DISABILITY RIGHTS DURING THE PANDEMIC

A global report on findings of the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor

Credits

© COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor 2020

Lead author: Dr. Ciara Siobhan Brennan

Editors: Steven Allen, Rachel Arnold, Ines Bulic Cojocariu, Dragana Ciric Milovanovic, Sándor Gurbai, Angélique Hardy, Melanie Kawano-Chiu, Natasa Kokic, Innocentia Mgijima-Konopi, Eric Rosenthal, and Elham Youssefian.

Design and accessibility by Stafford Tilley www.staffordtilley.co.uk

Disclaimer

This work may be freely disseminated or reproduced with attribution to the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor (COVID-19 DRM). The authors, editors and members of the Coordinating Group of the COVID-19 DRM accept no liability in any form arising from the contents of this publication.

Acknowledgements

The Coordinating Group of the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor (DRM) wishes to thank all those who responded to the COVID-19 DRM Survey, the organisations of persons with disabilities and the non-governmental organisations which disseminated the survey.

We especially thank Ms Catalina Devandas Aguilar, former U N Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Mr Dainius Pūras, former U N Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health and Ms Ikponwosa Ero, U N Independent Expert on the Enjoyment of Human Rights by Persons with Albinism for their endorsements of the COVID-19 DRM initiative. We also thank Dr Ciara Siobhan Brennan for leading the analysis of the responses to the survey.

The Coordinating Group of the COVID-19 DRM also wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following translators of the survey and web developers for their valuable contributions: Jonathan Center (Albanian – Shqip); Cicik Perkasa (Bahasa Indonesia); “Shunte Ki Pao??” Organisation (In English “Can You Hear?”) (Bangla); Aneta Genova, Vladimir Mirchev and Tsvetelina Marinova (Bulgarian); Natasa Kokic (Croatian, French); Ines Bulic Cojocariu (Croatian); Šárka Dušková (Czech, Slovak); Frank Sioen and Tina Sioen (Dutch); Laurence Le Blet, Carlota Gonzalez and Sarah Degée (French); Laura Partridge (French, German); Petra Flieger (German); Kamil Goungor (Greek); Erzsébet Oláh and Sándor Gurbai (Hungarian); A I F O – Italian Association Amici di Raoul Follereau (Italian); Laura Alčiauskaitė (Lithuanian); Elvin Sciberras from the Commission of the Rights of Persons with Disability – Malta (Maltese); Disability Holistic Development Service Organisation Nepal (DHD S O N) (Nepali); Regina Cohen and Mariana Seara (Portuguese); Ion Schidu and Valerian Mamaliga (Romanian); Alyona Khorol (Russian); Nina Portolan and Dragana Ciric Milovanovic (Serbian); Maroš Matiaško (Slovak); Polona Curk (Slovenian); Lisbet Brizuela and Ivonne Millan (Spanish); Girma Gadisa Tufa, Hari Tesfaye Kerga, Nahom Abraham Woldeabzghi and Imad Tune Abdulfetah (Amharic); Mai Mamoun Mubark Aman and Osman Eisa (Arabic); Zoltán Várady and András Váradi (web developers).

The Coordinating Group is thankful to Inclusion Europe for producing an Easy-To-Read version of the Executive Summary of the final report.

Contents

- Soundbites

- Acronyms

- Executive summary

- Part 1 Introduction

- Part 2 Methods

- Part 3 Inadequate measures to protect persons with disabilities in institutions

- 3.1 Failure to protect the lives, health and safety of persons with disabilities in institutions

- 3.2 Further deprivation of liberty

- 3.3 Measures to inform people in institutions about the state of emergency

- 3.4 Older persons with disabilities in institutions

- 3.5 Recommendations for Governments Related to Persons with Disabilities in Institutions

- Part 4 Significant and fatal breakdown of community supports

- Part 5 Disproportionate impact on underrepresented groups of persons with disabilities

- Part 6 Denial of access to healthcare

- Part 7 Conclusion

- Endnotes

- Glossary of terms

- Coordinating organisations

Soundbites

"The cost of living has gone up exponentially, but our benefits have not" - A female with disability, Canada

“Desde nuestra organizacion hemos elaborado una encuesta, en la evidenciamos que un alto porcentaje de familias tienen angustia, estres y una situación económica dificil, sin respuesta a la fecha del Estado” - An organisation of persons with disabilities, Colombia

“Persons with disabilities will suffer the most because most of their support interventions has been stopped” - An organisation of persons with disabilities, Tanzania

“Me preocupa el triage” - A female with disabilities, Mexico

“Nothing has been done with regards to inclusion of people living with albinism” - A male with albinism, Eswatini

“L’accès aux soins a été supprimé pour les malades chroniques et les personnes ayant des troubles psychosociaux. Les suivis ne sont plus assurés” - An organisation of persons with disabilities, France

“People in institutions are not receiving adequate assistance or access to medical supplies. Staffing is insufficient and at dangerous levels” - A female with disabilities, United States

“Én autizmussal élek, szociális munkás vagyok. Nem kaptam megfelelő védőeszközt a munkámhoz...” - A male with disabilities, Hungary

"Although the government has taken various steps regarding COVID-19, we do not see any clear steps being taken for the benefit of people with disabilities" - A male with disabilities, Bangladesh

“Ci hanno abbandonato” - A female with disabilities, Italy

“The government has supported virtually everyone else, and left people with disabilities to fend for themselves” - A female with disabilities, Australia

“Без рехабилитация, без разходки, без специализирана помощ…” - A family member of a person with disability, Bulgaria

“We have been forgotten about” - A female with disabilities, New Zealand

“Mental health services which are community based are not available, this put beneficiaries at risk of relapse” - An organisation of persons with disabilities, South Africa

“Mehr Arbeitslosigkeit, mehr Segregation durch (teil)Betreutes Wohnen: größere psychische Belastungen ebenda, mehr Ungleichheit im Bildungsbereich, weniger Informationen” - A person with disabilities, Austria

Acronyms

Acronym - Stands for

CEDAW - Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women

COVID-19 DRM - COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor

CRC - Convention on the Rights of the Child

CRPD - Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

DRF/DRAF - Disability Rights Fund/Disability Rights Advocacy Fund

DRI - Disability Rights International

ENIL - European Network on Independent Living

IDA - International Disability Alliance

IDDC - International Disability and Development Consortium

IMM - Independent Monitoring Mechanism

OPCAT - Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture

OPD/DPO - Organisation of Persons with Disabilities/ Disabled People’s Organisation

NHRI - National Human Rights Institution

NPM - National Preventive Mechanism, under the auspices of OPCAT

PPE - Personal protective equipment

SDGs - Sustainable Development Goals

UN - United Nations

WHO - World Health Organization

Executive summary

This report has one central purpose: To raise the alarm globally as to the catastrophic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on persons with disabilities worldwide and to catalyse urgent action in the weeks and months to come.

The report sets out the outcomes of a rapid human rights-based global monitoring initiative – the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor (COVID-DRM) – sponsored by a consortium of seven leading disability rights organisations, which took place between 20 April and 8 August this year. Through centring the testimonies of 2,152 respondents from 134 countries, predominantly from persons with disabilities themselves, the report draws the worrying conclusion that states have overwhelmingly failed to take sufficient measures to protect the rights of persons with disabilities in their responses to the pandemic.

Perhaps most troubling of all, it highlights that some states have actively pursued policies which result in wide-scale violations of the rights to life and health of persons with disabilities, as well as impacting on a wide range of other rights including the rights to liberty; freedom from torture, ill-treatment, exploitation, violence and abuse; the rights to independent living and inclusion in the community, and to inclusive education, among others. Such practices give rise to specific instances of discrimination on the basis of disability, and must be directly challenged and prevented.

Notably, these issues are not confined to developing countries alone. While the pandemic has strained public authorities in virtually every country, one significant finding of this study is that persons with disabilities report being left behind in countries regardless of their level of development, across both wealthy and developing states. In many cases, the disproportionate impact of the virus and state responses could have been predictable – and steps should have been taken to mitigate some of the worst effects. In some cases, the failure to act has had fatal consequences. In other cases, states have taken actions which cause further harm to persons with disabilities such as through denying access to basic and emergency health care, imposing dangerous lockdowns on overcrowded institutions, and through heavy-handed enforcement of public security measures.

One of the most common faults has been the failure to genuinely include persons with disabilities in the collective response – both at national and global levels. Policymakers at many levels appear to have reverted to treating persons with disabilities as objects of care or control, undermining many of the gains of recent years to enhance citizenship, rights, and inclusion. The testimonies collected throughout the initiative and presented in this report show that this is a faulty approach which runs counter to human rights advancement.

If we are to have any hope of bringing the pandemic under control, it is crucial that states ground their responses in human rights which are genuinely inclusive of all persons with disabilities.

The COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor (COVID-DRM)

As the novel Coronavirus started spreading around the globe at the beginning of 2020, disability rights organisations quickly began receiving ad hoc reports from persons with disabilities that problems were emerging. Worries were expressed about the possible implications of virus transmission in institutions, services to persons with disabilities were being strained, and people were experiencing increased difficulties in accessing general health care. The World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the virus outbreak had become a global pandemic on 11 March, following which unprecedented measures were rapidly adopted by states around the world to install lockdowns and ‘stay at home’ orders. Many undertook emergency measures to reorganise their health care systems, and the majority of states began closing schools, workplaces and large sections of their economies.

In March, the Validity Foundation proposed the creation of an international survey to collect information in real-time regarding the impact of the virus and state measures to respond to the pandemic on the human rights of persons with disabilities. A Coordinating Group was established,[1] formed of the representatives of seven organisations which advocate for the rights of persons with disabilities worldwide, who collectively developed the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor (COVID-DRM). A survey was designed to collect information about state measures to protect key rights guaranteed under the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Disabilities (CRPD). The questions focused on the rights to life, health, independent living, and inclusive education. Additional questions concerned measures taken to protect the rights of particularly marginalised populations of persons with disabilities including children, older persons, homeless persons, women and girls, as well those of persons with disabilities residing in institutions and in rural or remote settings.

Three versions of the survey were created, each targeting a distinct category of stakeholders:

- Persons with disabilities, family members and their representative organisations;

- Government representatives; and

- Independent human rights authorities including National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs), National Preventive Mechanisms (NPMs), and Independent Monitoring Mechanisms (IMMs) under Article 33(2) CRPD.

The survey was published in 25 languages on a specially-designed website – www.covid-drm.org – and was further disseminated throughout the Coordinating Group’s international networks. The website provided a summary of anonymised data concerning the numbers of responses received, their geographical distribution, and a selection of quotes throughout the period that the survey remained open. The Coordinating Group also undertook a number of targeted advocacy initiatives and presented preliminary findings at the opening session of the CRPD Committee’s resumed 23rd session which took place virtually on 17 August.

Overview of the report

The report is organised around four themes which emerged during the process of analysing responses received to the survey. These themes are:

- Inadequate measures to protect persons with disabilities in institutions

- Significant and fatal breakdown of community supports

- Disproportionate impact on underrepresented groups of persons with disabilities

- Denial of access to healthcare

Parts One and Two provide a detailed description of the approach taken in designing and disseminating the survey, including the approach and methods deployed. A human rights-based approach to research was consciously pursued throughout, while a mixed-methods analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data gave rise to four core themes which are explored below. The vast majority of responses came from persons with disabilities and their representative organisations, with the survey receiving over 3,000 separate pieces of written testimony, many of which described serious and life-threatening situations for persons with disabilities in 134 countries.

In contrast, and despite the determined efforts of the partners on the project, very few responses were received from governments and independent human rights authorities. This fact alone underlines one of the core conclusions of this study, namely that governments have yet to adopt truly inclusive responses to the pandemic – a situation which must change if our societies are to build back better. Although the study also sought information from NHRIs and other independent bodies about their efforts to monitor disability rights during the pandemic, very few actually responded to the survey, and those that did explained that their monitoring activities had been severely restricted. This raises concerns about a lack of independent human rights monitoring throughout the pandemic – strengthening the need for the present study.

The following four parts provide detailed analysis of the findings under four themes.

Part Three outlines the shocking situation for persons with disabilities who live in various types of institutions throughout the world, with hundreds of testimonies describing mass fatalities, a lack of preparedness to prevent virus transmission, and shocking accounts about the implications of total lockdowns on residents who were often denied even basic information about how to keep themselves safe.

The findings starkly confirm some of the worst fears of disability rights advocates as to the inherently dangerous nature of congregate settings at any time and point to a reckless disregard of policymakers to take protective measures. Institutionalisation itself is a human rights violation, and while all states which have ratified the CRPD are under an obligation to end this practice and promote independent living, the lack of progress in many countries prior to the pandemic inevitably subjected residents with disabilities to extreme risks.

In a number of countries, respondents pointed out that emergency health care was denied to adults and older persons in institutional settings, amounting to a grave violation of the rights to life and health. The CRPD Committee recently added its authority to this call by establishing a Working Group on Deinstitutionalisation in early September, to guide and push for rapid action by those states which maintain such residential facilities.[2]

Part Four looks at evidence suggesting a serious breakdown in provision of support for persons with disabilities in community settings, again underlying a lack of preparedness on the part of many states which left people isolated, without access to basic necessities such as food and nutrition, and forced to battle against significant barriers to receiving healthcare, even for those with long-term and chronic health conditions.

In-home services and personal assistance schemes were reportedly halted or severely curtailed in many countries, and while some governments took steps to provide emergency supplies to their populations during lockdowns, a number of respondents with disabilities pointed out that they could not access such schemes.

A large number of respondents raised concerns about the severe impacts of enforced periods of isolation on their mental health, though there were few avenues available to receive practical support, a situation which is likely to have enduring and long-term consequences.

Although there were some positive examples of governments beginning to provide information about the pandemic, this was far from consistent and many respondents reported a distinct lack of accessible information related to the pandemic and how to keep themselves safe. A worrying picture also emerged about the enforcement of curfews and other ‘stay at home’ orders on persons with disabilities, with numerous reports of violence, harassment, threats, and the imposition of disproportionate fines, as well as a number of tragic fatal incidents. It was reported in a number of countries that the only genuine community-based support was provided by volunteers and civil society organisations, in particular DPOs, with such responses rarely being sponsored by government authorities.

Part Five assesses the situation of underrepresented populations of persons with disabilities, who reported experiencing multiple forms discrimination and marginalisation, resulting in serious human rights violations. Underrepresented populations include women and girls with disabilities, homeless persons, children, older persons, those living in rural or remote areas, deaf or hard of hearing persons, persons with intellectual disabilities, persons with psychosocial disabilities, persons with deafblindness, and persons with autism.

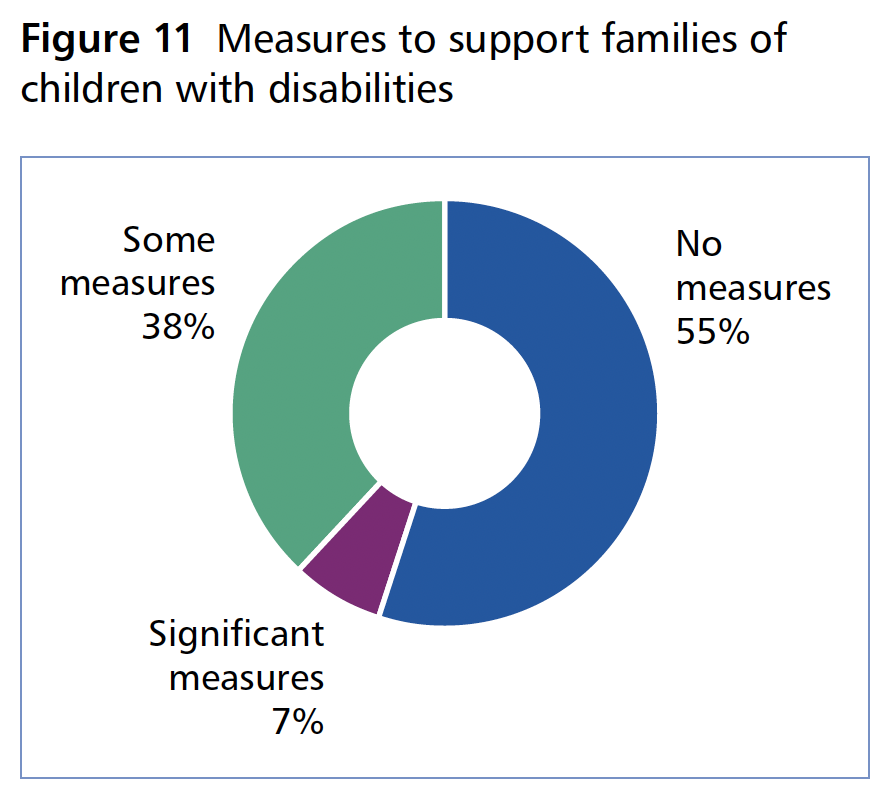

The majority of respondents reported that their governments had taken little or no action to protect the lives, health, and safety of children with disabilities, with concerns including the lack of provision of personal protective equipment (PPE), the withdrawal of the limited support provided to families, and the near-total exclusion of children with disabilities from education as schools were closed or adopted online teaching environments which were largely inaccessible. Separately, numerous reports suggested a dramatic increase in gender-based violence against women and girls with disabilities including rape, sexual assault, and harassment at the hands of enforcement authorities or family members.

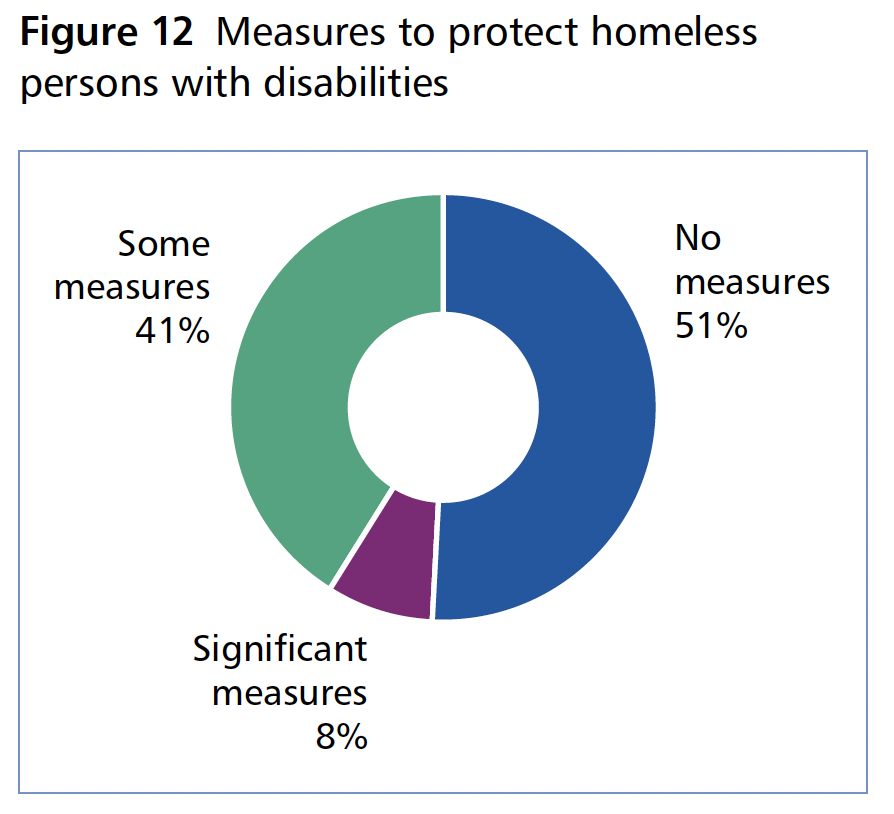

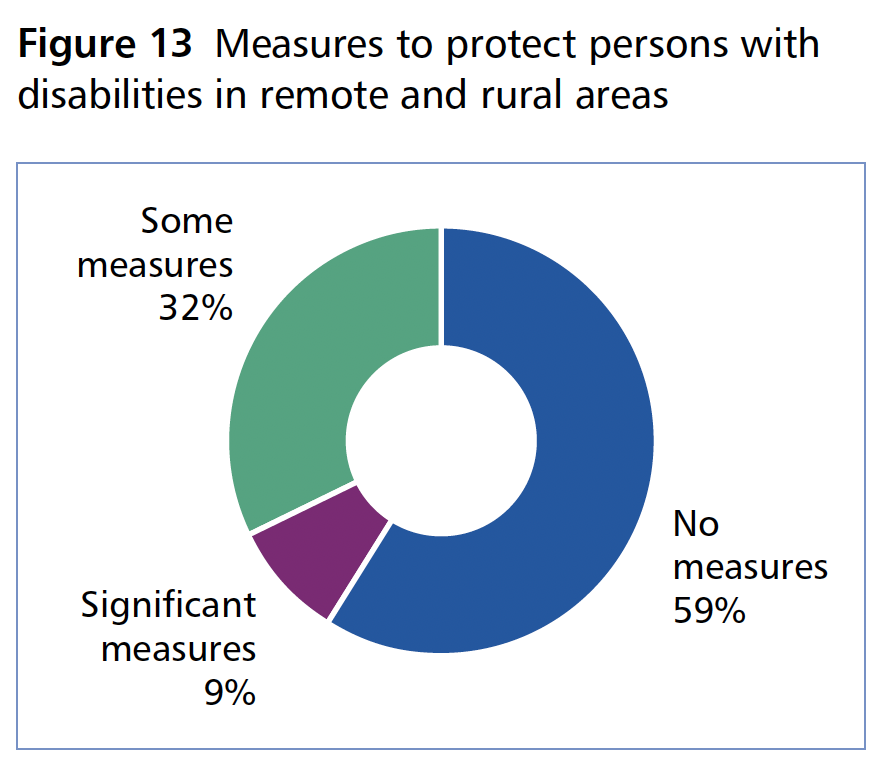

The survey results suggested that few governments had taken action to address the particular vulnerabilities of homeless persons with disabilities. While some governments did provide temporary forms of accommodation, in other cases policymakers opted to pursue misguided approaches such as rounding people up and placing them into group quarantine settings. Particular challenges were also reported in relation to people with disabilities living in rural and remote settings, both through the lack of availability of essential supplies and services, as well as the inability to access information. At a fundamental level, state responses to the pandemic lacked inclusiveness and often enhanced the exclusion already faced by multiply marginalised populations of persons with disabilities.

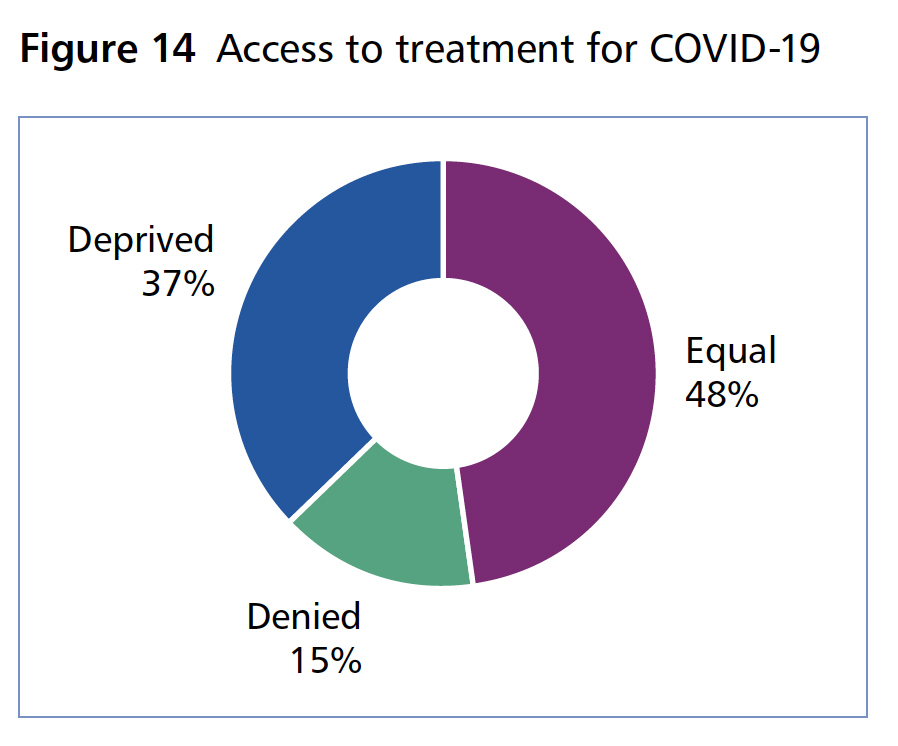

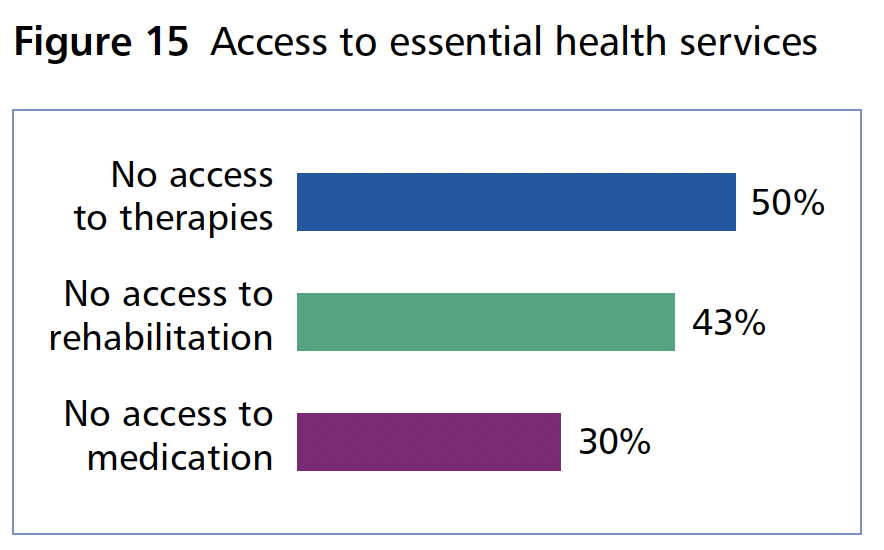

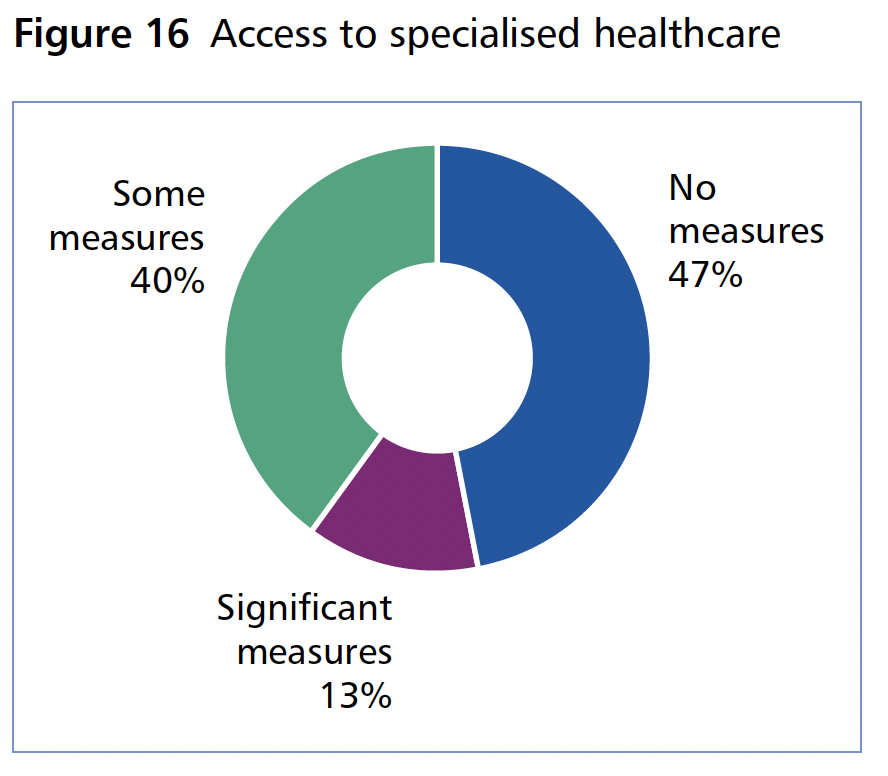

Part Six raises profound concerns about violations of the right to health for persons with disabilities, with numerous testimonies suggesting states had adopted triage policies or practices which directly or indirectly denied access to treatment on the basis of disability. While states were forced to take emergency measures to prioritise access to healthcare and many experienced unprecedented challenges in responding to the scale of need as the pandemic raged, discriminatory notions concerning disability resulted in life-threatening decisions to restrict or deny basic and emergency healthcare, including for those who had contracted COVID-19. The situation was reportedly compounded in countries without guaranteed universal healthcare, with numerous respondents reporting that the price of medicines and other treatments had soared, and that treatment for chronic and long-term health conditions had been stopped.

Conclusions and Recommendations

A pandemic is, by definition, a public health emergency of international concern which requires collective action and solidarity at all levels. Thus far, the Coronavirus pandemic has had a devastating impact on the rights of persons with disabilities. Recovery efforts will only be effective where they are genuinely inclusive and grounded in human rights. The testimonies collected throughout this study show just how precarious the situation is and that far greater efforts are needed to mitigate the disproportionate impacts of this emergency, including upon those who have traditionally been marginalised on multiple grounds.

As international efforts begin to coalesce around the principle of ‘Building Back Better’, the Coordinating Group of the COVID-DRM underline the crucial need to include persons with disabilities at all levels of planning and response. We must guard against disempowering notions that persons with disabilities be treated merely as recipients of aid. A sustainable response is possible where leaders with disabilities are acknowledged and become genuine partners in solving problems. The success or otherwise of the international community to tackle the pandemic will ultimately be judged on the extent to which the human rights and dignity of the most marginalised populations are proactively protected and where committed efforts are undertaken to learn lessons to build a better future.

In the rush to respond to the emergency, we must not lose sight of the need to build a sustainable and inclusive recovery process. The Sustainable Development Goals, while adopted far in advance of the pandemic, are more relevant than ever and should guide the collective efforts of public authorities, states, public and private donors as well as regional and international bodies such as the UN. Particular attention should be paid throughout to those at greatest risk of being left behind, including women and girls with disabilities, homeless persons, children, older persons, those living in rural or remote areas, deaf or hard of hearing persons, persons with intellectual disabilities, persons with psychosocial disabilities, persons with deafblindness, and persons with autism. It is also crucial that recovery efforts should not perpetuate pre-existing problems of discrimination and segregated structures of services, such as institutions and residential care for children and adults. Instead, recovery efforts should advance the goals of full rights protection and societal inclusion for all.

While there are many concerns, the report also highlights some promising practices that include persons with disabilities and/or their representative organisations in inclusive COVID-19 responses to the crisis from around the world. In some cases, these were organised and led by organisations of persons with disabilities to respond to clear gaps in state responses. They show that, through working with persons with disabilities, some of the most serious impacts of the pandemic can be mitigated. We urge decision-makers to support such important, community-level initiatives.

The following recommendations should guide immediate action:

- Ensure that all recovery efforts protect the rights to life, health, liberty, freedom from torture, ill-treatment, exploitation, violence and abuse, the rights to independent living and inclusion in the community, and to inclusive education, among others, for persons with disabilities without any discrimination on the basis of disability.

- Ensure that all persons with disabilities have immediate access to food, medicine, and other essential supplies.

- Ensure that persons with disabilities have equal access to basic, general, specialist, and emergency health care and that triage policies never discriminate on the basis of disability or impairment.

- Enact emergency deinstitutionalisation plans, as informed by persons with disabilities and their representative organisations, including adopting an immediate ban on institutional admissions during and beyond the pandemic, and the transfer of funding from institutions into community supports and services.

- Allocate adequate financial and human resources to ensure that persons with disabilities are not left behind in the COVID-19 response and in the recovery process.

- Provide economic, financial, and social support to ensure that persons with disabilities can enjoy their right to fully participate in the community on an equal basis with others, including having access to personal assistance at all times.

- Guarantee full participation, meaningful involvement, and leadership of persons with disabilities and their representative organisations at every stage of planning and decision-making processes in COVID-19 responses. Take steps to meaningfully involve children and young people with disabilities and their families and caregivers in the design and implementation of all policies in response to the pandemic.

- Ensure that emergency responses are disability-inclusive and take into account the diverse and individual needs of persons with disabilities, in particular those experiencing intersectional forms of discrimination and marginalisation such as women and girls with disabilities, persons living in rural or remote areas, deaf and hard of hearing persons, persons with deafblindness, persons with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities, and persons with autism.

- Prioritise inclusive education for children and young people with disabilities, especially children and young people living in congregate care. Ensure alternative education provision is accessible and provides reasonable accommodations based on the individual needs of children and young people with disabilities to guarantee their right to education.

- Prioritise the dissemination of comprehensive and accessible information in a variety of formats for persons with disabilities concerning the pandemic, response efforts, and public health information and guidance.

- Provide disability-awareness training for police and law enforcement authorities, and accountability for disproportionate enforcement of public health-related restrictions. Ensure access to justice for persons with disabilities who have experienced or are at risk of experiencing abuse, violence, or exploitation as a result of emergency measures.

Part 1 Introduction

In March 2020, as the COVID-19 virus began to spread, seven organisations focused on the rights of persons with disabilities, namely the Validity Foundation, the European Network on Independent Living, Disability Rights International, the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria, the International Disability Alliance, the International Disability and Development Consortium, and the sister organisations Disability Rights Fund and Disability Rights Advocacy Fund, joined together to develop the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor (DRM). The COVID-19 DRM survey provides an overview of the impact of the global pandemic on persons with disabilities around the world. With data amassed through a major international survey, the DRM was designed as a rapid, emergency monitoring of measures that were taken by governments to protect the rights of persons with disabilities.[3]

The COVID-19 DRM is committed to amplifying the voices of persons with disabilities, their representative organisations, and their family members as outlined in the findings of the survey to address the human rights violations persons with disabilities are experiencing around the world and ensure COVID-19 responses take into account the diverse and individual needs of persons with disabilities. As responses continue to evolve, it is important that they are rooted in a human rights-based approach proactively adopted by decision-makers, grounded in the human rights protections set out under international law, including the almost-universally adopted Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

To date, the COVID-19 DRM has widely disseminated the research findings. Three emergency statements were released while the data analysis was ongoing. The statements called on governments to take immediate action to:

- end the catastrophic human rights abuses in institutions; [4]

- end police violence and brutality;[5] and

- 3. ensure access to food, medication, and other essential supplies.[6]

An urgent action[7] was also initiated concerning the situation in residential institutions and calling for persons with disabilities to be immediately provided access to COVID-19 treatment in Romania. The COVID-19 DRM also had an impact at the international human rights level. At the opening of the 23rd session of the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, on 17 August 2020, the COVID-19 DRM shared the preliminary findings of the global survey.[8]

The questionnaire was available in 25 languages. It remained open for three months, from 20 April until 8 August 2020. During this period, there were 2,152 responses collected from people in 134 countries. The survey received an overwhelming number of responses from persons with disabilities (863), their representative organisations (525), and their family members (448).

Within the questionnaire responses respondents provided more than 3,000 written testimonies documenting the experiences of persons with disabilities and their family members during the pandemic. The qualitative and quantitative data provide in-depth, comprehensive insights into the experiences of persons with disabilities and the consequences of government actions or inactions on the rights of persons with disabilities.

This report presents the findings of the largest internationally comparable dataset, at the time of the publication, on how persons with disabilities worldwide were significantly and negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings reveal that governments around the world have failed to protect the numerous rights of persons with disabilities, namely the rights to life, health, liberty; freedom from torture, ill-treatment, exploitation, violence, and abuse; the rights to independent living and inclusion in the community; and the right to inclusive education. The report presents the findings in four thematic parts:

- Inadequate measures to protect persons with disabilities in institutions

- Significant and fatal breakdown of community supports

- Disproportionate impact on underrepresented groups of persons with disabilities

- Denial of access to healthcare

The report also highlights some promising practices from around the world that include persons with disabilities and/or their representative organisations in inclusive COVID-19 responses to the crisis. In the absence of inclusive government measures, persons with disabilities and their representative organisations led and advocated for more disability-inclusive responses to the pandemic.

An organisation of persons with disabilities in Belarus said:

“Where DPOs are strong, accessibility is higher than non-DPO locations. DPO leadership is very important, as proven in many areas.”

For decades persons with disabilities and their representative organisations have effectively advocated for and performed crucial developmental and humanitarian functions on every continent and region of the world, often under challenging conditions. The COVID-19 DRM calls on duty-bearers and signatories of the CRPD to remember their commitment to the inclusion of persons with disabilities and their representative organisations in any and all government responses to COVID-19. By definition, there can be no inclusive response to COVID-19 without the involvement of persons with disabilities and their representative organisations. Persons with disabilities and their representative organisations are critical in developing more inclusive COVID-19 responses and must have greater recognition and support from governments as well as decision-making authority.

Part 2 Methods

On April 20, 2020, the COVID-19 DRM launched a global survey to conduct rapid independent monitoring of state measures concerning persons with disabilities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey gathered quantitative and qualitative information (i) on the experiences of persons with disabilities, and (ii) on how States are responding to states of emergency situations in relation to this specific population. The survey was designed to use triangulation methodology in order to be able to collect and compare data from different stakeholders:

- from governments

- from national human rights monitoring mechanisms, and

- from persons with disabilities and their representative organisations.

2.1 A human rights-based approach

The COVID-19 DRM survey applied a human rights-based approach to data collection, data analysis, and dissemination of the findings. Participation is central to a human rights-based approach.9 The survey was designed to maximise the participation of persons with disabilities and their representative organisations from around the world.

The following tactics were used to garner equal responses from the three main stakeholder groups (persons with disabilities, governments, and national human rights institutes) and collect information:

- Multiple forms of survey – The questionnaire was available online through the COVID-19 DRM website for respondents who had access to the internet. Print versions of the survey were also provided for those with less reliable access to the internet. When responses to the survey were received in a Word document, a member of the COVID-19 DRM Coordinating Group entered the responses into the online survey and deleted the original Word document in line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- Availability of survey in over two dozen languages – The survey was available in 25 languages in total, including Albanian, Amharic, Arabic, Bangla, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Indonesia Bahasa, Italian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Nepali, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, and Spanish.

- Support to survey takers and distributors – A web-based dashboard contained guidelines for the dissemination[10] of the survey, which explained the aims and objectives of the study in the same 25 languages listed above, to ensure a consistent understanding of the purpose of the survey and the use of the data collected.

- Extensive dissemination to the public – The survey was sent out via email, sometimes on a weekly basis, and discussed on webinars with the global and regional networks of each Coordinating Group member. Social media campaigns were also launched via Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp.

- Targeted sampling to key stakeholder groups – The members of the Coordinating Group also targeted specific geographical regions, including Asia, Eastern Europe, and Oceania. Examples of targeted outreach include outreach by DRF/DRAF to its grantee networks in 32 countries where its grantmaking is active. ENIL shared the survey among its members in the Council of Europe area, focusing on countries in Western and Southern Europe. They also shared the survey among EU-level networks representing persons with disabilities and others, such as Equinet, which brings together Europe’s equality bodies. ENIL, Validity, and DRI also held a webinar on Emergency Deinstitutionalisation on 11 June 2020 and presented the survey to over 150 attendees.[11] Additionally, DRI sent the survey to approximately 70 persons from Mexico and Guatemala, including people with disabilities, mental health users, families, activists, and professionals on the ground, as well as to 13 Mexican government authorities, including local and federal authorities, the National Human Rights Commission, the Ministry of Health, the Federal Psychiatric Care Services, the National System for the Integral Development of the Family, and the Undersecretary of Prevention and Health Promotion from the Ministry of Health. Validity also undertook direct targeting of key stakeholders in Hungary, Romania, the Republic of Moldova and Russia, including through sharing the survey with national organisations of persons with disabilities and state authorities, as well as following up individually by phone and email.

- Accompaniment of human rights advocates to potential survey respondents – Graduate students at the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria administered the survey to individual respondents.

The data was disaggregated by key characteristics identified in international human rights law. The survey contained closed and open-ended questions that aimed to gather data about what States are doing to protect the core rights of persons with disabilities. These core rights included the right to life, the right to access healthcare, the right to live independently in the community, and the right to access services. To disaggregate the data, questions requested personal data, such as sex, country of residence, and disability category. However, respondents had the options to both withhold personal information and to remain anonymous.

Transparency was another key rights-based consideration when collecting data for the DRM survey. The survey findings were made publicly available on the COVID-19 DRM website. The website contains a dashboard that provides information about the number of responses from each country, selected, anonymous quotes[12] from respondents from around the world, and a weekly summary of the findings[13]. The identities of all respondents are protected. All identifying details have been removed from the data before it was published. In addition, all data collected was stored and managed in line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

2.2 Data analysis

Mixed-methods data analysis was used to analyse the data through an inductive research approach.[14] The survey contained open-ended and closed questions. The combination of qualitative and quantitative data provided a nuanced, in-depth insight into the experiences of persons with disabilities, and state measures to protect the rights of persons with disabilities during the pandemic. The quantitative data was analysed in Microsoft Excel. In addition to responding to the quantitative questions, most participants chose to provide several written testimonies in the open-ended questions. The survey received more than 3,000 written testimonies. They varied in length from a short sentence to long paragraphs. Prior to content analysis, testimonies in one of the 24 non-English languages listed above were translated into English using Google Translate. The testimonies were coded and thematically analysed. The key themes that emerged were: access to healthcare, access to food and essential supplies, conditions in institutions, and access to community support and services. These themes are discussed in detail in the findings section. The qualitative data was used to explore the meaning of the quantitative data in more detail. The qualitative data captured the voices of the respondents to the study.

2.3 Limitations

The survey was designed as a rapid response to an emergency situation that arose from the COVID-19 pandemic. The methodology utilised was appropriate and proportionate to the objectives of the COVID-19 DRM. However, there were several limitations that arose as a result of the quick turnaround of the survey design. Firstly, the survey was available neither in an easy-to-read format nor any sign language. Secondly, the survey was available online through the Disability Rights Monitor website, which limited the responses to persons who have online access. Thirdly, the responses were not equally representative of various regions of the world. Despite efforts to translate the survey and dissemination guidance into different languages, there was a low response rate from Arabic-speaking countries and Russian-speaking countries. Response rates were low in many Asian countries as well, but this may have been a result of the unavailability of the survey in major Asian languages. Efforts to mitigate these limitations included the availability of a print version of the survey, additional outreach by the Coordinating Group members to their respective networks, webinars with government officials and national human rights institutes, and an extension of the survey closing deadline by three weeks.

Fourthly, unequal response rates from the three stakeholder groups – persons with disabilities, governments, and national human rights institutes – were also a limitation. The survey was initially intended to triangulate the data from the three stakeholder groups. However, this was not possible given the low response rates from governments and human rights monitoring mechanisms. Instead, online research and third-party documentation were the main methods of data verification. This included documentation through media accounts, national human rights or ombudsman reports, or networks of organisations of persons with disabilities.

Fifthly, given the specialised nature of the topics covered in the questionnaire, respondents had the option to select “not my area of expertise” as a response to the closed-ended questions. These responses were treated as missing data and were excluded from the data analysis. While this is a limitation, it allowed the survey to cover a wide range of specialised topics. The final figures in the findings section only include those in which respondents chose another option.

Lastly, several of the open-ended questions were removed from the survey while it was still active. The decision to remove these open-ended questions was made to reduce the length of the survey.

2.4 Responses

The survey received 2,152 responses from 134 countries between April 20, and August 8, 2020. Despite the best efforts of the COVID-19 DRM to disseminate the survey among governments and human rights institutions, the survey received a very low number of responses from these stakeholders (26 governments and 12 human rights institutions). However, the survey received an overwhelming number of responses (2,112) from persons with disabilities, their representative organisations, and family members, making it the largest internationally comparable dataset on the experiences of persons with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

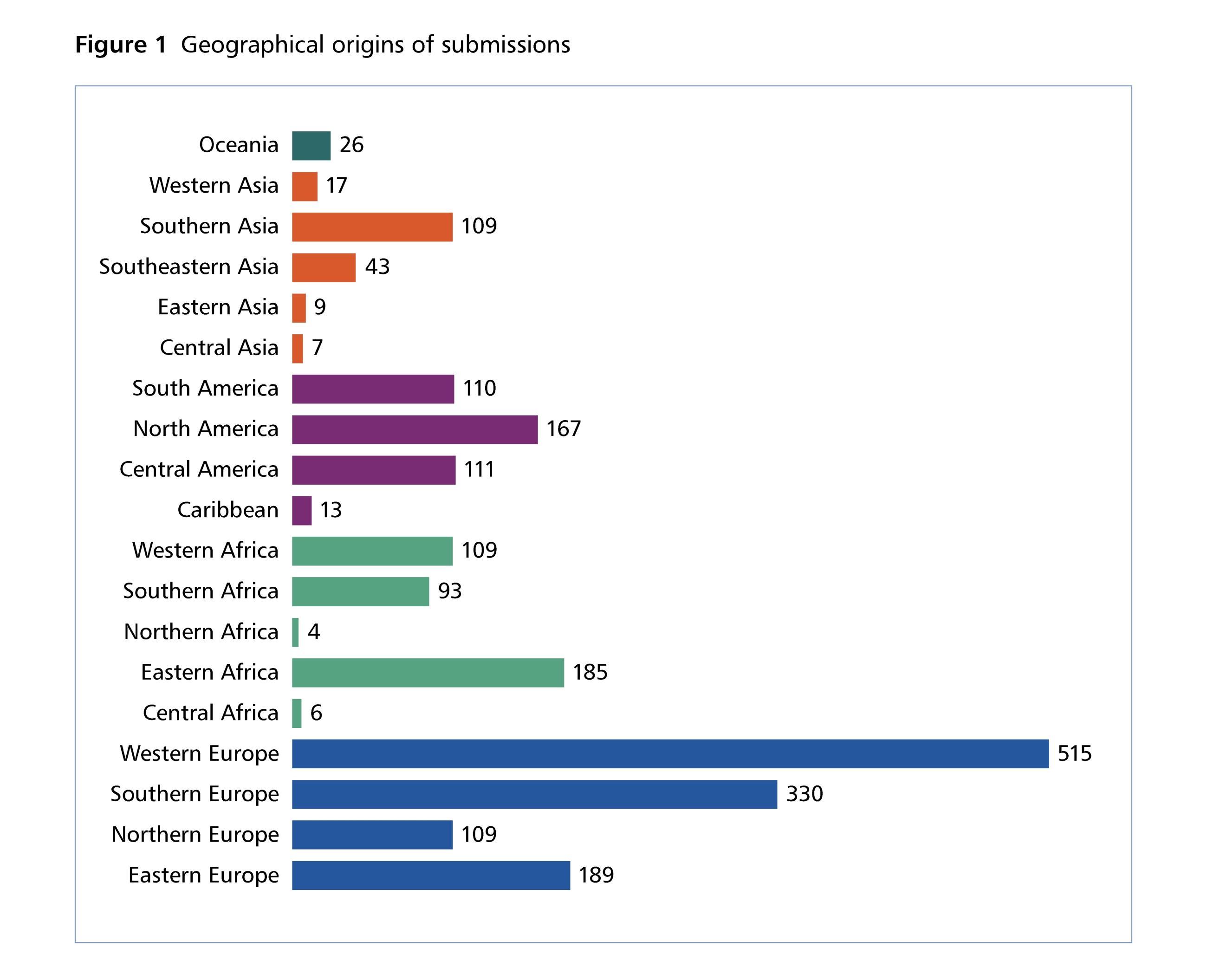

Figure 1 Geographical origins of submissions

The countries with the highest number of responses, listed below in Table 1, were Germany (225), Italy (130), and France (130). The United States was the North American country with the highest number of responses (94). South Africa was the African country with the highest number of responses (83). Mexico had the highest responses (73) from Central and South America. India had the highest number of respondents (50) in Asia.

2.5 Participants

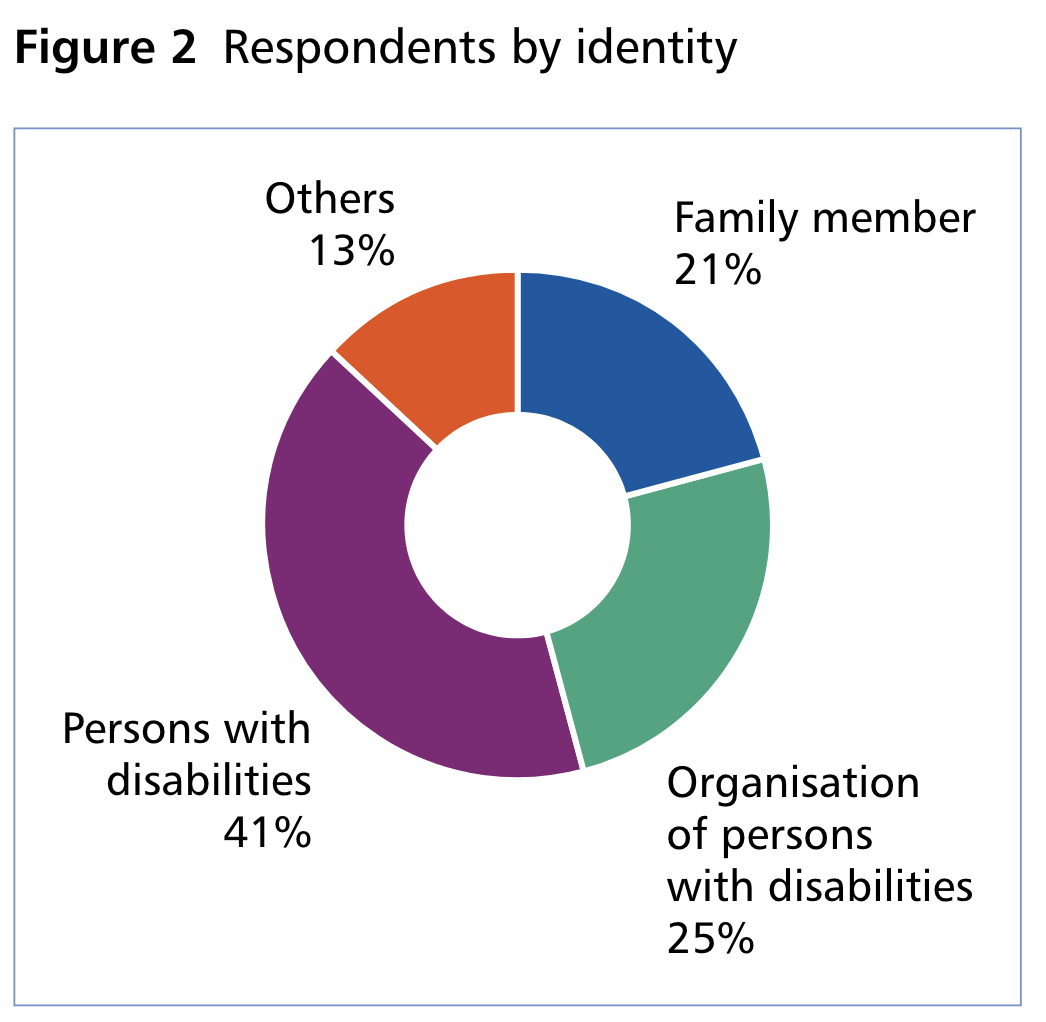

The majority of respondents (1,325) identified as female, 695 identified as male, and 92 identified as others or did not disclose. Most respondents, as shown in Figure 2, were persons with disabilities (863), the next largest group of respondents were organisations of persons with disabilities (525), followed by family members (448), and others (276). The other category included NGOs, persons working in services for persons with disabilities, and persons working in institutions for persons with disabilities.

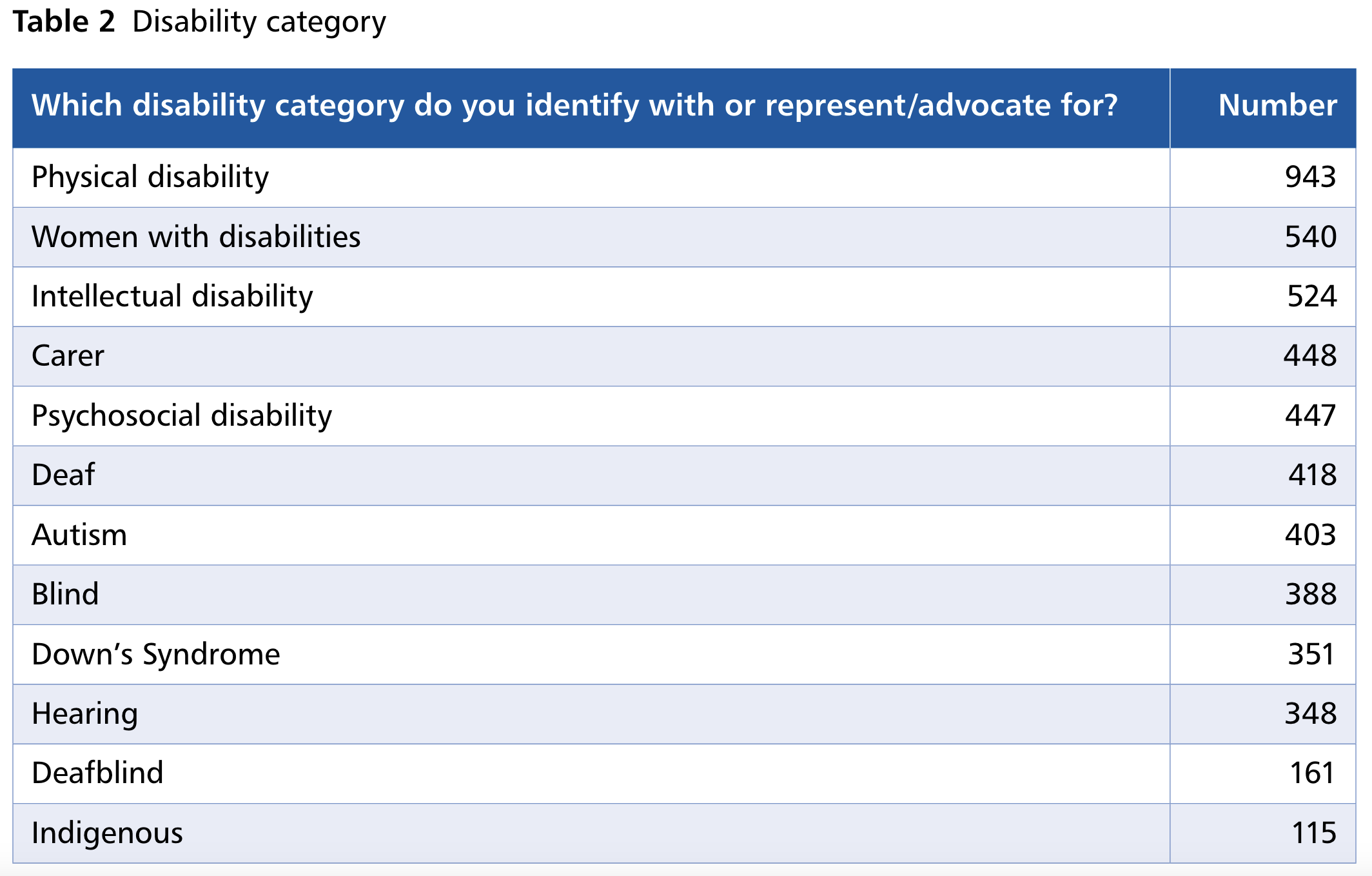

The respondents represented a diverse range of constituencies. The largest constituency was persons with physical disabilities (943), followed by women with disabilities (540), and persons with intellectual disability (524), as outlined in Table 2.

Figure 2 Respondents by identity

Table 2 Disability Category

Part 3 Inadequate measures to protect persons with disabilities in institutions

The findings of the COVID-19 DRM survey suggest that governments around the world have failed to protect the right to life of persons with disabilities in institutions during the pandemic. While the institutionalisation of persons with disabilities is in itself a violation of human rights, the 329 written testimonies from 50 countries demonstrate how the emergency measures that were taken by governments to control the spread of COVID-19 have exacerbated existing human rights abuses and failed to prevent further human rights abuses. These measures included the denial of access to healthcare, bans on visitors, and isolating residents when there was an outbreak of COVID-19.

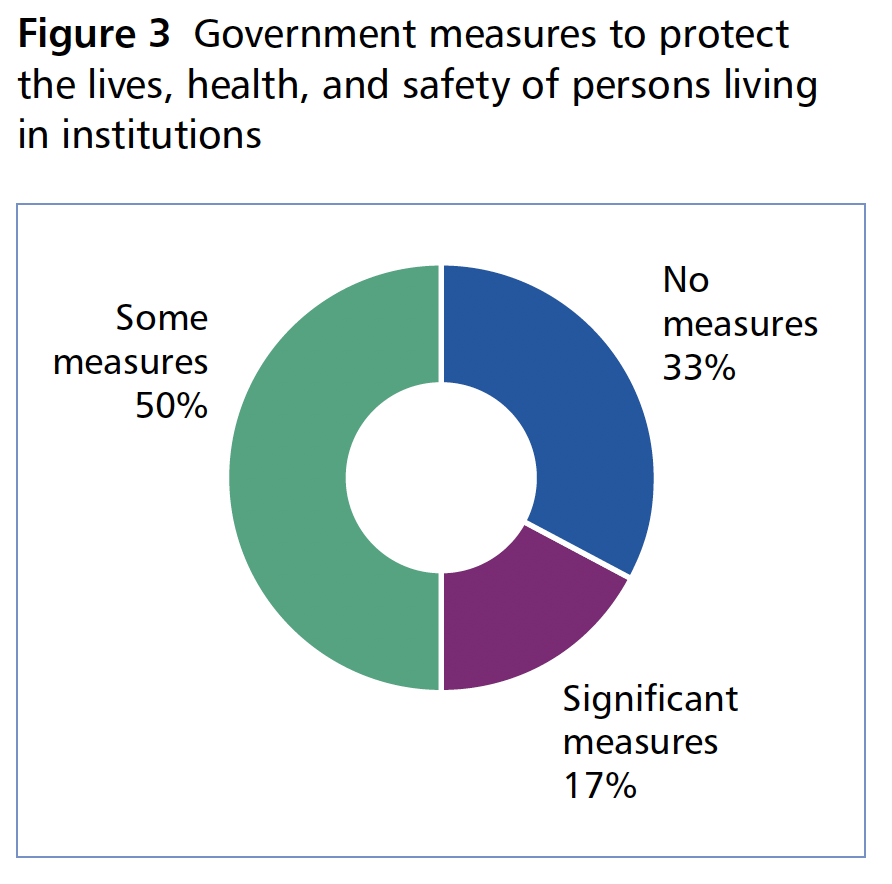

The highest number of these testimonies came from high-income countries including Germany, Austria, France, and Canada. They reveal grave and systemic violations of fundamental freedoms and human rights of persons with disabilities detained in large- and small-scale institutions, which have become the epicentre of COVID-19 infections and deaths. These institutions include group homes, psychiatric hospitals, retirement homes for older persons with disabilities, residential schools for children, and other residential settings where persons with disabilities are detained against their will. Congregate living arrangements within institutions are inherently more dangerous as infectious diseases can quickly spread without proper and swift precautions. Thirty-three percent of respondents said that governments took no measures to protect the lives, health, and safety of persons with disabilities living in institutions, as shown in Figure 3 below.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 within institutions was foreseeable, and states should have taken steps to protect the right to life for persons with disabilities.

Figure 3 Government measures to protect the lives, health, and safety of persons living in institutions

3.1 Failure to protect the lives, health and safety of persons with disabilities in institutions

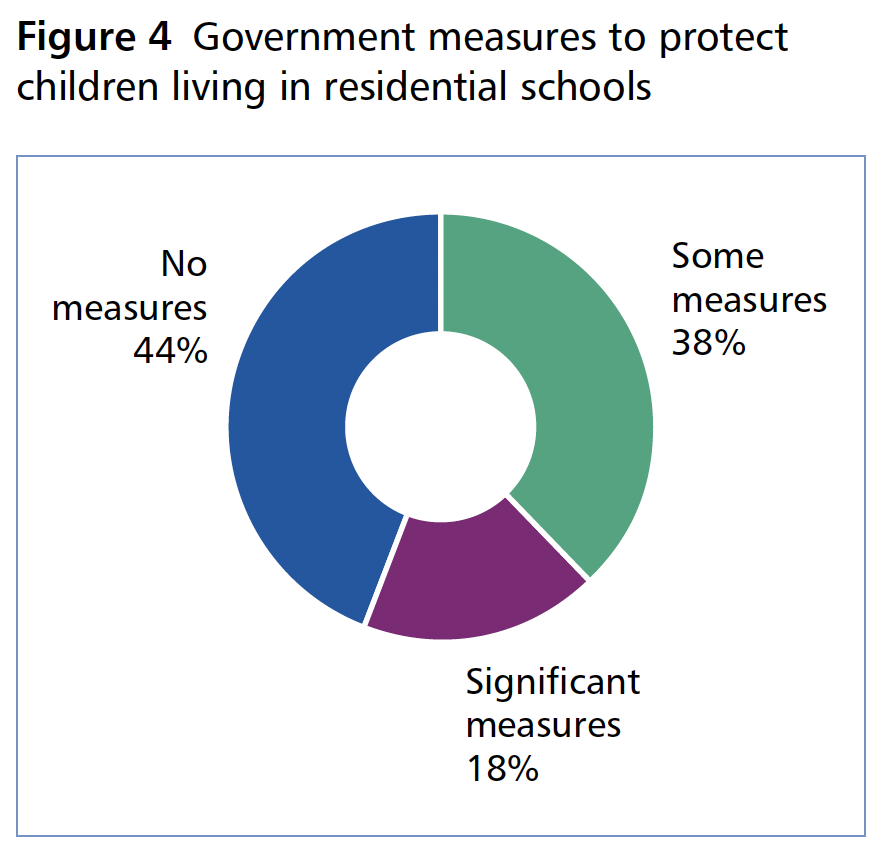

The survey findings shed light on the deadly conditions that resulted in the high death rates within large-scale and small-scale institutions. As shown in Figure 4 below, of those who answered, 44% (486) of respondents said that their government took no measures to protect children with disabilities in residential schools. Thirty-three percent (476) of the respondents who knew about the situation in institutions said that their government took no measures to protect the lives, health, and safety of persons with disabilities in institutions.

Figure 4 Government measures to protect children living in residential schools

The written testimonies provide a shocking insight into the situation of persons with disabilities in institutions. The survey received an overwhelming number of testimonies from around the world confirming that governments have not taken sufficient steps to safeguard the right to access food, basic medical supplies, personal protective equipment, or measures (such as social distancing) to minimise infections and deaths in institutions. A respondent with disabilities described the conditions inside the Herron residence in Quebec: The other residents were malnourished, dehydrated, and severely neglected. The institution was “dangerously understaffed. There were people dead in their beds, others laying on the floor and some others with three layers of diapers and dehydrated.”

The survey received more than 60 written testimonies that governments failed to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and adequate sanitation in institutions. The countries with the most written testimonies about the lack of PPE and cleanliness in institutions were the USA, the UK, Canada, Ireland, and South Africa. Written testimonies from people who were inside the institutions confirmed that there was a lack of access to PPE. For instance, a staff member from a Moldovan institution said that they had to buy their own PPE, without reimbursement from either the institution or the government.

There were also complaints of understaffing in institutions and of inadequately trained staff. Moreover, respondents complained that staff was transferred from one institution to another, allowing for the further spread of infection. There were complaints from around the world that governments did not act quickly enough to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks in institutions, and when measures were taken, it was already too late. Furthermore, if measures were taken, they were usually initiated by the institution, not the government. As a result, some respondents feared that the institutions had too much autonomy to decide the fate of the residents.

Promising example: provision of PPE in Palestine

There were also examples of DPOs, NGOs, and UN agencies providing PPE and hand sanitisation in institutions. For instance, a Palestinian respondent said that PPE was not provided “directly by the government, but by International Organisations, such as UNICEF and some national NGOs.” There was a joint strategy of the humanitarian community, including UN agencies, and NGOs, and the Palestinian government to respond to immediate humanitarian consequences of the pandemic.[15]

3.2 Further deprivation of liberty

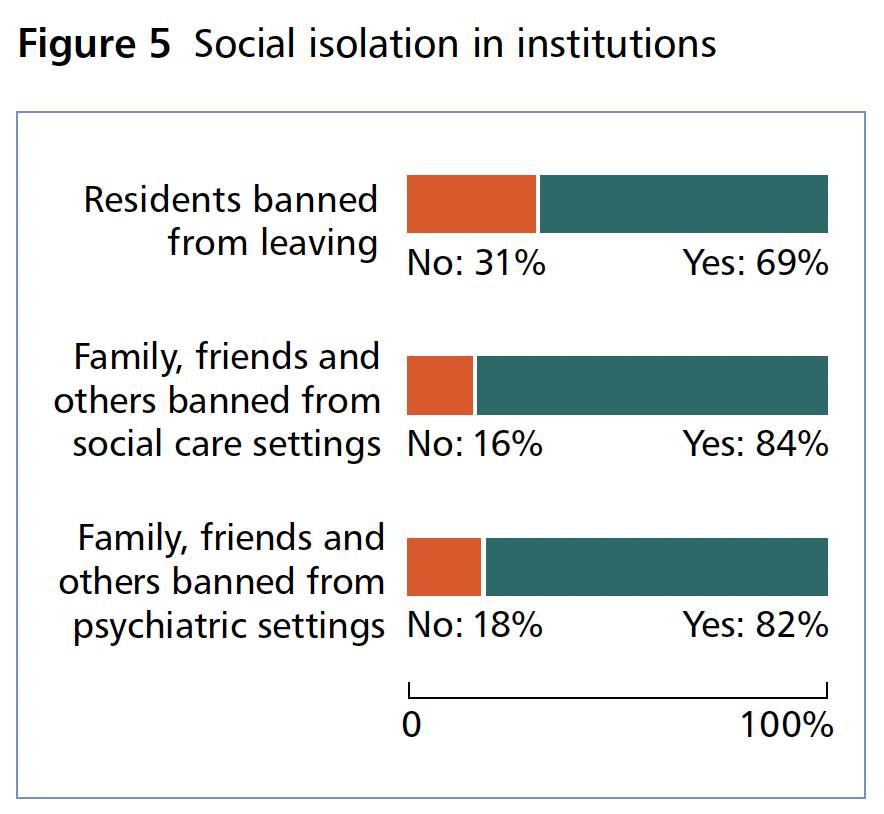

While institutions have always deprived residents of their liberty, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the situation even worse. Institutions around the world were cut off from the rest of society, without any monitoring mechanisms in place. Of the measures that were taken by governments, some of these included a ban on visitors and a ban on residents leaving. Of those who knew about the situation, the majority, 69% (819), said that persons with disabilities were restricted or banned from leaving the institutions (refer to Figure 5 on the right). A further 84% (1,172) said that the government had banned, or restricted visits from family, friends or others in social care settings, and 82% (984) of those who knew about the situation in psychiatric health facilities said that their government had banned visits.

Figure 5 Social isolation in institutions

Family members of persons with disabilities and organisations of persons with disabilities expressed grave concerns for their family members’ safety and wellbeing within institutions. While institutions were closed to prevent the spread of infection, there were fears that additional human rights abuses would occur behind closed doors, in the absence of monitoring mechanisms or family visits to institutions. A Bulgarian organisation of persons with disabilities feared that the measures that were taken to “prevent infection, but it is also a measure that could can lead to a lack of care, lack of transparency and concealment of dangerous abuses.” This sentiment was echoed around the world. In Guatemala, there were concerns for the three-hundred persons with disabilities who were sealed into the Federico Mora psychiatric facility without social distancing or access to hospital care.

Authorities have denied access to independent human rights authorities to monitor the health and safety of detainees.[16] A Greek organisation of persons with disabilities described the psychiatric institutions as “hermetically sealed with more absolute restrictions than before, with no possibility of visits, with no advocacy services and with no independent monitoring.”

Respondents were particularly concerned about the mental health of the residents. For instance, a German respondent feared that “the measures may help to prevent infection from COVID-19. But the psychosocial impact on people with disabilities cannot be underestimated.”

Respondents also feared for the mental health of children with disabilities in institutions.

A person with disabilities in Belgium said:

“From what I know, children in institutions are strictly confined, can no longer have contact with their families. They are really imprisoned while the providers bring the virus. Very significant mental consequences.”

The survey received written testimonies from staff and medics who had been inside institutions. These testimonies confirmed the fears of family members and organisations of persons with disabilities. Respondents who had been inside institutions during the pandemic reported that residents were overmedicated, sedated, or locked up. This situation is having a devastating effect on the mental health of the residents. An organisation of persons with disabilities from Andorra reported that “self-harm has occurred and the solution by the institution has been overmedication.”

Promising example: Twenty-four hour helpline in Moldova

A Moldovan organisation for persons with disabilities provides a 24/7 complaints mechanism helpline for persons with disabilities living in Moldovan institutions. Mobile phones were provided for self-advocates in institutions for calls in case of rights violations.[17]

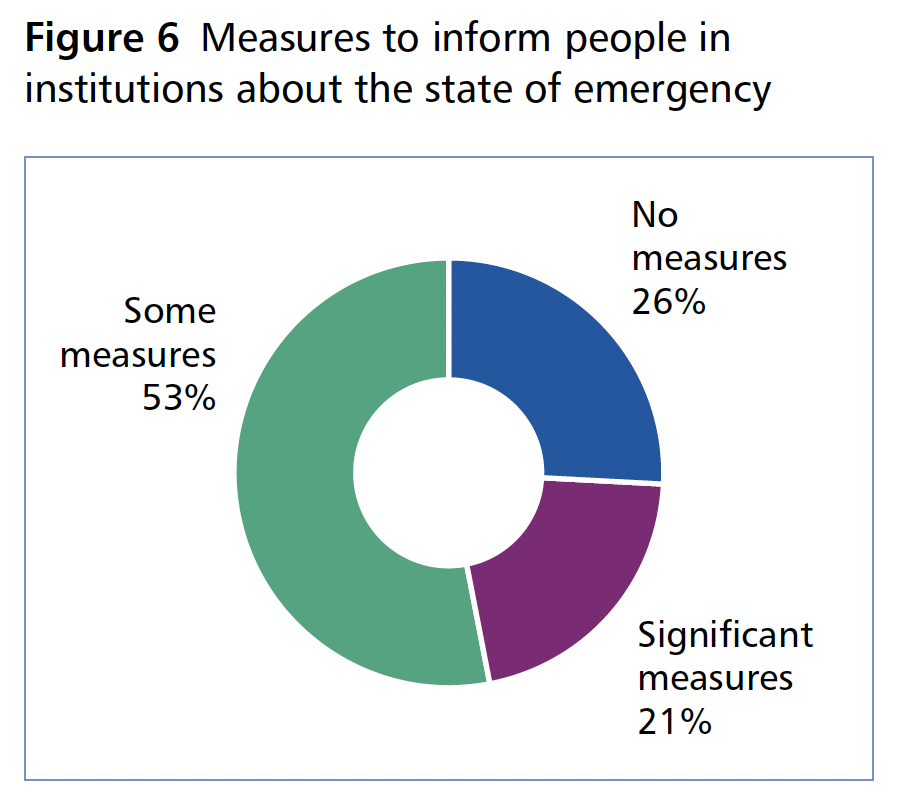

3.3 Measures to inform people in institutions about the state of emergency

There were reports that people living in institutions did not receive information about the pandemic and the emergency measures that were put in place by their governments. For instance, 26% (322) of respondents said that no measures were taken to inform persons with disabilities living in institutions about the state of emergency, including the bans and restrictions on visitors (refer to Figure 6 overleaf for additional responses). Many respondents were worried that persons with disabilities in institutions were cut off from society, without any knowledge of the state of emergency. They were concerned that persons living in institutions were not provided with adequate information to protect themselves from COVID-19.

An organisation of persons with disabilities in India said:

“A few things have been put up online at relevant government portals but most persons with disabilities have no access to these staying in institutions. Perhaps they don’t even know what is going on outside!!”

Promising example: Easy-to-read material made available in Serbia[18]

With the support of UNICEF, Mental Disability Rights Initiative of Serbia produced an Easy-to-read material which was distributed to people with disabilities in residential institutions and in the community

Figure 6 Measures to inform people in institutions about the state of emergency

3.4 Older persons with disabilities in institutions

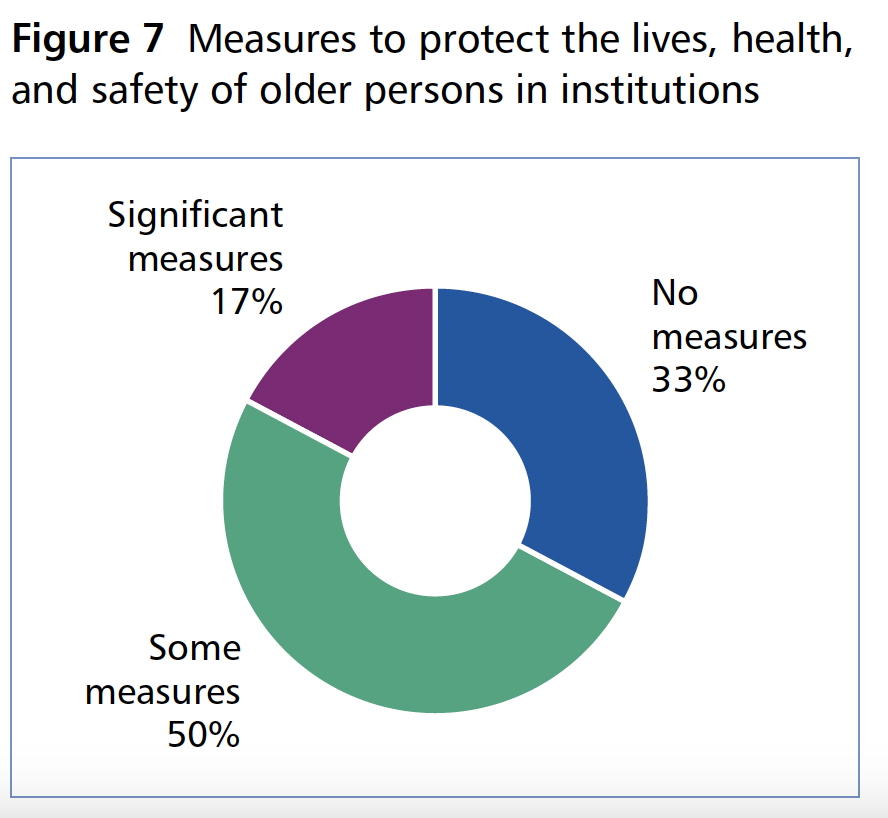

One-third (506) of the respondents who knew about the situation said that their government took no measures to protect the life, health, and safety of older persons (refer to Figure 7 on the right for additional responses). Of those who said that some measures were taken, many went on to explain that these measures were problematic, including bans on visits from family members, friends, and human rights monitors. Respondents were concerned for the effects that the isolation was having on the mental health of older persons in institutions.

A person with disabilities in Italy said:

“Many people didn’t even have an explanation as to why they couldn’t see their families anymore. Many older people thought they were abandoned and left to die.”

Testimonies criticised governments for not acting quickly enough to protect older persons in residential settings from the spread of the virus. For instance, an Irish respondent with disabilities said that “the measures taken to protect persons in institutions was a bit late coming, almost an afterthought.” Respondents also complained that their governments took general measures that did not ensure the protection and inclusion of older persons with disabilities. A Haitian organisation of persons with disabilities explained that “no specific measures have been taken in favour of older persons with disabilities.”

Figure 7 Measures to protect the lives, health, and safety of older persons in institutions

Promising example: Sanitisation efforts in Sudan

There were several promising examples, where governments prioritised the health and safety of older persons with disabilities in institutions. Such measures included access to PPE, social distancing, as well as frequent testing for COVID-19. The Sudanese government was praised for their efforts to sanitise residential homes for older persons with disabilities. Sudanese “NGOs, in collaboration with government agencies, conducted awareness-raising sessions, about COVID-19 and how to stay safe, distributed hand sanitizers, and conducted sanitisation rounds of institutions for older persons with disability.”

3.5 Recommendations for Governments Related to Persons with Disabilities in Institutions

In accordance with their obligations under international law, particularly the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the COVID-19 DRM calls on governments, funders, and global actors to take the following emergency response to avoid further catastrophe:

- Develop an emergency deinstitutionalisation plan in line with Article 19 of the CRPD and General Comment No. 5: Right to independent living (2017) of the CRPD Committee.[19]

- Implement an immediate no-admissions policy to large- and small-scale institutions.

- Closely monitor the situation in institutions and release data and information on the number of infections and fatalities in institutions.

- Guarantee immediate, unfettered access to independent national human rights authorities, including NHRIs and NPMs, to all institutions, ensuring safety protocols and procedures are in place to enable independent monitoring and direct communication between monitors and residents.

- Provide immediate access to food, PPE, social distancing measures, and appropriately trained staff.

- Provide accessible information in multiple formats about the state of emergency.

- Ensure full access to healthcare on an equal basis with other citizens.

- Implement immediate measures to ensure that residents can contact law enforcement and complaints mechanisms, and to ensure contact with family and friends.

- Ensure that persons within institutions have access to mental health supports and services.

- Prevent family separation and institutionalisation of children (or parents) due to COVID-19 pandemic.

The DRM also calls on governments to take the following longer-term steps to avoid future human rights emergencies:

- Actively involve persons with disabilities and their representative organisations, and civil society, in planning the recovery process and emergency deinstitutionalisation plans.

- Allocate adequate financial and human resources to support the transition from institutions to the community, in line with Article 19 of the CRPD.

Part 4 Significant and fatal breakdown of community supports

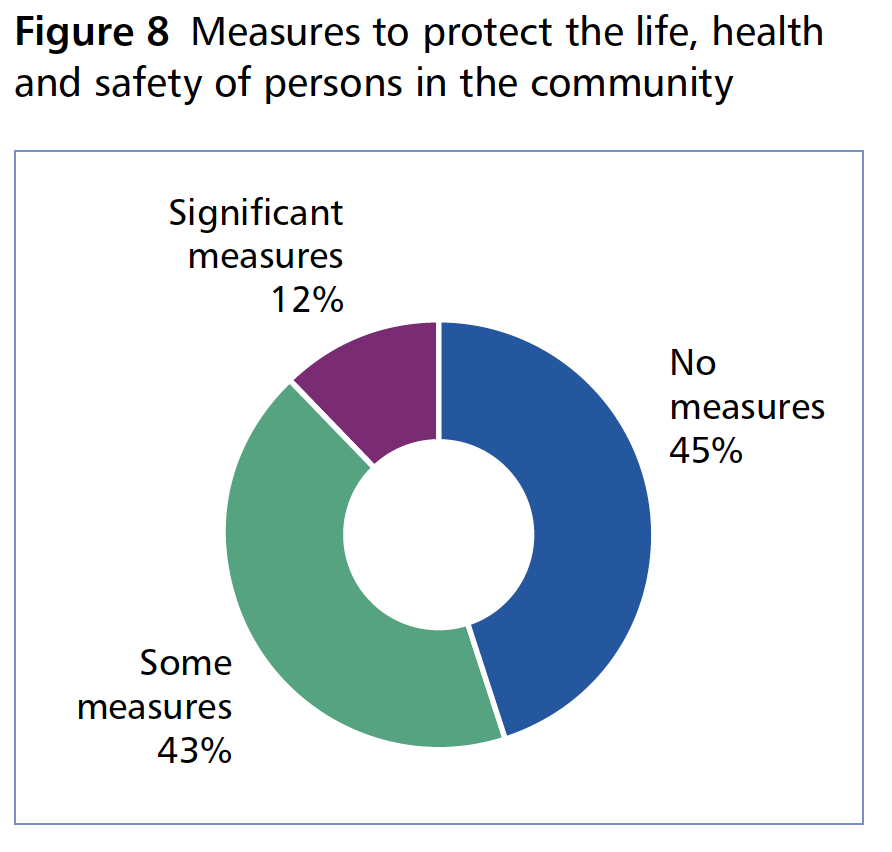

Forty-five percent (777) of participants said that their government took no measures to protect the life, health, and safety of persons with disabilities living in the community (refer to Figure 8 below for additional responses). Many persons with disabilities living in the community said that they were abandoned by the government and trapped at home, with no means to access food, medicine, or other basic supplies. Respondents from countries with particularly strict curfews were at increased risk of police harassment, intimidation, and violence.

Figure 8 Measures to protect the life, health and safety of persons in the community

4.1 Breakdown of community supports

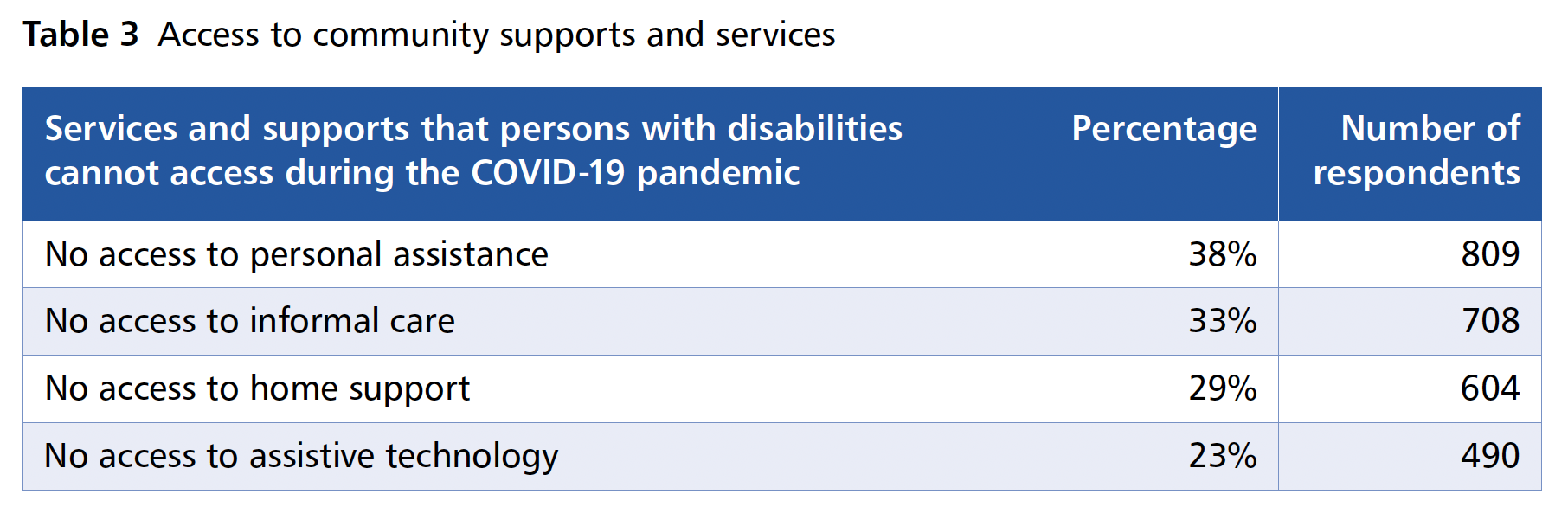

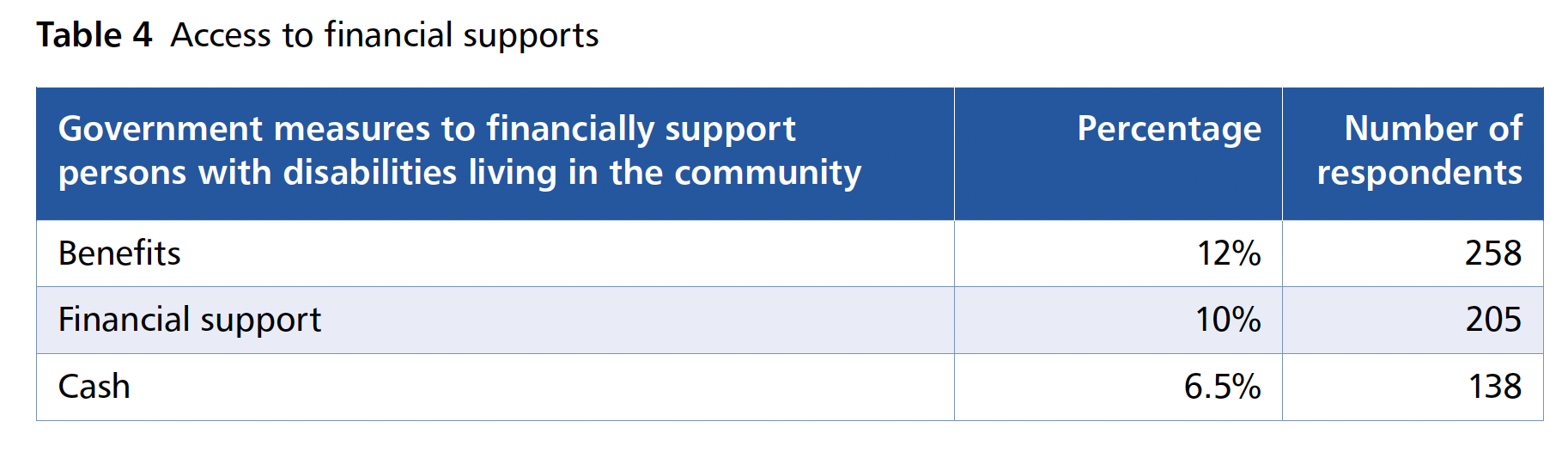

Many of the essential services that persons with disabilities rely on to live independently in the community were not available during the pandemic. For example, as outlined in Table 3 below, 38% (809) of the survey respondents said that persons with disabilities did not have access to personal assistance. Thirty-three percent (708) said that persons with disabilities did not have access to informal care. A further 23% (490) said that persons with disabilities did not have access to assistive technologies.

A very small minority of respondents reported any financial assistance from their governments during the pandemic, as outlined in Table 4 below. Only 6.5% (138) of respondents reported that their governments provided cash as a social protection measure to support persons with disabilities, only 10% (205) said that persons with disabilities received financial support, and only 12% (258) said that persons with disabilities had access to benefits.

Respondents said that persons with disabilities were living in isolation, with no community supports. A large number of respondents expressed grave concerns about the effects of isolation on the mental health of persons with disabilities.

Table 3 Access to community supports and services

Table 4 Access to financial supports

A representative of an organisation of persons with disabilities in Uganda said:

“Due to isolation and social restrictions it has caused a lot of fear and psychological pain, anxiety, with uncertainty about what will happen next. This may culminate into an increase in mental breakdowns and increase in suicide cases.”

Persons with disabilities around the world reported that they lost their independence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some persons with disabilities said that they were forced to rely on their family members, charities, or NGOs for survival. An Italian respondent with disabilities said “I am afraid that my mum will die of exhaustion and then I will die without her assistance.”

Promising example: collaborative emergency response in Indonesia

Several testimonies described a collaborative emergency response by Indonesian organisations of persons with disabilities. Online meetings were held to discuss the situation of persons with disabilities living in the community led by the Indonesian Mental Health Association. Collective action plans were developed, including the development of videos [20] to raise awareness of the mental health implications of isolation.[21]

4.2 Access to information

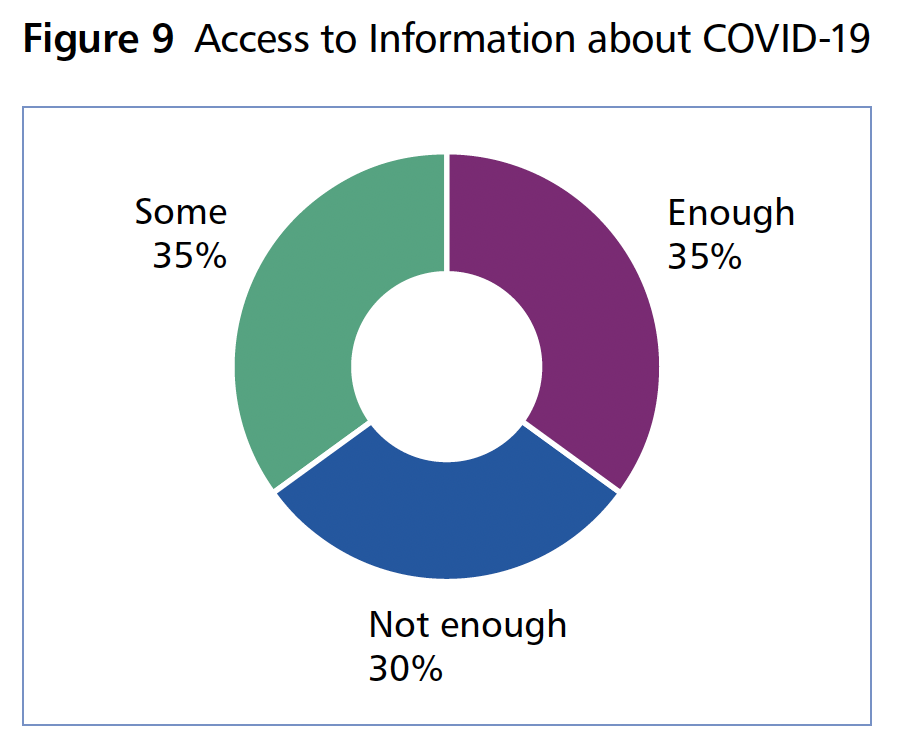

Almost one-third (621, 30%) of respondents said that persons with disabilities did not receive enough information about the prevention of COVID-19 (refer to Figure 9 below for additional responses). The COVID-19 DRM received 345 written testimonies about access to information during the pandemic. There were concerns about access to information in hospital facilities and when persons with disabilities living in the community were isolated without any contacts.

Figure 9 Access to Information about COVID-19

When information about COVID-19 was provided, it was often unclear and confusing. Respondents from Australia, the USA, the UK, and Colombia complained that their government spread misinformation or confusing information about the state of emergency. For instance, an Australian respondent with disabilities complained of “inconsistency & confusion in information on social distancing and use of PPE.” Similarly, a Colombian respondent with disabilities was concerned about the “confusing access to all the information that is provided daily.”

The majority of respondents with disabilities accessed information about the pandemic on television, radio, or social media. However, there were concerns that persons with disabilities living without access to these technologies did not have adequate information about the pandemic. Respondents from Ethiopia, Malawi, Lesotho, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe said that there was no access to information for persons with disabilities living in remote and rural areas.

A representative of an organisation of persons with disabilities in Lesotho said:

“No measures have been taken to inform persons with disabilities about the virus especially in areas where such individuals can’t access information through radio or television.”

When asked if information about COVID-19 was available in accessible formats, 21% of respondents said that information was not available in any accessible formats. Sign language was the most widely-available accessible format (44%), followed by easy-to-read (38%) and audio (33%), as outlined in Table 5 below. Concerns were also raised about the lack of specific types of information, including preventive measures to prevent infection, where to obtain testing and treatment, the nature of emergency regulations and lockdown rules, and accessing emergency food and social assistance schemes.

Table 5 Access to information

Promising example: Sign language videos in Rwanda

In March 2020, the Rwanda National Union of the Deaf (RNUD) in partnership with local government authorities and the Office of the Prime Minister released one of many sign language videos. A Rwandan respondent said that “interpretations during the TV COVID prevention campaigns have enhanced access to information. The Deaf organization increased its efforts by translating all the inaccessible information and sharing them via all social media platforms in a very accessible format (sign language and simplified video).”[22]

4.3 Access to food and essentials

The survey has revealed that persons with disabilities around the globe did not have access to food and adequate nutrition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost one third (633) of the survey respondents in 81 countries said that persons with disabilities in their country could not access food. The ten countries where the highest percentage of respondents reported no access to food were Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, Bangladesh, India, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Peru. Several high-income countries were also among those with high proportions of people who said that they could not access food. More than 25% of respondents from Belgium, Canada, France, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom said that persons with disabilities did not have access to food during the pandemic. The findings indicate that the vast majority of governments did not take the appropriate steps to safeguard and promote the right to access food.

The survey received 131 written testimonies about access to food and adequate nutrition. The written testimonies provide a deep insight into the nature of food distribution across the world. There were reports of increased prices, loss of income, and inadequate financial support during the pandemic. Several respondents from high-income countries complained that they could not afford food and basic necessities as a result of the rising cost of living, including a rise in the cost of medication and rent.

In many countries, persons with disabilities were living in poverty before the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents described how the measures taken by their governments created even worse situations for persons who relied on begging or low-paid jobs to buy food.

A representative of an organisation of persons with disabilities in Nepal said:

“The government announced the stay at home order and lockdown, but could not think of poor daily wage earners who are not getting even a meal a day. People are deprived of food and are in financial crisis and the government has not provided any benefits.”

Many respondents from high-income countries felt that they were abandoned in their homes, with no way of access to food. The COVID-19 DRM survey received written testimonies from persons with disabilities in Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Switzerland, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom who said that they could not access food during the pandemic. Eight respondents from the United Kingdom complained that persons with disabilities were not included on the government’s list of groups that were vulnerable to food shortages. Other barriers identified by respondents included the harsh enforcement of lockdown orders by police and security officials, the removal or severe restriction of necessary personal assistance, and allegations that public food distribution schemes were either inaccessible or unavailable to persons with disabilities, particularly those without relevant documentation.

When food was available, the distribution was initiated by NGOs, organisations of persons with disabilities, or charities, and not by the government. Although some people were receiving food packages, these were planned at the local, rather than the national, level, leading to uneven food distribution throughout the country and food relief efforts not reaching persons with disabilities living in remote and rural areas. Available food packages were often insufficient and did not take special dietary requirements into account. Some people relied on food packages from charities and NGOs.

There was also evidence that people relied on informal supports, such as family, friends, or neighbours to access food.

Promising example: Helpline for older persons in Malta

In Malta the Ministry of Social Policy created a helpline for older and vulnerable people to provide them with support regarding food and medicines that were coordinated and delivered to their homes. There was also a specific email address established for the Deaf community to request food and medicine.

4.4 Police brutality, harassment, and abuse

Around the world persons with disabilities and their family members have had no choice but to break curfew rules to access food and essential medical supplies, because no exceptions were made for them. Public information campaigns were largely inaccessible throughout the pandemic. The majority of respondents (77%, 1105) said that they did not have information about penalties resulting from breaking state of emergency rules (fines, sanctions, arrest) imposed on persons with disabilities. Furthermore, one-third of respondents said that they did not have access to food or medical supplies. This resulted in a dangerous situation in which police and security forces tasked with enforcing lockdowns encounter persons with disabilities leaving their homes to meet their basic needs.

The COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor survey received 370 written testimonies from all continents. The testimonies reveal an alarming global phenomenon of police harassment, torture, and murder of persons with disabilities and their family members. The findings indicate that persons with disabilities were particularly vulnerable to various forms of exploitation, violence, and abuse in countries with strict curfews and strong police or military presence. In the most extreme cases, breaking curfew rules was a matter of life or death. For example, an Army veteran23 with post-traumatic stress disorder was shot and killed in the Philippines. A respondent from a Ugandan organisation of persons with disabilities said “I know two PWDs who have been shot at because they were outside in curfew time. These were deaf people and didn’t know what was happening.”

There were reports of police brutality against women and girls with disabilities who broke the curfew rules to seek food. For instance, a respondent from a Nigerian organisation of persons with disabilities said that “a mother of a child with Cerebral Palsy was harassed by policemen on her way to collect food relief at one of the distribution centres.” Likewise, a Ugandan respondent said that “a woman with a disability was beaten up after curfew time. She was looking for food.” A South African respondent said that “parents have been fined or arrested for going to buy diapers or medication for their child with a disability.”

Respondents from around the world reported that they were living in fear of the police. In Europe, respondents from Italy, the UK, and France said that they were afraid to leave their homes. Many people believed that the police were unreasonable and heavy-handed.

An Italian respondent said that “fines were given to persons with disabilities who sat on benches or went out on the street with their caregivers.” A Russian respondent with disabilities said that they were “caught by police on the street. They took my personal data and warned me that next time I would be charged a fine for the same offense.” Emergency measures enacted by the French government to allow persons with autism to go out more often were criticised by three participants. They condemned the law for giving the French police powers to determine who is autistic. A French respondent explained that there were “fines for persons with autism or parents of children with autism who have permission to go out but the police find ‘not autistic enough’.”

There were also stories of police harassment of family members trying to make contact with their loved ones, many of whom were locked inside institutions, with no means of contacting the outside world. A French respondent said that “a lady was fined for waving (hello) out the window (closed) to her husband who lives in a retirement home.” A Norwegian organisation of persons with disabilities said that “families/legal guardians trying to visit have sometimes been threatened with police action.”

4.5 Recommendations on Community Supports

In accordance with their obligations under international law, particularly the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the COVID-19 DRM calls on governments, funders, and global actors to take the following immediate steps to avoid a further breakdown of community services and supports:

- Guarantee full participation and meaningful involvement of persons with disabilities and their representative organisations at every stage of the response.

- Safeguard community-based services including personal assistance, home supports, and assistive technology.

- Provide information about the state of emergency in multiple, accessible formats.

- Enact emergency measures to ensure adequate and affordable food and medication distribution throughout the country, including rural and remote areas.

- Provide immediate financial assistance to persons with disabilities to cover the additional cost of living and the rise in the cost of food, medications, and other essential supplies.

- Work with private sector companies such as supermarkets to ensure that food is delivered to the homes of persons with disabilities who are unable to leave, and encourage them to allocate dedicated times for vulnerable shoppers, including persons with disabilities.

- Investigate and hold accountable police and other security services which abuse, injure, or kill persons with disabilities.

- Put in place necessary measures to protect persons with disabilities who are in situations of risk, especially during curfews, lockdowns, shielding orders, or shelter at home orders related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Ensure all security briefings and reports take into consideration the perspectives and rights of persons with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Ensure police officers and security forces are trained to take into account the specific needs of persons with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Part 5 Disproportionate impact on underrepresented groups of persons with disabilities

Specific populations of particularly marginalised persons with disabilities have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments around the world have failed to recognise the impact of the pandemic on groups that are multiply marginalised. They have failed to take measures to include and protect the most underrepresented groups of persons with disabilities, including children, women and girls, persons experiencing homelessness, and persons living in remote and rural locations.

The partners on the COVID-19 DRM initiative sought to gain information on the specific situation facing children with disabilities, older persons with disabilities, homeless persons with disabilities, and those living in rural and remote locations. However, responses also captured the experiences of other underrepresented populations including women and girls with disabilities, deaf or hard of hearing persons, persons with intellectual disabilities, persons with psychosocial disabilities, persons with deafblindness, persons with autism, and persons with disabilities from indigenous communities. Inclusive responses must not only respond to the specific issues faced by these populations, but should proceed on an intersectional basis, addressing the enhanced risks faced by persons with disabilities who experience multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination.

5.1 Children with disabilities

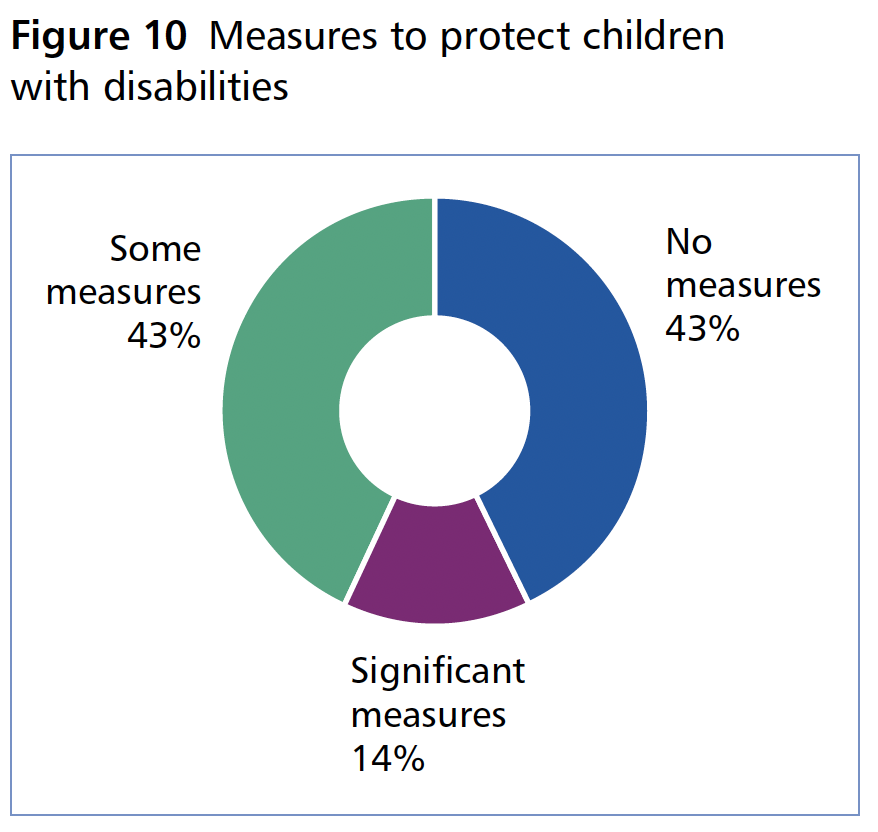

The survey findings suggest that children with disabilities were disproportionately affected by the measures taken by governments during the pandemic and experience multiple forms of discrimination on the basis of disability and age. Forty-three percent (623) of respondents who knew about the situation of children said that their government took no measures to protect the health and safety of children with disabilities in institutions or in the community. The written testimonies reveal that many essential supplies and services were unavailable to children in the community and in institutions. Respondents from around the world reported that children did not have access to food and medicine. Moreover, children with disabilities did not have access to essential healthcare, respite care, rehabilitation, or education.