderate to very severe chronic pain[x]. None of these children received any pain medication.

DRI observed many children who appeared to be near-death, lying motionless in cribs and covered in bed sores.

Pain and discomfort comprises a significant part of these children’s lives.

- Dr. Lawrence Kaplan, Director of Baystate Behavioral-Pediatric Hospital, Massachusetts, USA

The two children with the most severe chronic pain were among those who were refused treatment for hydrocephalus. DRI observed one of these children, a 1-year-old girl, crying out in pain and vomiting during a brief medical examination by orphanage caretakers.[109]

Dangerous medical practices and lack of habilitative services

Nearly all the children with disabilities assessed by DRI in the Tbilisi Infant Home[xi] have cerebral palsy and need assistance in order to learn how to stand, walk, or use a wheelchair.[110]

The orphanage lacks physical therapists, occupational therapists, communication therapists, and nutritional and dietary consultants. Except for wheelchairs, the orphanage has no basic equipment necessary for children with disabilities, including adaptive seating and orthotic devices.[111]

There was a striking absence of habilitative resources which would be requisite for the health and well-being of the range of needs these children have.

– Lawrence Kaplan MD, ScM.

Without physical therapy or sufficient movement and interaction by caretakers, the children assessed by DRI experts in the orphanage are at risk for developing conditions such as joint contractures, hip dislocation, scoliosis, bed sores and chronic pain.[xii] DRI observed several children who would be at risk of becoming permanently bed-ridden without immediate intervention.

Protracted inactivity of remaining in a crib can be dangerous for any child in terms of their physical development, as well as their psychological health.[112] It is detrimental for children to lie on their backs in a crib for prolonged periods of time. When this happens, their heads flatten and their bones don’t grow properly because gravity does not pull on them at the proper angle. As such, many children who grow up in cribs remain small.[113] Children with abnormal movement or children with limited movement only degenerate in cribs without consistent therapy. According to developmental disabilities nurse Karen Green McGowan, these children need consistent care, so that on a neurological level their brains will develop healthy movement patterns and on a physical level, they will develop the muscle tone and bone for actual movement.

To maximize growth and development, experts recommend that children have a care plan that consists of “feeding, sleeping, physical therapy, play, other ways to foster growth and development, medications, psychosocial needs, family needs, and pain assessment/management.”[114] This level of care is a level that most institutions cannot provide. Rather, it is the level of care that parents or other consistent care-givers naturally provide their children 24 hours a day.

Just getting out of bed and being held and moved around can be life-saving.

– Karen Green McGowan, RN, CDDN, DRI Expert, President-Elect of the Development Disabilities Nurses Association.

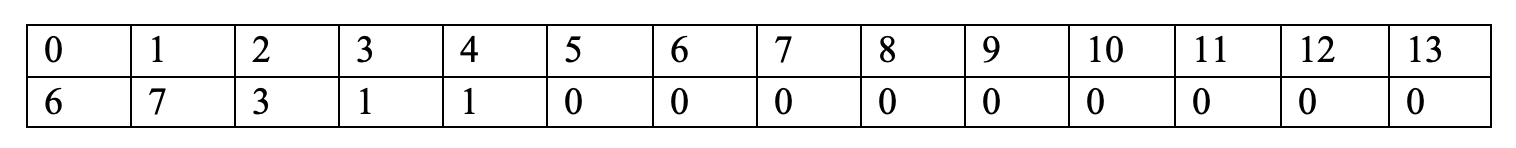

It is generally common for children with complex physical disabilities, and particularly cerebral palsy, to have trouble eating or swallowing. This can lead to “pulmonary aspiration,” where food or saliva enters the lungs, often resulting in pneumonia or death from asphyxiation.[115]In the Tbilisi Infant Home, infants spend the majority of the day and night on their backs in cribs, making swallowing an even more challenging task. In an 18-month period in 2009-2010, 15 children in the orphanage died from pneumonia, according to Children of Georgia.[116]

DRI’s medical experts observed that the Tbilisi Infant Home lacks infection control procedures, including appropriate hand washing and decontamination procedures. DRI observed one child with a highly contagious infection, which in the absence of appropriate precautions, presented serious risks for every child in the orphanage.[117] In the same 18-month period, infection played a role in at least 10 deaths.[118]

The orphanage’s medical staff also reported the common usage of Depakote, an antiepileptic seizure medication, on children under 3 years of age. Studies have shown that this medication on children under 3 years of age presents a high risk of liver failure.[119]

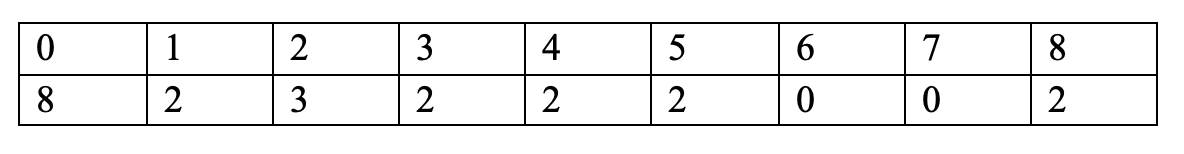

Children who receive little stimulation and are emotionally deprived of a relationship can develop a medical condition known as failure to thrive, which can lead to permanent emotional, mental and physical developmental deficits.[120] Even children who receive adequate food in clean institutions may become disabled; some children become so emotionally neglected that they will not eat – and they may become malnourished and die.[121] The staffing levels at the infant home cannot provide the consistent care and emotional support that a mother or father can provide. The director informed DRI during a 2012 visit that the staff consists of 3 caregivers assigned for every group of 10-13 children. DRI observed, however, that in practice there are often only 2 caregivers present at any given time. Each caregiver works a 24-hour shift every three days.[122]

Nine of the children assessed by DRI’s pediatric expert in the Tbilisi Infant Home showed evidence of failure to thrive.[123]

Developing an early emotional connection to a caregiver is also critical for an infant’s well-being. Absence of attachment to a consistent caregiver…can have significant negative effects on brain development and cognitive functioning.[124]

– World Health Organization

The children that I saw in the Tbilisi Infant Home were simply not getting enough nurturing, as in mothering, and that is more important than movement in terms of keeping children alive. …We have learned from long, hard experience that babies and young children who grow up without nurturing often die.

– Karen Green McGowan, RN, CDDN, DRI Expert, President-Elect of the Development Disabilities Nurses Association.

Barriers to medical care

The local organization Children of Georgia cites additional barriers to receiving appropriate medical care for spina bifida and hydrocephalus in Georgia. Insurance in Georgia will not cover diagnostic tests such as an MRI, according to Children of Georgia. The organization reports that despite the presence of visual symptoms in many children, Georgia’s insurance will not pay for the necessary surgeries until the diagnostic tests have been performed.[125]

As a result, parents in Georgia are faced with a daunting decision. They can delay treatment to save the money necessary for diagnostics and thereby risk increased disability and chance of death for their child; or they can give the child up to the Tbilisi Infant’s Home, where the child will be covered by insurance for all procedures, including diagnostics, according to Children of Georgia.

Neither scenario ends well for the child. When a child is relinquished to the infant home in order to receive coverage, there are considerable waiting times for insurance companies to process paper work, often resulting in a delay between every step of the process (diagnostics, examination, and surgery), according to the director of the Tbilisi Infant’s Home. The director reported to DRI that by the time the child is approved for surgery, the doctor will sometimes refuse treatment based on the child’s chances for a perceived good quality of life.

As of September 2012, of the 36 children with spina bifida or hydrocephalus admitted to the infant home in the past five years, 21 had died and 14 were still in the orphanage. Only 1 child was ever reunited with his family.[126]

Parents who do keep their child need time to save money for diagnostic treatments, leading to the child experiencing deterioration in health and increased disability. This deterioration can similarly result in denial of surgery and abandonment of the child to the orphanage.

DRI documented medical neglect in the Senaki Orphanage for children with disabilities, a three-story building in the northwest region of the country housing 50 children age 7-18. The director of the Tbilisi Infant Home, as well as the Georgia Public Defender’s Office, have expressed concern that there is no intensive care clinic near Senaki, and that the nearest hospital equipped to care for children with complex medical needs is more than an hour away.[127]

DRI has documented several bed-ridden children with atrophied muscles in the Senaki institution for older children with disabilities age 7 to 18 who, according to the director of the institution, have spent their entire lives in cribs.

DRI investigators found a young girl named Mariam who was transferred from the Tbilisi Infant Home to the Senaki Institution for children with disabilities at age 6. One year after her transfer, in October 2011, DRI found 7-year old Mariam in a dark back room of the institution in the middle of the day—alone and screaming. The girl was covered in bedsores and had atrophied limbs—both avoidable and very dangerous products of lack of care in the institution.

Upon request by DRI,[xiii] Senaki’s pediatrician provided DRI with an evaluation of Mariam’s condition in October 2011. In addition to her primary diagnosis of cerebral palsy, the medical evaluation revealed that she “has not had food for a number of days,” and had extensive bedsores[xiv] from lying in bed for long periods of time. Mariam also had “multiple fractures of lower limbs, which are now healed with deformities of legs.”[128] DRI arranged for an independent pediatrician to travel to Senaki to give a second-opinion on Mariam’s condition and evaluate options for medical interventions. Authorities later informed DRI that Mariam died the day before DRI’s pediatrician was scheduled to arrive.[129]

During a 2012 visit to Senaki, DRI’s pediatric expert observed Giorgi,[xv] another severely malnourished and emaciated 8 year old boy with cerebral palsy lying in a crib. Staff reported that he was brought to the orphanage 4 months earlier by his mother because she was no longer able to support him at home. According to staff, he was already severely underweight at the time of admission, but his weight had dropped even further to 15 kgs (33 lbs) after placement in the institution.

Giorgi had bedsores on the side of his head from lying in bed for too long without being moved. He spends his days and nights in a crib that DRI observed was infested with bugs.[130]

I suspect his bed has vomit in or around the frame and springs which is attracting the bugs

– Lawrence Kaplan MD, ScM, FAAP.

Staff told DRI that being separated from Giorgi had caused the mother to become depressed, and that she called the orphanage every day.

On the same visit to the Senaki institution, DRI observed a staff member grasping the hands of a self-abusive teenager, who would hit himself if left unrestrained.

Self-abuse is created and exacerbated among children who receive no love and attention…Psychological experts agree that they crave some form of stimulus, so they would rather feel pain than feel nothing.

– Karen Green McGowan, RN, CDDN, DRI Expert, President-Elect of the Development Disabilities Nurses Association.

Staff affirmed to DRI that they employed no other therapies for addressing the child’s self-abuse except for holding his hands. The staff assured DRI that one of the two staff members in the ward would hold his hands at all times. Upon later returning unannounced to the same room, DRI observed another teenage patient holding the child’s hands while the staff members were elsewhere. Another resident provided DRI with a photograph that shows the self-abusive teenager with his hands tied together with what appeared to be rope.

B. Segregation and Abuse of Children and Adults with Disabilities

Local organizations, with the assistance of UNICEF and international donors, have made important steps forward in promoting foster care, small group homes and day care centers to promote deinstitutionalization of children in Georgia.