CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY:

Decades of Violence and Abuse in Mexican Institutions for Children and Adults with Disabilities

Authors:

Laurie Ahern, President, DRI

Lisbet Brizuela, MA, Mexico Director, DRI

Ivonne Millán, JD, Legal Advisor-Mexico, DRI

Priscila Rodríguez, LL.M, Associate Director, DRI

Eric Rosenthal, JD, LL.D (hon), Executive Director, DRI

Research team:

Javier Aceves, M.D

Marisa Brown, RN

John Heffernan

Matthew Mason, PhD

Karen Green McGowan, RN

Diane Jacobstein, PhD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Disability Rights International expresses our gratitude to all the people who contributed to the preparation of this report. DRI recognizes the work and collaboration of the specialists who accompanied us during the research process and their valuable observations and opinions: Dr. Javier Aceves, M.D., a retired professor from the Department of Pediatrics at the University of New Mexico; Dr. Diane Jacobstein, Ph.D., of the Center for Child and Human Development at Georgetown University; Dr. Matthew Mason, DRI’s Senior Mental Health and Science Advisor; Marisa Brown. RN, previously of the Center for Child and Human Development at Georgetown University; Karen Green McGowan, RN, Clinical Nurse Consultant; and John W. Heffernan, activist and chair of DRI’s Board of Directors.

DRI also thanks the National Human Rights Commission, the Baja California Human Rights Commission, and the Yucatán State Human Rights Commission for accompanying us to visit institutions and arranging the visits.

We deeply appreciate the testimonies from people with disabilities living in institutions, services providers, former staff, professionals, and volunteers. Their testimonies were a crucial contribution for this report.

DRI’s work in Mexico is supported by the Ford Foundation, the Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation, the Holthues Trust, and several anonymous funders.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

States Parties to the present Convention recognize the equal right of all persons with disabilities to live in the community, with choices equal to others. – UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), Article 19

They arrive here. They die here. The government provides no alternatives. – Director of Pastoral de Amor, Yucatan

This report documents severe and pervasive human rights violations against children and adults with disabilities in Mexico. Within the country’s orphanages, psychiatric facilities, social care homes, and shelters for people with disabilities, inhumane and degrading treatment is common, and many practices amount to torture.

Violence, sexual abuse, forced sterilization, forced abortion, and trafficking for labor or sex is common.

Children and adults with disabilities throughout Mexico are confined to institutions, segregated from society, and exposed to these dangers – because of the country’s failure to create social supports that would allow people to lead a full life in the community. Mexico’s law strips people with disabilities of the right to make decisions about their own lives – leaving them unable to file complaints or demand accountability when they are abused.

DRI investigators recorded extensive accounts of physical and sexual abuse. At the Casa Esperanza, the Director of the facility explained that women and girls are sterilized to cover up sexual abuse:

I cannot protect women from being raped by workers who come into the facility…. so, we sterilize all of them. – Director of Casa Esperanza

Authorities at six institutions informed DRI that they routinely sterilize women. According to the directors of the public psychiatric hospitals El Batán and Villa Ocaranza, all women of ‘fertile’ age have been ‘taken care of’ – surgically sterilized or given a contraceptive patch. In the private institution El Recobro in Mexico City, staff report women who arrive pregnant are sterilized after they give birth.

The problem of sterilization is not limited to women detained in institutions. DRI conducted a survey of over fifty women seeking outpatient mental health treatment in Mexico City, and a majority reported that they had been sterilized without their knowledge or consent. In the same survey, an even larger majority reported that they had been sexually abused at the hands of health care providers. DRI similarly received extensive reports of sexual abuse within institutions:

At least eight women told me they were victims of sexual abuse by male staff. – volunteer in CAIS Cascada

It makes us feel disgusted. – woman at CAIS Cascada, a facility where women are forced to have sex and compensated with cigarettes or money.

In the absence of meaningful treatment in institutions, people with disabilities are often controlled through the use of physical and chemical restraints.

I handcuff them and we tie their feet and leave them face down for hours. – Director of the Centro de Rehabilitación Fortalécete en Cristo, Baja California

Throughout the DRI investigation, I encountered a lack of awareness of professional standards and commonly accepted practices, such as positive behavioral supports. Such practices could be used to prevent and respond to challenging behavior and to make restraint unnecessary. Restraint is traumatizing, inhumane and counterproductive. – Dr. Diane Jacobstein, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development

At one facility, Casa Hogar de Nuestra Señora de la Consolación de los Niños Incurables in Mexico City, run by a Catholic order, investigators observed dozens of children and adults held in cages and tied down to beds. At the Asociación Hogar Infantil San Luis Gonzaga in the State of Mexico, nearly all children and adults were restrained with layers of bandages from head to toe for at least an hour a day. We observed young people with disabilities whose hands were tied to bars above their heads as they were forced to walk on treadmills for extended periods of time, purportedly as a form of “physical therapy.” International law prohibits the use of restraints as “treatment,” as this practice can be dangerous and traumatizing. When one minor finished his time on the treadmill at this facility, he lay face down on the mat in pain, requiring a heating pad for his shoulders.

Unproven and dangerous treatments, such as the use of psychosurgery for aggressive behavior among people with intellectual disabilities or autism, have been reported in a Spanish medical journal. The article described how adults may consent to allow psychosurgery on their children if they exhibit aggressive behavior – whether or not other treatment has been tried. Yucatan’s mental health law specifically allows psychosurgery on children. The Mexican Institute for Social Security reported the use of lobotomies on women with anorexia. Electro- convulsive therapy (ECT) is used without anesthesia or muscle relaxants – a dangerous practice that causes severe pain. The use of ECT without anesthesia has been condemned by the World Health Organization and described as torture by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture. One recipient said he received 11 sessions as punishment, after a dispute with the Director of the Tabasco Psychiatric facility. The Deputy Director ordered a suspension of the procedure after the man’s condition deteriorated so much that the Director “thought he would die.”

In several facilities, dangerous conditions and inappropriate care has led to high death rates. At the El Batán psychiatric facility, for example, authorities report that at least 98 of the approximately 300 people at the facility have died in the last two years. The Director of the facility said that that the high death rate was due to the “misuse of psychotropic medications” – an admission of gross medical neglect at the facility. This death rate of 27% from preventable causes is at least ten times the risk of sudden premature death in similar institutions of other countries.1

In the Psychiatric Institution Villa Ocaranza in Hidalgo, the director told DRI that the most common cause of death among persons with disabilities was “food aspiration” (choking) but, despite this, the institution had not hired a specialist to assist with feeding and choking prevention practices or come up with an individualized diet to reduce the risk of aspiration.

They are here for social reasons. They have been abandoned by families and they have nowhere to go. – Ministry of Health Official, Yucatan

They stay here until they die. – Director, Casa Hogar San Pablo, Querétaro

Throughout Mexico’s social service system, the primary reason given for confinement in an institution – according to both staff and person with disabilities interviewed by DRI – is the lack of community-based and family-based supports. Authorities at psychiatric facilities, social care homes, and homeless shelters agree that the vast majority of detainees are not dangerous and have no medical or psychiatric reason to be there, but they simply cannot obtain the support or treatment they need while living at home or with their family. Similarly, the vast majority of children in Mexico’s orphanages have living relatives, and they are placed in these facilities because of poverty or lack of supports to allow them to live with their family.

Children and adults with disabilities confined to institutions are usually condemned to a lifetime of segregation from society. The dangerous conditions at the facilities and lack of care and treatment often results in a decline in mental health. Children in orphanages often cannot attend mainstream schools, and adults lose out on employment opportunities, making it more and more difficult over time to reintegrate into society.

This report documents a culture of impunity in which abusers are not held accountable and government authorities fail to respond to known human rights violations in institutions. DRI has documented and exposed abuse and improper segregation in closed institutions in detailed reports in 2000, 2010, 2015 and 2019. In 2014, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities condemned Mexico for its failure to enforce CRPD Article 19’s obligation to avoid segregation by creating community-based services and support for people with disabilities. The Committee called on Mexico to adopt laws to stop labor exploitation of people with disabilities and forced sterilization. In the decade since the UN issued these recommendations, Mexico has failed to change its discriminatory laws and flouted UN recommendations to end segregation by providing community alternatives to institutions. At both national and state levels, the government has knowingly and intentionally allowed abusive and dangerous practices to continue by failing to change policies and continuing to direct the vast amount of funding for services into abusive institutions rather than community care.

Plans to remodel and create new facilities show the government’s intention to preserve the current institutional model instead of transitioning to a new, community model. – DRI Expert Dr. Javier Aceves, after interviewing authorities from the System for Family (DIF)

Despite well documented abuses, Mexico has not created the human rights oversight and enforcement systems necessary to protect its institutional populations. Indeed, creating policies and programs to respond to abuses has been impossible because the main authorities responsible for operating these services – the national Ministry of Health, the System for Integral Family Development (DIF), the Ministry for Social Development, and the National System for the Integral Protection of Children and Adolescent (SIPINNA) – do not even track the number of people placed within these systems.

Overview of findings: adult institutions

DRI visited 35 institutions where adults with disabilities are detained – sometimes mixed with other populations such as children, drug addicts and migrants. In 85% of the institutions DRI investigated for people with disabilities, we observed or authorities reported the use of seclusion, physical restraint, or chemical restraint. In some facilities, DRI observed all three of these abusive practices.

There were only five facilities where DRI investigators observed no inhumane and degrading treatment in progress. Of these, two of them were expensive private facilities, out of reach for most Mexicans. In the other three, there was a nearly complete lack of treatment and little active care and the people detained there were left to fend for themselves.

DRI observed the use of physical and/or chemical restraints in 83% of the institutions for people with disabilities we visited – much of it for prolonged periods of time. In Mexico, there are no laws limiting the use of restraint and no requirement to document each use, so it is impossible to know how long these practices continue.

DRI observed the use of seclusion rooms in a third of the institutions we visited. At the Instituto de Psiquiatría in Mexicali, Baja California, for example, DRI found a man with an intellectual disability who had been held in a seclusion room for more than 4 months. At the same facility, DRI found a pregnant woman in a seclusion room. She told DRI, “I am afraid to stay here.”

Most institutions visited by DRI detained adults with disabilities against their will or without their informed consent. In most such facilities, people with disabilities are detained indefinitely, often until they die. Two exceptions were psychiatric hospitals (Fray Bernardino in Mexico City and Instituto de Salud Mental in Tijuana, Baja California) that do not permit long term institutionalization and only accept patients whose families sign documents declaring that they will return and pick them up.2

New patients are often targeted by other patients and are raped. Staff knows about this and they do nothing to stop it. – staff at CAIS Cuemanco, a public homeless shelter for men with disabilities in Mexico City

In at least a third of the facilities (11 institutions) DRI found forced labor or trafficking – adults with disabilities forced to work without compensation. Most of the forced laborers are women used as cleaning staff at the facility, but in some cases, the same women are forced to work at the homes of staff and are made to have sex with staff.

I have to wash the dishes and do whatever the staff tells me to do, I do not like being here, and sometimes I cut myself. – woman at Casa Esperanza

At Casa Esperanza, women were routinely raped by staff and outside workmen coming into the facility. Effectively, rape was being used as part of the remuneration for men working at the facility. The same women were also forced to clean the homes of their abusers. Despite DRI’s exposure of these abuses, there were no criminal convictions as a result of our investigation. All but one of the survivors were again detained in locked facilities, and at least one of them reported she was sexually abused again in the new facility. Authorities have refused to allow DRI to visit the survivors and have tried to prevent DRI’s Mexico staff from access to information about their cases.

At Casa Hogar la Divina Providencia in the State of Mexico, DRI found that 32 of the 152 persons with disabilities serve as staff without salary. At another facility, Centro el Recobro, there are only three staff to provide ‘care’ to almost 200 women. More ‘functional’ women detainees are paired with women who are in need of more support and are given the job of providing that care, without remuneration. Men and women at various facilities reported to DRI that they had no choice in doing work for the facility. Even if some formality of consent were sought, however, the total power of authorities over detainees is such that this labor should not be considered voluntary.

In 83% of institutions for people with disabilities in Mexico, DRI found inadequate, inhumane, and degrading conditions including unhygienic facilities, lack of privacy, beds and mattresses in poor shape, and poor nutrition, among others. The CAIS Villa Mujeres, a homeless shelter in Mexico City, houses approximately 400 women with disabilities in conditions of extreme neglect. In 2016, DRI found feces and urine on the floor and on the clothing of women – with an overpowering stench throughout the facility. Staff stated that cleaning supplies were regularly stolen and acknowledged that the facility is dangerously unhygienic. DRI visited the facility in 2016 and 2018 and found conditions unchanged.

There are bedbugs and no water to clean. Everything is filthy. – Woman living at CAIS Villa Mujeres

Few institutions provide habilitation or rehabilitation to preserve and support independent living skills or assist people with disabilities reintegrate into the community. There is a widespread lack of care that is based on individualized assessments and delivered by qualified, trained staff.

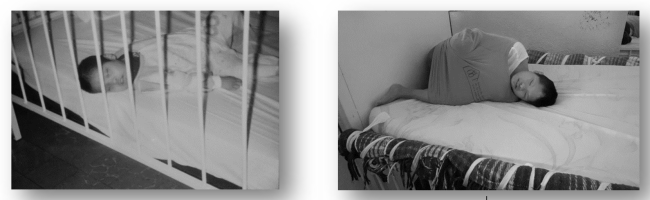

Overview of findings: children’s institutions

Children are especially vulnerable to the dangers of institutional placement. Extensive scientific research has shown that the placement of any child in an institution is likely to cause irreversible psychological damage and cognitive delays. Children need to form emotional attachments at an early age, or they may permanently lose the ability to do so. For this reason, the CRPD creates especially strong protections for children.3 In General Comment No. 5, the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) unequivocally states that “[f]or children, the core of the right to be included in the community entails a right to grow up in a family.”4 The CRPD Committee goes on to explain that:

Large or small group homes are especially dangerous for children, for whom there is no substitute for the need to grow up with a family. ‘Family-like’ institutions are still institutions and are no substitute for care by a family.5

In Mexico, there is a broad lack of supports for families of children with disabilities, forcing parents to give up their children and place them in institutions. In almost all of the institutions DRI visited, children with disabilities are detained indefinitely and remain segregated from society after they have turned 18 and become legal adults. None of the institutions had individualized plans to reintegrate the children to a family setting. In 65% of institutions DRI visited, children were not receiving any type of formal habilitation or rehabilitation programming and were not attending a mainstream school.

DRI visited twenty-one institutions where children with disabilities are detained. In 86% of these institutions DRI found the use of physical restraints, chemical restraints, and seclusion. In 25% of the institutions visited, DRI found that all three of these restrictive and abusive practices were used on children.

In the institution Hogares de la Caridad in the state of Jalisco, for example, DRI found a 17-year-old boy with autism wrapped in a sheet, confined with duct tape and held in a cage. According to staff, restraints are needed because of the boy’s behavioral problems. At this facility and many other documented in this report, physical restraints are used instead of mental health or rehabilitation programs that might address the underlying cause of difficult behavior. Throughout Mexico, DRI investigators found staff at institutions were unaware of mental health and behavioral programs for people with disabilities– resulting in widespread use of physical restraints.

Within Mexican institutions, children with disabilities in institutions are commonly placed in danger due to a range of inappropriate treatment practices and lack of oversight. For example, DRI observed dangerous treatment practices and a high death rate at the private institution Casa Gabriel, near Ensenada, in the state of Baja California. Most of the children there had cerebral palsy and some rarely had the opportunity to get out of bed. These children appeared to have muscle atrophy from a lack of movement and exercise. Many of the children were fed with feeding tubes, seemingly for the convenience of staff, as there was no documentation of medical necessity. According to the coordinator of Casa Gabriel, in 2017 there were 32 children living there. When DRI visited the institution in February 2019, only 19 of those children remained. Four children – between 12 and 22 years old– died within days of each other in February 2018.

We interviewed Gloria, a single woman who had five children. After her husband left her, she had to leave the home for 12 hours at a time to earn the money to feed her children. She left her children in the care of the eldest. When child protection authorities discovered this situation, they took all the children away from her. Instead of providing support to allow Gloria to keep the children she loved, the children were placed in an orphanage. They ended up in the very abusive Ciudad de los Niños. – DRI investigator

DRI received allegations of sexual and physical abuse in at least one quarter of the institutions visited. In the case of Ciudad de los Niños in Salamanca, Guanajuato, a judge found that the children detained at the institution had been victims of grave human rights violations, including physical, psychological, emotional, and sexual abuse. Girls as young as 11 were raped at the facility. The judge found that many children were born in the facility to other girls, who had likely been trafficked for sex. At least 137 children were registered in the name of the priest who runs the facility, likely to allow for illegal adoptions abroad. Despite these allegations, the priest has been allowed to continue to operate at least six other institutions in Guanajuato and Michoacán.

The case of La Gran Familia, a 500-bed private institution in Michoacán, has received extensive press attention. The facility is commonly known as Mama Rosa after its founder, Rosa Verduzco.

Children at the facility were subject to physical and sexual abuse, placement in isolation rooms, deprivation of food, and filthy living conditions with rats and bedbugs. While the facility was closed in 2014, many its survivors with disabilities were never compensated for the abuses they experienced. For children with disabilities, liberation from Mama Rosa resulted in placement in other institutions because of a lack of supported for families, kinship care, and foster care for children with disabilities throughout the country.

DRI investigators interviewed a survivor, who was 18 years old when he was saved from Mama Rosa. He was never given any compensation. He has experienced depression and anxiety as a result of the trauma he experienced at the facility. Instead of being offered any form of care for this trauma in his home or at a community setting, the survivor has since been re- institutionalized as an adult.

Imagine the fear, the anxiety. I leave the institution in August 2014 and from November to December I was locked in the psychiatric hospital, confined there. My future was uncertain. I didn’t know if I was going to leave or where I would go. – survivor, Mama Rosa survivor

There are very few examples of new community support programs throughout Mexico. The experience of the survivor is similar to the dozens of survivors of the Casa Esperanza facility exposed by DRI. In the absence of any form of community care, 36 of the 37 survivors were placed in new institutions. Two Casa Esperanza survivors died within a year of their placement in new institutions.

For children with disabilities separated from their families, options are similarly limited. For many years, government authorities in Mexico City have promised that they are creating pilot programs to help children with disabilities receive the supports they would need to be placed in foster families. But to date, DRI has not been able to identify any such programs in the areas we have investigated.

Supported foster care programs that would allow children with significant support needs to leave institutions and grow up with a family are practically unknown anywhere in Mexico. – Juan Martin Perez, Executive Director from the Child Rights Network in Mexico (REDIM)

Many of Mexico’s institutions for children are supported by foreign donors, corporations, and volunteers. The United States Department of State has warned in its Trafficking in Persons Report about the dangers of engaging volunteers in orphanages:

Volunteering in these facilities for short periods of time without appropriate training can cause further emotional stress and even a sense of abandonment for already vulnerable children with attachment issues affected by temporary and irregular experiences of safe relationships.6

Despite these dangers, volunteers play an important role in perpetuating Mexico’s orphanage system. At Pan de Vida in Queretaro, for example, individual volunteers pay hundreds of dollars to stay at the facility for up to 14 days. And the lack of oversight and control exposes children to dangers of abuse.

CONCLUSION: CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY

This report documents an overwhelming pattern of severe and pervasive human rights violations directed at people with disabilities. The primary reason for institutionalization in Mexico is the State’s failure to provide community-based services and supports necessary for people with disabilities to live in the community. Effectively, institutions are the only option for children and adults with disabilities in need of support. People with disabilities without families willing or able to support them are relegated to languish in institutions without hope of returning to the community. Children with disabilities may have loving families but without support, thousands of parents of children with disabilities have no choice but to give up their children. Many families are forced by child protection services to place their children in institutions.

Placement in institutions contributes to increased disability, health risks and trauma. Segregated from society, children and adults with disabilities are exposed to the near certainty of violence, torture, and heightened risk of early death.

The government of Mexico must be held internationally accountable. Almost certainly, no country in the world has been better informed about the implications of its laws and policies toward people with disabilities than Mexico. Over the last 20 years, DRI has conducted extensive documentation and brought international attention to this pattern of abuse by publishing four reports prior to the present report: “Mental Health and Human Rights in Mexico” (2000); “Abandoned and Disappeared” (2010); “No Justice” (2015); “At the Mexico-US border and segregated from society” (2019). In investigating these reports, DRI has visited over sixty institutions in more than a dozen states across Mexico where thousands of children and adults with disabilities are detained in dangerous conditions and subjected to atrocious abuses that amount to torture.

Both the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee)7 and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights8 have issued findings that support those of DRI – putting Mexico on notice that its treatment of people with disabilities violates a broad range of fundamental rights under the CRPD and the American Convention.

The fact that so little has changed in Mexico demonstrates not just a culture of impunity for human rights violators, but something more: the intentional and knowing perpetuation of practices with such severity and on such a scale that amounts to crimes against humanity.

Crimes against humanity are legally defined under the Rome Statute. A “crime against humanity” takes place when one of the acts recognized under the Statute is widespread and systemic and “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”9 DRI has conducted an in-depth legal analysis, posted at www.DRIadvocacy.org, demonstrating that the practices in this report meet the strict legal definition of crimes against humanity.

The abuses documented in Mexico are grave – The system of institutionalization in Mexico profoundly affects every aspect of the lives of tens of thousands of children and adults with disabilities detained in institutions. People with disabilities in institutions are stripped of their rights, unable to exercise them as they are indefinitely locked away and abused. They are under the de facto guardianship of the institution’s director and unable to challenge their detention and access legal recourse to stop the abuse they are subjected to. Several studies show how institutionalization in itself is traumatizing for persons with disabilities and particularly for children, leading to intense suffering and trauma.10 The suffering, abuse, and helplessness they are abandoned to amounts to “substantial harm” and leads to “further segregation, isolation and impoverishment.” Particularly in the case of children with disabilities, the system of institutionalization “perpetuates children’s marginalization and vulnerability by negatively affecting their lives, security, best interests, family life, integrity, education, human development, well-being.”11

Human rights violations are systemic – These violations are a product of segregating people with disabilities in institutions throughout Mexico. The Mexican government continues to invest in institutions and, by doing so, to perpetuate institutionalization. The Ministry of Health allocates approximately 1.6% of its budget to mental health; 80% of this goes to the operation of psychiatric hospitals.12 Psychiatric institutions across the country continue to receive federal and state funding.13 The near-exclusive reliance on in-patient care – as reflected in part by where the government invests public resources – demonstrates that the government relies on a segregated, institutional model of care.

Mexico has maintained this system and failed to change laws despite twenty years of DRI’s effective public exposure and the very strong findings and recommendations of the CRPD Committee14 (see next section). The segregated, abusive, and dangerous system of institutionalization in Mexico is not an isolated or random event; rather, it’s the result of legislative and policy violations and omissions on the part of the State to fully guarantee the right of tens of thousands of children and adults with disabilities to live in the community, in accordance with Article 19 of the CRPD and thus, it is a systemic issue.

Mexico’s actions are intentional and causing great suffering – One of the ‘acts’ enumerated by the Rome Statute are “inhumane acts […] intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.”15 Under the definition of the Rome Statute, the intent requirement for liability is “knowledge of the attack.”16 In the case of institutionalization in Mexico, Mexico has been repeatedly on notice regarding the grave violations committed in institutions and how its system of institutionalization is contrary to international law and causing great harm and suffering to thousands of people with disabilities.17 Despite this, Mexico has not only not taken any meaningful action to end this system, it has continued to institutionalize people with disabilities and to allocate resources to the very institutions where their rights are being egregiously violated. By fostering a system of institutionalization with the knowledge that it is in violation of international standards and of the great suffering of the people with disabilities subjected to it, Mexico is demonstrating the level of intentionality required by the Rome Statute.

It is not enough for Mexico to argue that it is institutionalizing persons with disabilities for “therapeutic” or “protection” purposes. Former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak has made clear that the stated intent of a health care professional to provide ‘treatment’ is no defense of a practice that meets the other elements of torture. “This is particularly relevant in the context of medical treatment of persons with disabilities,” says Nowak, “where serious violations and discrimination against persons with disabilities may be masked as good intentions on the part of health professionals.”18

When there is a long-standing pattern of practices and a failure to correct them, the former UN Special Rapporteur Against Torture Juan E. Mendez says that it is reasonable to infer that authorities engaging in such practices intend the natural harmful consequences of their actions and are motivated by discriminatory animus, rather than by a legitimate therapeutic purpose.

The Rome Statute establishes that an “‘attack directed against any civilian population’19 means a course of conduct involving the multiple commission of acts referred to in paragraph 1 against any civilian population, pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy to commit such attack.” As established by international war tribunals, an attack does not need to happen in the context of war or conflict; instead, “an “attack” is an “unlawful act of the kind enumerated in Article 7(a) to (i) of the Statute . […] An attack may also be non-violent in nature, like imposing a system of apartheid […] or exerting pressure on the population to act in a particular manner.”20 Thus, no physical violence is necessary for an attack, “but merely multiple instances of any conduct on the list, pursuant to a state policy.”21

Human rights protections must be strengthened. Existing international law on crimes against humanity does contain some limitations that should be addressed by the international community. No one individual is responsible for the laws and policies that have left people with disabilities in dangerous conditions for decades. A legal framework must be established to allow for State authorities to be held collectively responsible for such crimes on a large scale. The international body with greatest experience in disability rights, the CRPD Committee, should be given legal authorization to take action to investigate these crimes and determine how criminal responsibility should be assigned. DRI calls on the UN Special Rapporteur on Disability, as well as the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, to study and recommend steps to improve international law to respond to the kind of knowing, intentional, severe, and widespread abuses documented in this report.

It has been twenty years since DRI first brought the abuses in Mexican institutions to world attention22 – and more than ten years since the CRPD entered into force. Mexico was a leader in calling for the United Nations to draft the CRPD, yet it has not applied the most fundamental protections of this convention to its own citizens with disabilities who are confined to institutions. A higher degree of accountability is needed than Mexico has already received from the CRPD Committee and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The lives of thousands of children and adults with disabilities depend on it.

Samuel Ramirez facility, State of Mexico, 2019

Hogares de la Caridad, Jalisco, 2018

“El Batán,” Puebla, 2019

Casa Hogar San Pablo, Querétaro, 2018

CAIS Villa Mujeres, Mexico City, 2016

Casa Esperanza, Mexico City, 2015

METHODOLOGY

This report is the result of a five-year investigation on the conditions and abuses that adults with disabilities and children with and without disabilities face in institutions in Mexico, conducted by Disability Rights International (DRI) from 2015 to 2020. The main objective of this report is to document progress on the recommendations made to Mexico by the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in its Final Observations on the Initial Report in 2014.

For the preparation of this report, DRI carried out investigations and monitoring visits to 55 public and private institutions in 11 states across Mexico: Baja California, Mexico City, State of Mexico, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Morelos, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro and Yucatán. In the investigations carried out in the states of Baja California and Yucatán, DRI collaborated with the Baja California State Human Rights Commission (CDHBC by its acronym in Spanish) and the Yucatán State Human Rights Commission (CODHEY by its acronym in Spanish), respectively.

Over 4,000 children and adults are detained in the institutions visited by DRI in the course of this investigation. The institutions visited include public and private orphanages, residential schools for children, psychiatric facilities, social care homes, residential drug treatment centers, and shelters where people with disabilities are placed or detained. For more detailed information on the types of institutions visited see Annexes III-IX. Thirty-five of the institutions visited detain adults with disabilities. Over half of the institutions visited (twenty-three) also include adolescents or children. The other twenty-one institutions visited by DRI detain children with disabilities. In some of the institutions visited, DRI also found adults with drug and substance abuse problems, migrants, indigenous children, and population with HIV. Sometimes adult populations were mixed together with children with and without disabilities.

It is impossible to estimate the total number of children and adults segregated from society in institutions in Mexico because no official estimates are available. Indeed, given the myriad of government authorities responsible for different institutions, no single government authority is responsible for compiling information of this kind. In some cases, DRI has observed private institutions where people are detained without any government regulation or oversight.

All institutions where children are confined receive children sent by the state children’s authority (DIF), which means that the government is responsible and often complicit in their detention and abuse. While children’s institutions are commonly referred to as “orphanages,” a great majority of children placed in these facilities have at least one living parent or close family member in the community.

This report is based on interviews with staff and people with disabilities detained at institutions. DRI also interviewed authorities from the Ministry of Health, the National DIF and state-level DIF authorities, and the Ministry of Social Welfare, among others. This report also includes responses to ‘requests for access to information’ filed by DRI.

The DRI team that conducted the investigations consisted of disability rights lawyers, special education specialists, and international experts in mental health, disability, childhood and trauma. The international experts that accompanied DRI in one or several of investigations were: Dr. Matt Mason, Ph.D.; Diane Jacobstein, Ph.D, and Marisa Brown, RN, all three formerly from the Center for Children and Human Development at Georgetown University; Dr. Javier Aceves, MD, a pediatrician, and John Heffernan, human rights defender and chairman of the DRI Board of Directors.

To protect the identity and privacy of the people interviewed, DRI uses pseudonyms throughout this report.

EMBLEMATIC CASES

The following cases documented in detail by DRI provide an example of the violence and abuse against children with and without disabilities that we observed in institutions throughout Mexico. These cases, which DRI has exposed to government and public attention, show that Mexico has long known about the dangers and abuses in residential institutions but it has failed to take the necessary actions to change the model of care or address the underlying cause of abuse: segregation from society and lack of accountability. In every case documented here, Mexico has also failed to take effective actions to protect victims of abuse and provide reparations.

Casa Esperanza, Mexico City

DRI’s Casa Esperanza para Deficientes Mentales (hereinafter “Casa Esperanza”) case, now pending before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), demonstrates the extent of abuse faced by people with disabilities in institutions. DRI first visited Casa Esperanza, a 37-bed private facility in Mexico City, because it was one of dozens of institutions on a “blacklist” prepared by Mexico’s authority for children and families (DIF) of known, abusive facilities.23 DIF’s “blacklist” did not stop States throughout Mexico from sending children to this facility at the government’s expense. When DRI first visited Casa Esperanza, we observed children and adults at the facility locked in cages and with their arms tied with duct tape behind their back, left permanently in contorted positions.

During this visit, the director admitted to DRI in an on-camera interview that all women admitted to the facility were sterilized because the facility could not protect them from being sexually abused by staff and outside workers. DRI and the Mexico City Human Rights Commission (CDHCM by its acronym in Spanish) conducted follow-up investigations which confirmed that women and girls were in fact being sexually abused and raped and that sterilization was used to cover up the abuse. Further investigations by CDHCM uncovered that at least seven women with disabilities had scars consistent with a permanent surgical sterilization method (bilateral tubal ligation) which was performed without their consent.24 The sterilization was ordered or carried out by DIF, the children’s protection authority. For those women who were not surgically sterilized, other contraception methods were used to prevent pregnancies. In the case of one young woman, a medical checkup revealed that an intra- uterine device had been inserted in her uterus.25

Forced sterilization of women with disabilities is banned by the Mexican Federal Criminal Code, and the criminal codes of 18 states. Despite this, federal regulations not only permit but encourage sterilization of women with disabilities. The National Standard Regulation NOM- 005-SSA2-1993 on "Family planning services" (NOM 005) establishes that “mental retardation” in women is an “indication” for sterilization by “Bilateral Tubal Occlusion,” encouraging the sterilization of this group.

DRI first alerted Mexican authorities to the abuses, torture, and forced sterilization taking place at Casa Esperanza in 2014 and again in 2015. After DRI presented documentary evidence of these abuses to the local authorities, they failed to respond for more than a year.26 During that time, DRI reported on Casa Esperanza to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee), which specifically referenced the facility in its report on Mexico’s compliance with the CRPD. For more than six months after the United Nations issued this report, Mexico failed to stop abuses at Casa Esperanza.27 Finally, in May 2015, DRI gained the assistance of the Mexico City Human Rights Commission to visit the facility with local human rights authorities. DRI obtained testimonies from all the women who were able to verbally express themselves, revealing that they had been systematically sexually abused by staff and outside workers, and that they were forced to work in the institution and in the homes of the institution’s staff.28

DRI suggested to the Mexico City authorities that the residents of Casa Esperanza should remain in the institution (once the abusers had been removed) until community placements could be found for them. DRI filed a petition for precautionary measures with the Mexico City Human Rights Commission to ensure that detainees at Casa Esperanza would not be moved to other, similarly abusive institutions. DRI raised concerns that transferring the survivors to other institutions would put them at risk of suffering new abuses and that they would face a lack of access to adequate care that is inevitable in Mexico’s current institutionalization system.

Mexico authorities ignored this petition and moved the Casa Esperanza residents to other abusive institutions throughout Mexico. In a city of 8.5 million people, the local authorities reported that “no community placements were available.” Within six months, two of the 37 people formerly detained at Casa Esperanza had died. DRI learned that one woman was repeatedly raped inside the institution to which she had been transferred after her release from Casa Esperanza – the testimony of the sexual abuse and rape she endured in the new institution was even more horrific than her abuse at Casa Esperanza.

The Casa Esperanza case demonstrates the total lack of safe and appropriate community placements for children and adults with disabilities in Mexico. Even with extensive international pressure and attention brought by DRI, the United Nations and regional human rights bodies, international and national press, and local human rights commissions, Mexico has been unable and unwilling to create community placements for people with disabilities detained in abusive institutions. People subject to torture, forced labor, and trafficking for sex at this facility have received no reparations for the abuse they suffered and the underlying practices that allowed these abuses to continue.

Instead of providing care in the community, the authorities simply dumped the Casa Esperanza victims into other locked facilities. DRI helped set up an emergency shelter for trauma survivors, but the Mexican government threatened DRI and the non-profit that would run the shelter with prosecution – saying they would hold us liable if the survivors “escaped.” According to the laws of Mexico, these individuals should have been able to leave if they wanted to, and not be detained against their will. In practice, this threat demonstrates how supposedly “open door” facilities are effectively turned into closed institutions. These threats from the government also reveal how disincentives are created for any non-profit or individual that wants to create alternatives in the community that respect the consent of the people they are serving. The government removed the victims from the shelter and put them in institutions, where they have continued to face abuse, torture, and even death.

This case also demonstrates the impunity that permeates grave and well-documented violations against persons with disabilities in institutions. As of today, no state authority has been prosecuted for the rape and torture committed against persons with disabilities at the institution. In fact, the State’s position has been to remove DRI’s access to the victims and their case files. DRI has been unable to monitor the situation of the survivors because the State has refused to let us know where they are and give us access to them. DRI also engaged in a legal battle with the Mexico City Human Rights Commission in order to regain access to the case files. DRI filed a complaint to the National Transparency Institute which, in January 2020, ruled that the violations committed in the Casa Esperanza case are grave and as such, must be made available to the public and to DRI.

Ciudad de los Niños, Salamanca, Guanajuato

In 2017, DRI began monitoring the case of the Ciudad de los Niños in Salamanca, Guanajuato, a private institution which held 130 children with and without disabilities and adults with disabilities. The organization was founded and run for over 40 years29 by Pedro Gutiérrez Farías (Padre Gutiérrez), a Catholic priest. On June 9, 2017, the Ninth District Judge in the State of Guanajuato, Karla María Macías Lovera, issued an amparo judgment in which she found that the children in Ciudad de los Niños had been victims of grave violations, including neglect, inhumane conditions, and physical, psychological, emotional, and sexual abuse and rape – in some cases of girls as young as 11 years old.30 There were also allegations of pregnancies inside the facility, of babies who were born and disappeared or were placed for adoption, and of children who were sent abroad as passports were issued for them. According to the judgment, at least 134 children in the facility were registered with Padre Gutiérrez’s last name.31 Padre

Gutiérrez also runs at least six other institutions in the states of Guanajuato and Michoacán where children are still held.32

According to the findings of the Amparo judgment, for years the state authorities of Guanajuato failed to investigate allegations of abuse in the institution. The Guanajuato DIF was informed about these abuses and did not act to protect the children. On July 13, 2017, DIF took control of the institution – only after the media got access to the Amparo ruling issued by the judge a month earlier and pointed to the inaction of the authorities in the case. For approximately one year, the children remained in Ciudad de los Niños under DIF’s custody.

Instead of creating alternatives to institutionalization and working to safely reintegrate the children with their families or foster families, the state of Guanajuato invested MXN 57,000,000 (around 3 million USD) in the construction of a new institution to which a large number of children from Ciudad de los Niños were transferred. Children and adults with disabilities who had been detained at Ciudad de los Niños were transferred to a different institution.

Padre Gutiérrez appealed the Amparo judgment. The Appeals Court sided with him and overturned the judgment on technical grounds – never challenging the factual findings of the original Amparo, which acknowledged the abuse at the facility.33 The decision of the Appeals Court leaves the victims unprotected. Control of Ciudad de los Niños was returned to Padre Gutiérrez in 2019, and he publicly stated his intention to reopen this institution. In this case, as in the case of Casa Esperanza, DRI has been denied access to the files and victims, so we do not know their current situation.

In May 2020, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH by its acronym in Spanish) issued its recommendation 32VG/2020, which exposed the systematic abuse suffered by children with and without disabilities and adults with disabilities within the Ciudad de los Niños. The CNDH found serious human rights violations such as acts of torture, sexual violence, and cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment committed against children with and without disabilities and adults with disabilities. It also pointed out that the responsible authorities violated the victims’ rights to identity, health, education, free development of personality, dignified care, and child’s best interests. The CNDH exposed the failure by different state authorities to supervise the conditions in which Ciudad de los Niños operated, the existence of a complicit network to protect Padre Gutiérrez, and the obstruction of justice by state and federal authorities.

Despite all the existing evidence, the CNDH did not issue in its recommendations the need to investigate Pedro Gutiérrez Farias as responsible for all the abuses committed in the institution under his charge. The case of Ciudad de los Niños highlights the culture of impunity in Mexico which allows abuses of children and adults with disabilities to continue despite public scrutiny and judicial rulings.

La Gran Familia, Michoacán

La Gran Familia was a private institution in Michoacán that housed around 500 children and adults with and without disabilities. This institution was founded in 1954 by Rosa Verduzco, known as “Mama Rosa.” It is estimated that, in its 60 years of operation, the institution housed around 4,000 people.34 According to the testimony of the survivor, who was detained in La Gran Familia for six years children in the institution experienced extensive neglect and abuse. Conditions in the institution were unhygienic – there was no hot running water, and the food they were served was rotten. Children slept on the floor, and problems with rats and bedbugs were common. Use of isolation rooms was a common punishment. The children were physically and sexually abused, there was trafficking and girls who became pregnant were forced to have abortions. 35

After years of complaints of abuse, on July 15, 2014, the General Attorney’s Office (PGR by its acronym in Spanish) “with support from various authorities, including elements of SEDENA, PF, and the State Police,”36 released the children who were detained there. Some children were able to be reintegrated with their families, but others were sent to different institutions.37

In 2019, DRI met with a survivor, who had lived in La Gran Familia from the ages of 12 to 18. This survivor disclosed that at the institution, he was repeatedly raped by four different perpetrators. He was also held in an isolation period for a period of at least two months. When la Gran Familia was closed, the survivor was 18 years old and did not receive any support to reintegrate into the community because he was legally considered an adult. Since the closure of the institution, he has suffered constant depression and anxiety attacks because of the trauma he endured at la Gran Familia. He has not received any support from the government to assist in his reintegration to the community, education, or employment. On the contrary, he was forced into an institution in order to receive the care and support he needed. Within months of the closure of la Gran Familia, the survivor was admitted to the Fray Bernardino Álvarez Psychiatric Hospital where he was physically restrained. He told DRI investigators: “imagine the fear, the anxiety. I leave the institution in August 2014 and from November to December I was locked in the psychiatric hospital, confined there. My future was uncertain, I didn't know if I was going to be able to leave and where would I go.”

The survivor told DRI that more than ten of his friends from La Gran Familia have died by suicide “because they have not been able to deal with the aftermath.” He adds that he has also tried to kill himself: “I locked myself in my room, got three grams of coke and tons of alcohol and I hung myself. I was already beginning to have suicidal episodes.”

The survivor has also faced drug addiction and he has been hospitalized for several months in a rehabilitation clinic. This survivor told DRI that “I cannot deal with this any longer. I need to go to rehabilitate. It became worse after Pedro [a friend from “La Gran Familia”] hung himself. I had to pull his body down.”

In 2018, the CNDH issued recommendation 14VG/2018, which found serious violations such as physical and sexual abuse, forced labor, corporal punishment, medical negligence, and corruption of minors, among others, against the 536 children and adults who were detained in la Gran Familia. The CNDH found that the right to free development of the personality, health, education, personal integrity, identity, legal security, the right not to be trafficked, and access to justice were violated. The CNDH also highlighted the omissions by various authorities to duly protect the entire population –as there were signs of abuse for years. The case of La Gran Familia, and the survivor's painful testimony, demonstrates the human cost of institutionalization and lack of support and services in the community, including trauma- sensitive care.

VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN AND ADULTS DETAINED IN INSTITUTIONS

Article 10: Threats to the right to life

In the institutions we visited, DRI found that children and adults with disabilities are at a high risk of dying as a result of negligence, abuse, mishandling of restraints, degrading and unsanitary conditions (see Section on Article 15 on degrading conditions), and lack of adequate medical care.

The Mexican government does not report publicly on deaths in institutions. No independent investigations are conducted to determine why people die in institutions, and there is no official record-keeping on the death rate in these facilities. In four institutions DRI found a very high death rate: Casa Esperanza, Casa Gabriel, El Batán and Villa Ocaranza.

At Casa Gabriel, a private institution in Baja California that held 19 children and young adults with disabilities at the time of our visit, DRI found that five children and one young adult woman with disabilities (six people in total) had died in a period of four months, from November 2018 to February 2019. All those who died had been fed with feeding tubes. Staff confided to us that “complications” with feeding tubes were the cause of their deaths.38 Several children were also unaccounted for at Casa Gabriel. According to the coordinator of the institution, in 2017 there were 32 children with disabilities in the institution. When DRI visited the facility in February 2019, there were only 19 people with disabilities detained there. According to the staff of Casa Gabriel, two children were transferred and six had died – it is unclear what happened to the other children.39

The former President of the Developmental Disabilities Nurse Association –who has worked with children with disabilities in institutions for decades – observed that people in institutions are often maintained on feeding tubes unnecessarily for convenience of staff.40 Feeding tubes carry a risk for children and adults with disabilities, especially if managed improperly. Major complications include aspiration, intestinal perforation -that causes internal bleeding-, peritonitis, site infections, bloodstream infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, pneumonia and death.41 Other complications include tube dislodgement, tube leakage, intestinal blockages, pain, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea.42

According to DRI expert Marisa Brown, a registered nurse, enteral feedings should only be used after a careful review, ideally by a multidisciplinary team, that includes observation, metabolic analysis, and anthropometric measurement.43 Enteral feeding involves risks, particularly if the staff is not trained and carefully following protocols to ensure the tube is properly placed before each feeding. Problems include aspiration that can lead to death from pneumonia. In addition, DRI has observed children with feeding tubes left immobile in their beds, which is a serious cause of concern as forced immobility can increase the risk of severe constipation and intestinal blockages.

Medical recordkeeping is very poor in most of the psychiatric facilities DRI visited, and sot it would be nearly impossible to know the types of psychotropic medications that are commonly administered to persons with disabilities at the facilities. In many facilities there are no records of why patients are prescribed particular medications, or of side effects that patients may experience – much less individualized plans that would justify their use. Misuse of psychiatric medication can be fatal, especially in institutions where the standard of healthcare is low.

In the psychiatric institution El Batán in Puebla, the director told DRI investigators that 91 people with disabilities, almost one third of its total population, died over a period of two years. According to the director, “there were about 300 patients, right now there are 209, they have been dying.” The director told DRI investigators that the deaths were caused by the misuse of psychiatric medication combined with “other diseases” such as diabetes, hypertension, and other heart problems. Even taking into account possible health complications, a death rate of 30% in two years is approximately 10 times the mortality rate attributed to the use of psychotropic medications in other countries. Furthermore, the availability of appropriate psychotropic medications appears to be limited at El Batán; patients in the facility tend to be prescribed what is on hand, rather than what might be most effective.

In Villa Ocaranza, a public psychiatric institution in Hidalgo, the director of the institution told DRI that one of the main causes of death is choking, or as the director called it, “broncho – aspiration combined with antipsychotics.” There is extensive evidence that the use of high dosages of psychotropic medication can cause difficulty with swallowing. Instead of taking responsibility for the overuse of psychotropic medication and the failure to monitor their side effects, the director ascribed the large number of choking incidents to the fact that the detainees had disabilities. The director stated that “due to intellectual disability, patients struggle to swallow food and antipsychotic medication makes these symptoms worse.” Despite deaths due to choking at the institution, there were no swallowing specialists on staff, and no steps were being taken to mitigate the side effects of psychotropic medication.

According to DRI Marisa Brown, RN, it is possible to prevent further deaths:

An immediate consideration given that so many of the residents are experiencing dysphagia (most likely due to the use of antipsychotic medications) is for each person to receive a review of their mealtime patterns of behavior. Attention needs to be paid to the texture of the foods they are receiving, the availability of sips of water (including the viscosity of that water) during mealtime, their positioning, and the rate at which they are eating or being fed. Care must also be taken to ensure that for at a minimum of 30 minutes after each meal they are being positioned in an upright position to avoid gastroesophageal reflux. This set of procedures need to occur while each person is being evaluated for the possible careful titration of their psychotropic medications. This cannot be done too quickly in order to avoid the risk of tardive dyskinesia.”44

In the case of Casa Esperanza in Mexico City, one of the victims told DRI investigators that four children and adults with disabilities had died while on restraints at the institution. As described previously in this report, after DRI exposed the abuse and torture at the institution, the detainees were transferred to other facilities. DRI is aware that at least two of the thirty-seven survivors died within six months of being transferred to other institutions (see Section on “Emblematic cases”).

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) establishes that “every human being has the inherent right to life and [States] shall take all necessary measures to ensure its effective enjoyment.”45 Failure on the part of the Mexican State to guarantee that people with disabilities detained in institutions can effectively enjoy their right to life is in violation of Article 10 of the Convention.

Article 12. Denial of the right to legal capacity

Mexico’s legal framework does not recognize the right to legal capacity for persons with disabilities, failing to comply with Article 12 of the CRPD.46 Mexico’s Federal Civil Code establishes that people with disabilities have “natural and legal incapacity”47 and lays out a guardianship system that prevents them from directly exercising their rights on their own – instead, they have to do so through a guardian.48 By systematically stripping away the right and the ability of people with disabilities to make choices about their lives, Mexican law leaves people with disabilities at risk of improper detention, forced medication and treatment, and a myriad of basic decisions about their lives taken out of their control. Children and adults with disabilities in institutions are de facto and de jure stripped of their legal capacity. Mexico’s Civil Code automatically gives the guardianship of children to the institution that is housing them.49 In the case of adults with disabilities in institutions, a judge must appoint the institution as the guardian through a guardianship hearing.50 However, in practice, as DRI’s 2010 “Abandoned and Disappeared” report documented, people with disabilities detained in institutions are under the de facto guardianship of the institution and “automatically lose the right to make even the most fundamental daily decisions of life – with no legal process whatsoever.”51

Even more worryingly, state authorities often exercise a de facto guardianship over people in institutions, without bothering to go through the required legal processes to act as their guardian. In the case of Casa Esperanza, for instance, DRI found that child protection authorities (DIF) exercised a de facto guardianship over some of the adult victims without having been appointed as their guardian through a guardianship hearing.

The National Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN for its acronym in Spanish), in its “Protocol of action for those who provide justice to persons with disabilities,” states that judges must take into account the CRPD provisions and recommends that judges:

“refrain from continuing to approve new cases of guardianship of persons with disabilities, and adopt the decision-making support model, in order to stop the denial of their legal capacity and their freedom to make their own decisions.”52

On March 13, 2019, through Amparo 1368/2015, the SCJN established that the guardianship of people with disabilities is unconstitutional. This is an important step towards recognizing the right to legal capacity for people with disabilities in Mexico. However, the guardianship model will prevail until the Mexican legal framework, including its Federal and States’ Civil Codes, are harmonized with the CRPD and with the resolution of Amparo 1368/2015.

The CRPD Committee has made it clear that decision-making systems under national laws in which the will of a person with a disability is replaced by the will of a family member or guardian, known as guardianship systems, are contrary to the CRPD.53 In its evaluation of Mexico in 2014, the CRPD Committee expressed its concern “at the lack of measures to repeal the declaration of legal incompetence and the limitations on the legal capacity of a person on the grounds of disability.”54 The Committee urged the Mexican State to “take steps to adopt laws and policies that replace the substitute decision-making system with a supported decision- making model that upholds the autonomy and wishes of the persons concerned, regardless of the degree of disability.”55 Mexico’s continued failure to do so is in violation of Article 12 of the CRPD.

Mexico has also failed to create supported decision-making systems that replace guardianship regimes. Article 12 of the CRPD is one of the most innovative and important rights in that it recognizes the right of people with disabilities to make fundamental choices and exercise their “legal capacity” no matter what the level of disability or support needs of the individual.56 To the extent that an individual with a disability may have difficulty exercising his or her ability to make choices, CRPD Article 12(3) provides a right to the “support they may require in exercising their legal capacity.”

Article 13. Impunity and lack of access to justice

People who are living in institutions are arbitrarily detained (see Section on Article 14), segregated and physically unable to access legal remedies to challenge their detention and seek justice. They are also unable to personally and directly file for legal recourse because they are under the de facto guardianship of the director at the institution (see Section on Article 12). If a person suffers abuse in an institution, they would need to access judicial mechanisms through their guardian. Given that the director is the guardian, but also the person ultimately responsible for the abuses that take place at the institution, there is an inherent conflict of interest. Due to the fact that people detained in institutions are unable to directly and personally access justice, most abuses happening inside these facilities are not reported and remain in impunity.

The case of Casa Esperanza is a clear example of the impunity that prevails in cases where grave abuses were committed against persons with disabilities, even when they are reported. Over more than five years of complaints through official channels by DRI, public reporting,57 press coverage, and condemnation by the UN Committee on the Rights of People with Disabilities, the Mexican State has been made fully aware of the abuses and torture that occurred in the institution. They nonetheless knowingly and intentionally left the residents there, exposed to such abuse and mistreatment. The UN CRPD Committee specifically cited the case of Casa Esperanza and the problem of forced sterilization,58 yet Mexico has not changed its laws to prohibit the forced sterilization of other women with disabilities in its institutions.

The CRPD Committee also noted Mexico’s broad failure to create community-based services for people with disabilities. Despite the enormous publicity brought to these cases, the survivors of Casa Esperanza have not been provided community services because, according to government authorities, those services do not exist. People subject to torture, forced labor, and trafficking for sex at this facility have received no compensation for the abuse they suffered, and the underlying practices that allowed these abuses to exist still continue.

Moreover, no state authority has been prosecuted for the rape and torture committed against persons with disabilities at the facility. State authorities are responsible for the violations that took place in Casa Esperanza given that: 1) the institution was subcontracted to carry out activities on behalf of the State; 2) authorities have the obligation to monitor and supervise the conditions in institutions that provide services to persons with disabilities to prevent, stop, and investigate abuses; and 3) state authorities knew about the abuses and they have the duty to stop, investigate and prosecute violations that they know exist.

The DIF of Mexico City is representing the victims – acting as their de facto guardian (see Section on Article 12) – on criminal investigations that were opened against two staff members from Casa Esperanza. These criminal investigations have resulted in no convictions to date, more than five years after DRI complained to the authorities about the ongoing abuses at the institution. More importantly, the fact that no state authorities, and in particular no DIF officials, are being investigated for the grave omissions in this case exemplifies the conflict of interest between the rights of the victims and the DIF authorities acting as their representatives in the criminal proceedings. The lack of personal and direct access to justice by the victims results in a violation of their right to access justice under the CRPD.

DRI has been unable to monitor the situation of the survivors because the State has refused to let us know where they are and give us access to them, but what we do know is that at least two of the survivors have died and others are still being abused. The Mexico City Human Rights Commission has also denied DRI access to the case files, which we originally had access to as petitioners in the case brought by DRI. In order to regain access to the case file, DRI had to engage in a legal battle with the Commission and filed a complaint to the National Institute for Transparency (INAI by its acronym in Spanish.) In January 2020, the INAI ruled that the violations committed in the Casa Esperanza case are grave and as such, must be made available to the public, including DRI.

The case of Ciudad de los Niños, as we also mention in the Emblematic Cases section, has been fraught with impunity. In June 2017, a judge in an Amparo judgment found that there had been cases of serious sexual and physical abuse against the children detained in that institution by the priest running the facility, staff, and outsiders; there were also clear indications of pregnancies and possible trafficking of babies born at the facility and of children who had been sent there by government authorities. In spite of the gravity of the abuses, the Amparo

judgment was overturned by an Appeals Court,59 the priest was never criminally prosecuted, and has now been allowed to resume control of the facility. He has publicly stated that he plans to reopen it and has continued to run other institutions in Guanajuato and in Michoacán, a neighboring state. These cases show that grave abuses in institutions against children and adults with disabilities are not prosecuted and remain in impunity, violating their right to access justice.

Article 14. Liberty and security of the person

The total lack of any form of protection against arbitrary detention not only presents a threat to individual autonomy and freedom – it puts many peoples’ lives at risk. DRI encountered entirely unlicensed and unregulated facilities, described further below, that lock up dozens of men for substance abuse and psychiatric treatment. Government authorities are aware of these facilities and send person with disabilities for treatment there despite the total lack of any regulation or protection. One such facility, Fortalécete en Cristo in Baja California, relies on prayer and physical restraints rather than any form of medical treatment. It is located in a large house that was under construction when DRI visited, where open staircases with no bannisters and a lack of plumbing in some areas created health risks for detainees.

Detention of people with disabilities without their free and informed consent is allowed by Mexico’s laws and is a common practice in Mexico. Regardless of what the law says, DRI received numerous allegations that people were detained with no legal process based entirely on staff who deferred to the decisions of family members. These placements are widely considered voluntary because of family members’ consent – without any effort to determine the will and preferences of the individual whose rights -and life, are at stake. In addition, DRI observed many cases where the decision to detain a person was made by staff based on presumption medical or psychiatric necessity when family were not available to decide.

According to an official from the Ministry of Health’s Psychiatric Services (SAP by its acronym in Spanish), “80% of hospitalizations are involuntary.”60 Similarly, staff from the Yucatan Psychiatric Hospital told DRI that "most of the time, hospitalization is involuntary.” Given the lack of alternatives in the community (see Section on Article 19, right to community integration), hospitalizations in psychiatric facilities lead to indefinite institutionalization if the person has no supports or family in the community.

To the extent that detention is legally regulated at all, there are a patchwork of different protections in different states. In Mexico there are 14 states that have passed mental health laws after Mexico signed and ratified the CRPD.61 These mental health laws all, with the exception of the Baja California Mental Health Law, allow for the involuntary hospitalization and detention of people with disabilities.62 The General Health Law (hereinafter “LGS” by its Spanish acronym) and the Mexican Official Standard NOM-025-SSA2-2014 for the provision of health services in psychiatric hospitals (hereinafter NOM-025) establish that the person or their representative has the right to informed consent, except in cases of “involuntary admission.”63 Limiting the right to informed consent to cases of “voluntary” admission effectively invalidates this right.

NOM-025 further establishes that, in urgent’ cases, the user “can be admitted with the written indication of specialists […], and the signature of the responsible relative that agrees to the admission.”64 In theory , within 15 days of the admission, the person will be evaluated and the psychiatrist will assess the necessity of continuing with the detention.65 NOM-025 also states that “as soon as the conditions of the user allow it, they will be informed of their situation of involuntary internment so that, where appropriate, they can grant their free and informed consent and their condition can change to that of voluntary detention.”66

Staff at the 11 public psychiatric hospitals that DRI monitored told us that they involuntarily detain persons with disabilities, and, subsequently, they seek to change the status of their detention to “voluntary.”67 In practice, if a patient is admitted involuntarily and decides not to change their admission to voluntary, the patient remains institutionalized against their will. DRI visited the Federal Psychiatric Hospital Fray Bernardino Álvarez in Mexico City (hereinafter Fray Bernardino), where the director and psychiatric staff stated that they follow the NOM-025 guidelines. According to the Director, a person's consent is sought but if it is not obtained, they can be admitted against their will. After a few days, their consent is sought again, and in most of the cases, the director said that they “give it.” However, those who still do not give their consent remain detained.

The CRPD has established that the deprivation of liberty due to disability is discriminatory and incompatible with recognized international human rights standards. Article 14 of the CRPD establishes that “the existence of a disability shall in no case justify a deprivation of liberty.”68 The interpretation of the CRPD Committee is unequivocal: any involuntary and / or prolonged detention due to disability is contrary to the CRPD and should be considered unjustified and, therefore, arbitrary.69

Enrique’s case*

Enrique told DRI that he has been detained at the Fray Bernardino Álvarez psychiatric hospital for 6 months, against his will and for no apparent medical reason. His testimony was corroborated by hospital staff, who pointed out that “there is no medical reason for [him] to be here.”

Although he should not be hospitalized, Enrique cannot leave the hospital because he needs his sister's authorization. However, she has refused to sign for his release and get him out of there. Mr. Enrique expressed that his desire is to leave the psychiatric hospital. However, if his sister does not authorize his release, his only option is for his case to be brought by the hospital before a family court, who can then order the sister to authorize his release.

The fact that Enrique’s sister is given control over his case is in violation of his right to legal capacity (see Section on Article 12). Enrique is stripped from his right to make decisions over his life, including leaving the psychiatric hospital, and that decision-making power is given to someone else, in this case, his sister. This case is an example of how the denial of the right to legal capacity for persons with disabilities leads to their improper detention.

*Fictitious name to protect the identity of the person.