STILL IN HARM'S WAY: International voluntourism, segregation and abuse of children in Guatemala

Disability Rights International

Colectivo Vida Independiente de Guatemala

July 16, 2018

Authors:

Priscila Rodríguez, LL.M, Associate Director, Disability Rights International (DRI)

Laurie Ahern, President, DRI

Eric Rosenthal, JD, LL.D (hon), Executive Director, DRI

Lisbet Brizuela, MA, Mexico Director, DRI

Ivonne Millán, JD, Legal Advisor-Mexico, DRI

Dr. Matt Mason, Ph.D, Clinical Director, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development

Executive Summary

This report documents the human rights violations, exploitation, and trafficking of children with and without disabilities in Guatemala. Guatemala has failed to create the protections and support needed to help children live with a family – especially children with disabilities. DRI is also concerned that private charities and international donors are supporting orphanages and perpetuating discrimination. International support – including “voluntourism” – leaves children open to segregation, abuse, and further exploitation by traffickers.

In March 2017, 41 girls burned to death at the Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asunción orphanage (“Hogar Seguro”) in Guatemala. The girls had been protesting their rapes and forced prostitution at the hands of the staff at the facility. The protesters were locked in a room which was then set ablaze – and rescuers took nearly an hour to respond. The girls were silenced for speaking out about their abuse. Orphanage staff and government officials were arrested and charged with crimes.

Following the fire, Disability Rights International (DRI) joined the Guatemalan Human Rights Ombudsman in seeking immediate protections for the children living at the orphanage by bringing petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – to demand that the children be brought to immediate safety by returning them to families.

It is critical to note that globally, 80 to 95% of all children in orphanages have living parents and extended families. They are given up due to poverty and disability – families hoping their child will have a better life in an institution. In Guatemala, where 50% of children under the age of 5 years are malnourished, the lack of food pushes many children into orphanages.

Locked away and without the protection of family and community, children are at a much greater risk of exploitation and abuse. Sexual and physical abuse, trafficking for labor, sex and pornography have all been documented by DRI in orphanages around the world. International human rights law now protects the right of all children to grow up with a family.

In response to our petition to protect Hogar Seguro survivors, the Inter-American Commission ordered “measures to promote the reintegration [of the survivors of the fire] to their families, wherever possible.” The Commission also ordered Guatemala to provide “necessary supports” in the community so children with disabilities could return to family life.

A year after the tragedy, DRI has found that the survivors of Hogar Seguro – and children confined to institutions throughout Guatemala – are still living in harm’s way. Instead of investing in supports to protect families, Guatemala is doing the opposite – building new institutions to confine children. In addition, Guatemala has provided no public accounting for the whereabouts of hundreds of missing children following the chaos of the fire – who we suspect may have been trafficked into the sex industry.

Over the last year, DRI has conducted a broader investigation into children in Guatemala’s orphanages. The country’s child welfare system is built on a system of orphanages and institutions that separates children from their families and leaves them open to abuse and neglect. DRI’s investigation shows that conditions for children with disabilities are particularly dangerous. Children with disabilities who grow up in orphanages will likely remain in institutions for life. They may be transferred to psychiatric hospitals or nursing homes if they live to adulthood. Death is the only way they will ever leave an institution.

DRI has also documented extensive sexual abuse and trafficking at the country’s “Federico Mora” psychiatric facility for adults. Despite publicizing abuses at “Federico Mora” for over seven years and winning orders for precautionary measures from the Inter-American Commission to protect the “Federico Mora” population, abuses persist. Unless Guatemala takes action to close “Federico Mora”, children with disabilities who grow up in the country’s orphanages may well end up in this abusive facility.

In Guatemala, we have found serious and pervasive abuses even in newly built facilities that have received government and international funding. DRI observed hundreds of children tied to wheelchairs and furniture and locked in cages. In some facilities, their heads are shaved, they do not go outside, and they languish in inactivity.

The government spends 45 times as much, per child, to lock them up than it does to help a family keep a child with a disability at home.

Children without disabilities confined to institutions are also at great risk. Children who “graduate” from orphanages around the age of 17 have little or no skills to face life on their own. International experience shows that, with no family or community to support them, the risk of suicide, drug addiction, sex trafficking, criminal activity, and death is many times higher than that of children who grow up with a family. In a country that permitted widespread trafficking to occur at Hogar Seguro, there is every reason to believe that trafficking would be taking place in other institutions as well.

This continued abuse is completely avoidable, as good models do exist in Guatemala. For $10 to $60 USD/month, the Hope for Home program has demonstrated that it can help children with and without disabilities live at home and avoid confinement in institutions.

While children desperately need support to return to and grow up with their families, international funding and international volunteers are perpetuating segregation and abuse by supporting Guatemala’s orphanage system. In addition to funding more than 100 private institutions, foreigners pay substantial sums to have the opportunity to “help” orphans. Most volunteers do not realize that the vast majority of children in orphanages are not orphans – they are given up by desperate mothers and fathers who cannot afford to feed or clothe their children.

“Institutional care in early childhood has such harmful effects that it should be considered a form of violence against young children.” – UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

At the Hope of Life orphanage, in a remote area six hours outside Guatemala City, Hogar Seguro survivors languish in barren rooms with few activities and little to do. The volunteers’ quarters look like a resort, with several swimming pools, a zoo with lions and tigers, and large dining areas where they are offered a buffet for their meals. For $1,000 a week, guests stay in a 4-story building with air-conditioned luxury rooms surrounded by an artificial lake. The children do not have access to these beautiful facilities.

In addition to survivors of Hogar Seguro, many of the children in the Hope of Life orphanage are placed there so they can use the “nutritional hospital. These children come from poor villages high in the mountains where they do not have enough food. Instead of feeding these children at home, the institution separates them from their mothers and fathers. Some children never return to their families, losing their parents in exchange for the nutrition they need to survive.

DRI investigators also visited Dorie’s Promise, an orphanage where volunteers pay $1,100 to volunteer for a week. The website of this facility offers foreigners the opportunity to sponsor a child at $750/month – a rate that is six times the monthly income of a lower middle-class family in Guatemala. Despite the flow of money and volunteers, DRI investigators observed children living in overcrowded 18-bed houses. In a visit of more than one hour, we saw children with no adult attention being visibly aggressive with one another.

An extensive body of research has shown that children need to form loving and stable emotional attachments to family in order to grow up healthy and avoid the emotional damage of attachment disorder. Orphanages where volunteers come and go provide children with the opposite of such an environment. They grow up without family, and they form attachments to volunteers who may be gone from their lives within days. DRI investigators saw the outward signs of attachment disorders in many of the institutions where we visited: children who asked “are you my new mommy?” – unable to distinguish between real family and a passing visitor.

There is an intersection between voluntourism and child sex tourism as volunteers have unfettered access to children and criminal background checks are only occasionally done. Some orphanages even allow volunteers to sleep in the same room as the children.

International human rights law now recognizes the right of all children to grow up with a family – and not in an institution. The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has recognized that children face an increased risk of abuse and torture whenever they are placed in an institution. Due to the dangers of placing any child in an institution, the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) called on Guatemala to stop any new placements in orphanages.

"The Committee notes with concern that the limited funding sourced from international cooperation is frequently used to finance institutions where children and adults with disabilities are permanently segregated and that many such institutions are sustained by the growing trend towards voluntourism in Guatemala.”[1]

In a country in which children are placed in orphanages because families cannot afford to keep their children, even small donations to orphanages help perpetuate a system that contributes to the break-up of families. The CRPD Committee has made clear that it is the responsibility of the government of Guatemala to ensure that international funding is used to protect families rather than institutions.

The limited government funding that is being used to support children with disabilities is also being misused to support newer, smaller institutions. In its observations, the CRPD Committee also noted that “[f]or children, the core of the right to live independently and be included in the community entails a right to grow up in a family.”[2] The CRPD Committee goes on to explain that:

“Large or small group homes are especially dangerous for children, for whom there is no substitute for the need to grow up with a family. ‘Family-like’ institutions are still institutions and are no substitute for care by a family.”[3]

Guatemala should avoid investing in smaller new institutions or group homes – and it should not follow-through on plans to reopen Hogar Seguro that would serve as a center to confine children.

The Hogar Seguro tragedy brought world attention to the concerns of children in Guatemala’s institutions. Guatemala should use this attention to start a fundamental reform process, to move away from its history of confining children and create a new system of support for families.[4] The government should use its own funds – and the generous assistance of international donors – to ensure that every child has an opportunity to live and grow up with a family.

Table of Contents

- I. Background & Purpose

- II. Institutionalization of Children

- A. Dangers of institutionalization: the case of Hogar Seguro

- B. Situation of Hogar Seguro survivors with and without disabilities

- C. Institutionalization due to lack of supports for poverty and disability

- D. Abuse and torture for children with disabilities

- E. Infanticide

- F. Arbitrary judicial orders for confinement of children

- III. How funding perpetuates segregation and abuse

- IV. Legal Standards and Recommendations

- A. Put a moratorium on new admissions

- B. Support Deinstitutionalization

- C. Support families and kinship care – not small institutions or group homes

- D. Strengthen foster care

- E. Support participation by stakeholders – including children’s rights and disability groups

- F. Ban International Funding of Institutions and Orphanage Voluntourism

- G. Investigate disappearances and publicly account for all survivors of Hogar Seguro

- H. Human rights oversight and anti-trafficking programs should monitor all public and private programs for children

- I. International donors & volunteers must support reform – not perpetuate further abuse

- APPENDIX 1

Abbreviations

ABI - Centro de Abrigo y Bienestar Social

ACHR - American Convention on Human Rights

CRC - Convention on the Rights of the Child

CNA (for its Spanish acronym) - National Council of Adoptions

CRPD - Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

DRI - Disability Rights International

IACHR - Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

CRPD Committee - Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of the United Nations

MP (for its Spanish acronym) - Public Prosecutor

PDH (for its Spanish acronym) - National Human Rights Ombudsman of Guatemala

PGN (for its Spanish acronym) - Attorney General's Office

SBS (for its Spanish acronym) - Minister for Social Welfare of the Office of the President

I. Background & Purpose

Disability Rights International (DRI) has been active in advocating for the rights of children and adults with disabilities in Guatemala for more than seven years. Our first investigation focused on the rights of children and adults detained at the “Federico Mora” psychiatric institution. We have documented pervasive inhuman and degrading conditions at that facility that amount to torture, including dangerous and unhygienic conditions of living, the dangerous use of physical restraints and isolation, lack of medical and psychiatric care, violence and sexual abuse, and trafficking for sex. DRI filed a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) demanding immediate, live-saving protections for that facility’s 300 detainees (see DRI’s findings and petition). In November 2012, the IACHR issued an order for “precautionary measures” to call on Guatemala to end severe and irreversible abuses at that facility. As a result of the order, criminally convicted detainees and the armed guards watching over them have been moved to a separate section of the facility. In addition, DRI has no longer found children detained at “Federico Mora”. DRI’s recent investigations in 2018 have found, however, that ill-treatment and abuse continue. DRI has called on Guatemala to create a community-based service and support system for people with psychiatric and intellectual disabilities and to stop new admissions of adults to this dangerous facility. Despite many promises to do so, Guatemala has failed to create the protections and social services necessary to stop admissions to “Federico Mora”.

In addition to documenting abuses at “Federico Mora”, DRI has broadly examined the protection of children and adults with disabilities in orphanages and other social services throughout Guatemala. DRI is concerned about the rights of all children confined to institutions, because the placement of any child in an institution can lead to emotional damage and developmental delays.[5] Various studies show that the psychosocial deprivation inherent in institutions profoundly affects the emotional, cognitive,[6] physical and psychological[7] development of a child and “leads to lifelong problems in learning, behavior and health.”[8] According to the report on World Violence against Children of the United Nations:

“The effects of institutionalization can include poor physical health, severe developmental delays, disability, and potentially irreversible psychological damage. The negative effects are more severe the longer a child remains in an institution, and in instances where the conditions of the institution are poor.”[9]

The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has found that placement of children in an institution exposes them to violence and abuse – and an increased risk of torture.[10]

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities protects the rights of all people with disabilities to live in the community – no matter what their level of disability. In 2013, UNICEF called for governments around the world to “end institutionalization” of children.[11]

In August 2016, DRI filed a report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) about our findings regarding children in Guatemala. In September 2016, the CRPD Committee asked Guatemala to “abolish institutionalization” of children.[12] The Committee, which was established to evaluate governments’ compliance with the CRPD, appears to endorse a moratorium on any new placement of children in orphanages or other institutions. The UN CRPD Committee also called on Guatemala to regulate the use of international funding and volunteers to ensure that the rights of children are protected.[13] This report evaluates compliance with those important recommendations for the protection of children’s rights.

In 2017, DRI learned of findings by the Human Rights Ombudsman of Guatemala that abuse and trafficking was taking place at the “Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asunción“(hereinafter Hogar Seguro) orphanage. DRI sent a team to investigate. On the day our team arrived, there were riots at the facility of children who were protesting their own rape and forced trafficking. We were unable to enter Hogar Seguro that day. The next day we learned that 41 girls who were protesting at the facility were locked up and died in a fire. DRI conducted an immediate investigation into the conditions of the survivors, and we issued a report in March 2017, After the Fire: Survivors of Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asuncion at risk: Findings and Recommendations for Action.

DRI joined the Human Rights Ombudsman of Guatemala (PDH for its Spanish acronym) in demanding immediate rights protections for children at Hogar Seguro through a petition to the IACHR. The IACHR granted our petition and ordered Guatemala "to promote the reintegration [of the survivors] to their families, whenever possible and with the necessary support, or identify alternative care that is more protective."[14]

In addition to broadly examining the right of children confined to Guatemala’s institutions, this report is a one-year follow-up to our After the Fire report and examines Guatemala’s compliance with the order of the IACHR. This report is not intended to evaluate the investigation and criminal prosecution of individuals involved in abuses at Hogar Seguro. However, there are reports that these prosecutions have been inadequate.[15] On March 8, 2017, the Minister for Social Welfare at the time of the fire, Carlos Rodas, stated in a press conference that the President of Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, had ordered the Chief of Police to enter Hogar Seguro and “guard two dormitories,” one of which was the auditorium where the 56 girls were locked up as a form of punishment.[16] Activists in Guatemala have questioned the President’s motives in making such an order, since the police have been accused of complicity in delaying life-saving help for the girls.[17]

In addition, the Attorney General has been accused of failing to adequately investigate and report on the allegations of trafficking at Hogar Seguro. In November 2016 –four months before the fire- the PDH filed a complaint before the Attorney General for 4 cases of pregnancies at Hogar Seguro, where trafficking was suspected.[18] However, by May of this year -almost two years later, the PDH had not “heard anything” regarding the investigation, despite requesting information to the Attorney General.[19]

DRI calls for a full investigation of these allegations. This report, however, is primarily focused on the immediate human rights concerns facing survivor – as well the rights of all children who remain at-risk because they are confined to institutions throughout Guatemala. The report evaluates Guatemala’s compliance with international human rights laws that it has committed itself to enforcing through the ratification of international treaties. This includes the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR). While DRI is especially concerned about the rights of children with disabilities, we also examine the rights of all children under international human rights law.

Institutions visited: Since March 2016, DRI has visited 13 institutions for children (7 public and 6 private), interviewing staff and, where possible, the children at each institution. We have especially focused on monitoring conditions of the survivors from Hogar Seguro who have disabilities. To this end, we have visited 11 public and private institutions where survivors have been placed. The facilities visited by DRI include the following public institutions: Alida España, Centro de Abrigo y Bienestar Social (ABI), Ónice I and two “residential centers” in Zones 1 and 3 I in Guatemala City, and Ónice II, Ónice III and Nidia Martínez in the city of Quetzaltenango; and the private institutions: Hope of Life, Dorie’s Promise and Hope for Home. DRI also visited Virgen del Socorro Obras Sociales del Hermano Pedro and Fundación Albergue Hermano Pedro, two institutions in Antigua, Guatemala, that house children with disabilities.

II. Institutionalization of Children

A. Dangers of institutionalization: the case of Hogar Seguro

According to UNICEF statistics from 2013, there are 5,474 children institutionalized in Guatemala. Of these, 1,925 children are placed in public institutions and 3,549 children reside in institutions registered as private.[20] The total number of children in institutions could be much higher due to the existence of unregistered institutions.[21]Up to ninety five percent of children in institutions have families.[22] These children end up in institutions because there are no supports for families living in poverty or with children with disabilities, or because they are removed from their families without first seeking alternatives in the extended family or in the community.

DRI’s investigation in Guatemala over the last year has not found significant improvements in the country’s human rights oversight and enforcement, its child protection system, or its community-based social services and mental health programs that might help prevent abuses of the kind that took place at Hogar Seguro. The case of Hogar Seguro demonstrates the risks that children face when they are placed in any institution in Guatemala.

Hogar Seguro is a public institution located in San José Pinula, in Guatemala. As of March 2017, there were very likely more than 700 children detained at the institution,[23] 173 of which had a disability.[24] On March 8, 2017 there was a fire in the institution that killed 41 girls. The day before the fire “104 girls mutinied and managed to escape from the shelter.”[25] According to reports, the girls were protesting rape, forced prostitution, and trafficking by staff at the institution.[26] “The girls ran out of patience after complaints filed for abuse and rape since 2015” yielded no effect.[27] The police located the majority of the girls who had escaped and, “as a disciplinary measure, 56 girls were locked in a classroom smaller than 44 square meters.”[28] In the early hours of the morning, the teenagers asked staff to open the door to go the bathroom, but their request was denied. After this, a fire started that killed 41 of the 56 girls and left the rest severely injured.[29]

The children who were detained at Hogar Seguro ended up in the institution for various reasons including abandonment and disability. Several of the children were sent there as a protection measure, including girls who were rescued from criminal gangs that are alleged to have sexually exploited them.

Many families have reported that they sent their children to the institution to keep them away from criminal gangs.[30] This was the case of Lucia, a teenager who was reported to have been sent by her mother to Hogar Seguro because she was harassed by a group of gang members from her neighborhood. Her mother decided that the best option to “protect her” was to institutionalize her.[31] Ironically, children who were sent to Hogar Seguro to protect them from sexual abuse, harassment and gangs found exactly that at the institution.

Several children were sent to Hogar Seguro by court order. However, in many cases, the decision to remove them from the family environment was made without exploring alternative measures to keep the child in their family and community. Virgilio López, father of Keila, a 17-year-old girl who died in the fire, told the media that Keila’s mother, his former wife, was the one who took her to Hogar Seguro because she was a ‘rebel.’ Her father got Keila out of the institution and took her to live with other relatives. However, his sister-in-law filed a criminal complaint against Keila after a dispute with her cousin. Keila and her father appeared before the judge, who determined that returning Keila to Hogar Seguro was the best option. “I cried to the judge and I pleaded with her to leave Keila with me, but the judge said that Keila would be better in the institution."[32]

It is worth noting that before the fire, Hogar Seguro received international condemnation from the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 2010, when the CRC issued a recommendation to investigate the institution.[33] Despite allegations of violence and trafficking of the children,[34] well-meaning international volunteers continued to visit the facility[35] bringing gifts and donations, further supporting the institution.

Immediately after the fire, as documented by DRI in our After the Fire report, surviving children with and without disabilities were transferred to other institutions. One year later, according to the Minister for Social Welfare, 180 of the original survivors remain in institutions. Of these, 120 are considered by the authorities to have disabilities. DRI visited the following public institutions where the survivors of Hogar Seguro have been transferred to: Abrigo y Bienestar Integral (ABI), Alida España, Ónice I, Nidia Martínez, Ónice II, Ónice III, and two “residential centers” in Zone 1 and 3; and the private institutions Dorie’s Promise, Hope of Life and Hope for Home.

In the autumn of 2016, the Human Rights Ombudsman reported to the Inter-American Commission that there were 800 children at Hogar Seguro. The government claims that there are 600. The Human Rights Ombudsman and DRI have sought a full accounting by the government of all survivors, but the government has failed to do so. According to the authorities, 223 were sent back to their families. One teenager has reportedly been integrated in a foster family.[36] According to the Minister for Social Welfare, 130 teenagers have turned 18 since the fire and, thus, are no longer part of the child protection system. According to the Minister for Social Development, there are still 180 children in institutions.[37] The numbers provided by government authorities do not add up exactly to the 600 they have acknowledged were at the facility. UNICEF has recognized that 33 children and teenagers are missing and an alert was activated to find them.[38]

In addition to our concern about children who have been placed in institutions, DRI is deeply concerned about children who have been supposedly returned to families. If children were taken from families because of abuse or dangerous conditions originally, have efforts been made to ensure their safety? Given the widespread trafficking that was known to have taken place at Hogar Seguro, DRI is concerned that children unaccounted for may have been turned over to or exploited by traffickers.

Intervention by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): On March 12, 2017, in response to a petition submitted by the Human Rights Ombudsman, the IACHR issued an order for precautionary measure to protect survivors of Hogar Seguro.[39] The IACHR urged Guatemala to take "effective measures to promote the reintegration [of the survivors] to their families, whenever possible, with the necessary supports."[40]

DRI’s investigation has shown that, despite this order from the IACHR, Guatemala has been creating new institutions for survivors with disabilities. In a working meeting held between the State of Guatemala, the petitioners of the precautionary measures – PDH and DRI – and the IACHR in September 2017, the Guatemala reported that they had plans to reopen Hogar Seguro. With funding from the US government, Guatemala is now reopening Hogar Seguro as a “Specialized Reinsertion Center” of minors who were deprived of their liberty and are turning 18.[41] It is not clear whether this “reinsertion center” will be a residential institution or whether it will include children. DRI urges the State and the US government not to finance residential institutions for children of any kind. Most important, the Government of Guatemala must ensure – and donors must confirm – that direct care staff, guards, or authorities responsible for Hogar Seguro any other service program have no history of complicity with exploitation or abuse of children.

B. Situation of Hogar Seguro survivors with and without disabilities

Institutionalization and segregation

At least 180 survivors of Hogar Seguro remain institutionalized. Since the fire, a new institution for children with disabilities has been established called Nidia Martínez. This institution has a capacity for 80 children. There are 35 children with disabilities from Hogar Seguro currently living there, but it has the potential to admit many more. At least four more residential centers have been established for children without disabilities. These “residential centers each have up to 35 children in them.

Guatemala has also created three group homes for children with disabilities. These are clearly intended as a more humane alternative to the larger, older orphanages. However, experience from research has shown that there is no substitute for a child growing up with a family. Smaller institutions and group homes are inherently detrimental to the growth and development of children.[42] As the CRPD Committee has stated: “[l]arge or small groups homes are especially dangerous for children, for whom there is no substitute for the need to grow up with a family. ‘Family-like’ institutions are still institutions and are no substitute for care by a family.”[43]

In the course of our investigations, DRI visited three new group homes, including Ónice II, which houses 16 children and teenagers; Ónice III, which houses 20 young adult; and Ónice I, which houses 8 young women.

While group homes of any size are not acceptable for children, these three facilities would be large even for adults. Research on adult facilities has shown that larger group homes have more institution-like, impersonal, and regimented conditions – and are associated with lower quality of live and levels of social functioning.[44] There is a strong drop-off in outcomes among any group home larger than six adults.[45] These “group homes” for children are much larger than would be optimal even for adults. In practice, these are small institutions for children.

The Nidia Martinez institution and the three group homes have many of the impersonal conditions that are typical of institutions – including rules and regulations that apply to all children, not tailored to their individual needs. Dr. Matt Mason, who participated in visits to these institutions, observed that all the children he encountered could easily, with the necessary supports, live in the community.

Continued risk of trafficking

The Attorney Generals’ Child Protection Unit found that the number of children and teenagers that have “escaped” institutions –including so called “residential centers” that Hogar Seguro survivors have been transferred to- has quadrupled this year, compared to last year.[46] Given the “alarming increase” in “escapes,” the PDH fears that the children and teenagers that are “escaping” are actually being victims of trafficking.[47] According to the PDH, teenagers who are constantly escaping are particularly at risk of trafficking as it is believed that they could be pressured to escape and “be recruited by adults for organized crime groups.”[48] The PDH has requested the Attorney General to investigate the possible links to trafficking. However, the PDH regretted that the Attorney General “is only investigating the allegations of abuse perpetrated by staff, and not the possible trafficking that is happening in these residential centers.”[49]

Isolation of minors

In one of the “residential centers” that DRI visited in Zone 1, in Guatemala City, DRI found a teenager survivor of Hogar Seguro in isolation. The place used to be a drug rehabilitation center for teenagers. He was trying to escape the conditions in which he is kept (see Section B.5). The staff’s response was to lock him in a “patio.” Staff admitted that they do not have the resources to deal with the children and they do “what they can with what they have.” During DRI’s visit, which lasted over half an hour, the teenager remained isolated, at times holding his head on his hands, at times shouting and kicking the door.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has indicated that isolation represents in itself a form "of cruel and inhuman treatment, harmful to the mental and moral freedom of the person and the right of every detainee to have its inherent dignity respected." [50] On the isolation of children, Juan Méndez, former Rapporteur on Torture, stated that "the imposition of the regime of isolation on minors, whatever their duration, is a cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or even torture.[51]

Physical abuse

On April of this year, several survivors of Hogar Seguro escaped the “residential center” they had been moved to, in Zone 15, in Guatemala City. They alleged physical abuse from staff.[52] According to a reporter covering the scene, one of the teenagers had a visibly bruised face and when interviewed stated that “two staff beat me. They make me pick up trash, I got tired and they beat me up.”[53] By May of this year, the Ministry for Social Welfare had filed six cases before the Attorney General in which staff is accused by teenagers of physical abuse.[54]

Inhuman and degrading conditions

In Guatemala City, DRI visited two “residential centers” for survivors of Hogar Seguro. One “residential center” in Zone 1 had only two boys when DRI visited it. The morning of DRI’s visit, eight teenagers had escaped. According to staff, the survivors do not like being locked up, so they leave. In this institution, DRI found windows without glass; metals bars sticking out improvised fences to block windows and doors; exposed electrical wires; mattresses in bad state and dirty bathrooms.

In the second residential center visited by DRI for survivors of Hogar Seguro, we found 28 girls. According to staff, in the last few weeks, 7 girls have escaped. There was trash accumulated in one of the “patios,” there were electrical cables exposed and the girls only had running water twice a week. The rest of the days, they have to keep water stored in buckets. The place has been deemed unsuitable by the Ministry for Social Development, who vowed to move the girls to a more adequate institution since April 26.[55] Two months later however, the girls remain in the same conditions.

Lack of adequate care and mental health support

Guatemala’s Minister for Social Welfare acknowledged to DRI investigators that the institutions to which the survivors were transferred lack medical staff.[56]DRI investigators also observed a lack of basic care staff at most facilities, and a lack of any mental health treatment that children who have survived a traumatic experience may need.

These institutions are the last place you would want to put a child who survived trauma. These chaotic and unsafe environments only contribute to childrens’ suffering and long-term mental health problems. – Dr. Matt Mason, Georgetown University.

Children who experienced violence and lost friends in the fire at Hogar Seguro have all experienced serious emotional trauma. Officials from the Ministry of Social Welfare stated that there are no trauma specialists at any of the programs serving children who survived the Hogar Seguro fire. For survivors of Hogar Seguro, access to complex medical or psychiatric care may not be as crucial as the emotional support and safety of a family.

At Nidia Martínez, the 80 bed institution established for Hogar Seguro survivors with disabilities, the majority of the staff comes from Hogar Seguro. Given the level of abuse and violence reported at Hogar Seguro, the very presence of this staff may be re-traumatizing for children in this facility. The staff responsible for educating the children with disabilities were not qualified to do so, with the majority having no higher education. Nidia Martínez staff mentioned that caregivers perform all kinds of activities, from washing clothes and cleaning to supervising and ‘educating’ the children with disabilities.[57]

As Hope of Life, DRI found two caregivers per room, with each room housing around 11 children. Some of the staff were secretaries of the Ministry for Social Welfare and were sent to the institution due to a lack of staff.[58] The secretaries did not have any interaction with the survivors. DRI observed a child who tried to leave the room but was stopped by the staff, leading him to cry and hit himself. The staff's solution was to sit him in a high table, so he would stop trying to go out "since he was afraid to get down on his own." The boy stayed sitting in the table and continued to cry and hit himself.

Survivors of Hogar Seguro at Hope of Life

At Dorie’s Promise, a private institution, staff is not involved with the children; during our visit they were engaged in other activities such as cooking and washing clothes. There were volunteers at the institution who expressed that the staff often looked "exhausted."[59] In this facility, DRI found two children with disabilities. When we arrived at the institution we found one of them locked in a room by himself. The two children with disabilities did not participate in the activities that the staff and volunteers organized for the rest of the children, including attending school. At Hope for Home, DRI found two staff caring for 11 children in one house. The house was in an abandoned state, there were dirty clothes on the table, the rooms were not clean, and the house was not fully accessible.

Re-victimization due to multiple transfers

All of the Hogar Seguro survivors with disabilities have been transferred to different institutions at least twice since the fire. Each transfer can be emotionally difficult for children, as they lose connections with the only people they know. This is especially serious for children with intellectual disabilities and children who have experienced emotional trauma. Research has shown that “transfer trauma” is associated with emotional damage.[60]

Carlos[61] (see section II. 3) is a child who has been moved between institutions at least 4 times since he left Hogar Seguro. The first transfer was to the public institution ABI on March 9, 2017. In its report After the Fire, DRI found inhuman and degrading conditions for the survivors of Hogar Seguro at that institution. After our report, Carlos and the rest of the survivors who were at ABI were transferred to other institutions. Carlos was transferred to Alida España, but then, in March 2018, he was transferred back to ABI. A few days later he was moved again, to an institution for women with intellectual disabilities that is not 100% accessible. According to the Ministry of Social Welfare, efforts are being made to move Carlos yet again, this time to the newly inaugurated public institution Nidia Martínez in Quetzaltenango, a city that is four hours away from the capital. Carlos's mother lives in Guatemala City. Moving him to another city would take him further from his family and make his reintegration process even more difficult.

According to the psychologist in charge of Carlos’s case, the constant changes in staff and institutions have deeply affected his emotional and mental wellbeing. In the words of the psychologist:

[Carlos] has deteriorated in the past months, he has stopped smiling. He was a dynamic child, he smiled, and he talked, and talked. […] He does not want to eat, he used to hold the spoon and now staff has to spoon feed him, he has been losing strength in his muscles, his language has deteriorated too, he used to hold a conversation, now he does not want to talk. When he was in Alida España he received special education services, which allowed him to socialize more with other people and talk more. He is not receiving those services anymore.[62]

The IACHR has established that "it is necessary to keep changes and transfers to a minimum, always providing for the establishment of adaptation processes that ensure the participation of the children and adolescents and taking their best interests into consideration."[63]

C. Institutionalization due to lack of supports for poverty and disability

Poverty

Many families in Guatemala are forced to give up their children because they lack the funds to feed and support them. UNICEF classifies Guatemala as a low/middle income country.[64] But poverty itself is not necessarily associated with high levels of institutional placement.[65] In fact, extensive findings from research around the world have demonstrated that supporting families to keep their children is much less costly than placing children in institutions.[66]

In the Guatemalan context, the government is more likely to separate a child from their family due to issues related to poverty, than to provide the family the supports and guidance they may need. The separation of children from their families by the Guatemalan state due to poverty has in fact set a precedent in international jurisprudence. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights recently ruled in the case of Ramírez Escobar and others v. Guatemala that "the decision to separate the Ramírez brothers from their biological family was based on discriminatory justifications about the family's economic situation [...]."[67]

Disability

Lack of support for families of children with disabilities is also a major factor behind the institutionalization of children. In its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of the State of Guatemala, CRPD Committee expressed its alarm "at the high rate [...] of institutionalization of children with disabilities."[68] According to the World Report on Disability, "people with disabilities may have extra costs for personal support or for medical care or assistive devices. Because of these higher costs, people with disabilities and their households are likely to be poorer than non-disabled people with similar income."[69]

Disability coupled with poverty and lack of supports puts children with disabilities at risk of being institutionalized. The director of Hope for Home, a private institution for children with disabilities, mentioned to DRI that several children are in the institution because their families do not have the resources to take care of them. Juan, a child who lives in the institution, was reintegrated with his mother; however, he became severely ill three times in one month and his mother could not afford to take care of him, so he was returned to the institution. [70]

A social worker from Obras Sociales del Hermano Pedro, an institution in Antigua, told DRI that most of the children in the institution come from very poor families who do not have the resources to take care of them and cannot afford their medical expenses; "families prefer to have them here so they can have medical treatment.”[71]The case of Carlos, a survivor of Hogar Seguro with a disability (see section II.3), exemplifies how the lack of supports for poor families with children with disabilities is a major factor behind the institutionalization of children. Carlos's mother was too poor to take care of him so she took him to an institution. Paola,[72] another survivor with disabilities from Hogar Seguro, has a family. However, Paola’s family cannot pay for her medication, [73] and because all her family members must work, there is no one who can take care of her full-time; therefore, she remains institutionalized.

All these cases demonstrate that children with disabilities are institutionalized because of poverty and lack of supports. Article 23(3) of the CRPD establishes that States have the obligation to provide “information, services and supports” to children with disabilities and their families. This support is to be given in an “early and comprehensive” manner with a view to guarantee the right of children with disabilities to “family life” and in order to prevent “abandonment, neglect and segregation”[74] – an implicit acknowledgment that lack of support may lead to abandonment and segregation.

CRPD Article 23(5) establishes the most important protection of the right to grow up in a family,[75] stating that governments shall, “where the immediate family is unable to care for a child with disabilities, undertake every effort to provide alternative care within the wider family, and failing that, within the community in a family setting.”[76] Thus, if a child must be temporarily or permanently separated from his parents, Article 23(5) makes it clear that the child still has a right to grow up in a family environment with extended kinship care or in a substitute family. It is worth noting that Article 23(5) “never allows for the possibility of placing a child in an institution or in any form of residential care.”[77]

Lack of family support

Children with disabilities and their families need support. The government of Guatemala currently provides Q. 500 (USD $70) to some, but not all, families of children with disabilities.[78] This cash transfer is not enough for families with children with more severe disabilities, which indicates that cash transfers need to be flexible to adapt to the family’s needs. In addition to this support, families should be able to access services near them. Heavily centralized services, which is the reality in Guatemala today, mean that families must travel long distances to access them, which is a time and financial burden – some families spend more than the USD $70 cash transfer on transportation alone.[79]

The private institution Hope for Home has a community program that supports 150 families with children with disabilities. This program demonstrates that an array of basic supports tailored to the family’s needs and provided in the community can make the difference between life and death and between a life of institutionalization and a life in the community for children with disabilities and children who come from very poor families.

The director of Hope for Home told DRI that the financial support provided to families ranges from USD $10 USD to USD $60, depending on the family, their needs, and the frequency of support required. The type of support provided to each family varies – some families may need support with medications, diapers, food, or formula, while others need access to therapies at home and personalized support. Hope for Home also connects families with people in the United States who want to support by “sponsoring” a child and his family.

DRI visited two families supported by Hope for Home. Family 1 lives in conditions of extreme poverty, in a house with only two rooms and a patio. Two adult women and seven children, including a baby with a disability, sleep in the rooms. The mother of the baby with a disability is 19 years old. The director of Hope for Home told DRI that the initial support this family requires includes: groceries twice a month because the whole family is malnourished, special formula for the baby with a disability, medical appointments with different specialists, and a therapist that can go to their home. The director of the organization estimated that this type of support could cost around $60 USD per month.

Family 2 lives in poverty and has a 13 year old child with physical and hearing. The family has been a beneficiary of the Hope for Home family program for the past six years. The organization has provided support intermittently to the family, depending on their needs. The last time they received support from the organization was November 2017. The family now needs support again to cover school expenses, hearing aids, and orthopedic devices.

Supporting a child in their family is cheaper than detaining him in an institution. The state is spending at least 15 times the amount that Hope for Home provides to families in the community to keep children in institutions.[80] Supporting children with disabilities in their families is not only cheaper, but it is also necessary to protect their life and their physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing, and thus protect and guarantee their rights to live in the community and a family, as recognized by the CRPD (Articles 19 and 23) and the CRC.

The cost of supporting children with and without disabilities in the community and their families in the long term is also cheaper for the state. Most children leave institutions when they turn 18, but those who have a disability remain in institutions for life, and the state must pay for the institutionalization.

For those children who leave institutions, the impact of having deprived them of their liberty may be invisible because of the psychological damage it causes.[81] The Former Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment notes that chief among such adverse psychological impacts are “higher rates of suicide and self-harm, mental disorder, and developmental problems.”[82] The European Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights drew from research in Russia showing that “one in three children who leave residential care becomes homeless; one in five ends up with a criminal record; and in some cases as many as one in ten commits suicide.”[83] This creates a public health and public security cost for the state long term.

Hope for Home is also starting a pilot project where microcredits are offered to families with children with disabilities. In this project, five families have received financial support ranging from USD $150 to USD $450 USD so that they can generate a source of income. Given the conditions of extreme poverty in Guatemala, it is important to generate sustainable models such as this that include people with disabilities and their families and contribute to breaking the cycle of poverty in which they are currently living.

D. Abuse and torture for children with disabilities

Children with disabilities who do not receive the supports they and their families need are at risk of being institutionalized, neglected, abused, and tortured. DRI visited two private institutions for children with disabilities: Hogar Virgen del Socorro, Obras Sociales del Hermano Pedro (hereinafter “Virgen del Socorro”) and Albergue del Hermano Pedro, both in Antigua, Guatemala. In both institutions children face abandonment, inhuman and degrading conditions, and abuses that can constitute torture. In Virgen del Socorro, there are around 175 children with and without disabilities. Children in the institution had no way of expressing their personalities; all the girls had short hair and wore the same blue uniform as the boys. There was no individualized food plan based on the nutritional needs of each child. Some of the children could feed themselves, but the caregivers fed everyone with a bottle filled with a type of porridge.

Virgen del Socorro has several buildings, each with 3 to 4 floors and a central courtyard. People with disabilities are divided into buildings based on their age and sex. In each of the buildings and floors DRI visited, all children with disabilities were tied to chairs around the central patio, regardless of their disability or degree of mobility. Some of the children we observed could walk, so they tried to move the chair with their feet. We noticed that some of them, besides being tied to their wheelchairs, were also tied to the railing. The youngest children were in a room also tied to wheelchairs, watching television.

Albergue del Hermano Pedro is a private institution that houses 65 children with disabilities. In this institution, DRI also found minors with disabilities tied up. In the "rehabilitation" room there were 4 teenagers tied with their hands behind their backs while they were lying on mats.[84]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has found that prolonged restraints are "practices that have been linked to muscular atrophy and skeletal deformity"[85] According to Juan E. Méndez, former Special Rapporteur on Torture, this practice can “cause muscle atrophy, deformities and even failure of vital organs, and aggravates the psychological damage."[86] The former Rapporteur has maintained that "any restraint on people with mental disabilities for even a short period of time may constitute torture and ill-treatment,”[87] and may amount to torture.[88]

In one of the buildings at Virgen del Socorro that housed teenagers with disabilities, DRI observed two rooms designated as isolation rooms. During the visit, DRI also saw a cage where two girls had been locked up. According to staff, in each building there are cages where the children are locked up when “they become aggressive or are having a crisis. They are isolated while it passes."[89] Albergue del Hermano Pedro also has a cage where minors are kept.[90] Juan Méndez, former Rapporteur on Torture, stated that "the imposition of the regime of isolation on minors, whatever their duration, is a cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or even torture.[91]

E. Infanticide

In addition to facing abandonment in institutions due to lack of resources and support, children with disabilities also face stigma and could be facing infanticide. Further research is needed to document the extent of this problem. According to the staff from an orphanage DRI visited, infanticide of children with disabilities occurs in Guatemala. One of the main drivers of infanticide in Guatemala is “community rejection of children with disabilities” based on cultural and religious beliefs; in Guatemala, disability is considered a "punishment" so "you have to let the child die."[92] The staff told DRI that on average, he hears once a month that a child with a disability has been killed; “some have been strangled or left to starve to death.”[93]

In accordance with the CRPD, States Parties must reaffirm "that every human being has the inherent right to life and shall take all necessary measures to ensure its effective enjoyment by persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others."[94] Under Article 4(e) of the CRPD, Guatemala has the obligation “to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination on the basis of disability by any person.” Guatemala has the responsibility to fight discrimination against children and persons with disabilities. Fighting discrimination is necessary to guaranteeing the right to life (Article 10) as children who face stigma may be at risk of being killed.

F. Arbitrary judicial orders for confinement of children

All private institutions visited by DRI have at least one child who was sent there by court order. According to Guatemalan legislation, judges may send children to institutions when they are in need of protection.[95] However, the director of ABI, a public institution, stated that institutionalization is an automatic response from the judges: "the first thing they [the judges] do is institutionalize and then investigate."[96]A social worker from Casa Bernabé, a private institution, stated that judges do not explore alternatives in the extended family or in the community, “their automatic reaction is to send the children to institutions.”[97]

With adequate supports, children could remain in the family and in the community. Casa Bernabé has a program called “Familias Unidas” which “works with the Guatemalan judicial system to determine if family reunification is possible. The program works with the biological and extended families to equip them to take care of their children and follows up on them and the child.”[98] According to Casa Bernabé 30 children that were sent through a court order have been reintegrated to their families.

Under the CRC and the CRPD, Guatemala has an obligation to guarantee the right of children to live in a family and in the community. Guatemala must review all court orders through which children have been sent to institutions in order to assess whether they can be reintegrated to their biological families, to an extended family, or to substitute families in the community. Likewise, Guatemala must train judges so that the immediate response to cases of neglect is not institutionalization. Instead, judges must look for alternatives in the community including provision of support, training, and services to families. In case it is necessary to temporarily separate the child from its family, judges should investigate if there are alternatives in the extended family that can take care of the child in their community.

III. How funding perpetuates segregation and abuse

A. International funding and voluntourism

Voluntourism is the term used to describe travelers and tourists who want to “give back” or “do something good” while they are on a vacation or holiday.[99] Most often these are short volunteering stints – a day to one week –in developing and poor countries like Guatemala.

According to a 2014 report on international volunteering in Guatemala, an estimated 2 million tourists visit the country every year. Students on school break, retirees, families with small children, and faith based groups pay travel agencies specializing in arranging volunteering opportunities for a fee of hundreds or sometimes thousands of dollars. By far the most popular volunteer destinations are orphanages.[100]

As a result of their popularity with volunteers and the donations they bring in, owning an orphanage has become a booming business – where children are the commodity. Unfortunately, few if any volunteers are aware that up to 95% of children living in orphanages are not orphans at all and have at least one living parent and extended family.[101] Children are pushed into these facilities most often due to lack of supports for poverty or disability. In Guatemala, 50% of children under 5 years old are malnourished.[102] Poor and desperate parents, hoping that their children will have a better life, are seldom aware of the dangers of putting children into residential care.

No matter how clean and modern an orphanage may be, growing up in residential care has a negative impact on children’s health and their physical and emotional development. Children’s rights and social science research has shown that children need the love of a family and that long-term institutionalization is harmful to their cognitive and social development.[103] The volunteers themselves also represent a risk to the emotional wellbeing of the children. Volunteers that come and go constantly create and break emotional bonds with the children, which leads to attachment disorders in the children.[104] The Trafficking in Persons report from the US State Department found that “volunteering in these facilities for short periods of time without appropriate training can cause further emotional stress and even a sense of abandonment for already vulnerable children with attachment issues affected by temporary and irregular experiences of safe relationships.”[105]

Locked away and without the protection of family and community, children are at a much greater risk of exploitation – sexual and physical abuse and trafficking for labor and sex have all been documented by DRI in orphanages around the world.[106]

Children without disabilities – who grow up in orphanages and, after “graduation” around the age of 17, are left to fend for themselves – are likely to commit suicide, become drug addicts, commit crimes, and become sex slaves at exceptionally high rates.[107] In most cases, children with disabilities will spend their entire lives in orphanages and then adult institutions.[108]

Additionally, there is an intersection between voluntourism and child sex tourism[109] as volunteers have unfettered access to children and criminal background checks are only occasionally completed.[110] In one study, out of 20 companies arranging voluntourism trips to Guatemala orphanages, only 3 conducted background checks. Some orphanages even allow volunteers to sleep in the same rooms as children.[111]

The Trafficking in Persons report from the US State Department found that:

“it is rare that background checks are performed on these volunteers, which can also increase the risk of children being exposed to individuals with criminal intent. Voluntourism not only has unintended consequences for the children, but also the profits made through volunteer-paid program fees or donations to orphanages from tourists incentivize nefarious orphanage owners to increase revenue by expanding child recruitment operations in order to open more facilities. These orphanages facilitate child trafficking rings by using false promises to recruit children and exploit them to profit from donations. This practice has been well-documented in several countries, including Nepal, Cambodia, and Haiti.”[112]

International children’s rights standards have shifted away from institutions to supporting children in a family environment.[113] However, in many countries the outdated model of institutionalization remains prevalent, and most of their funding comes from international donors and voluntourism. A UNICEF study into institutions in Guatemala found there are 133 registered institutions, 95% of which are private, with their main source of funding coming from sponsorship and fees charged to volunteers.[114]

DRI started monitoring the situation of children with and without disabilities in Guatemalan institutions in 2016. DRI visited five institutions in Guatemala that accept volunteers: Hope of Life, Casa Bernabé, Hope for Home, Dorie’s Promise, and “Fundaniños”. During our visits DRI found that international donations through sponsorship programs and volunteers are a significant source of income to these orphanages.

Several of the institutions visited by DRI are receiving excessive amounts of money – up to $10 million USD per year, from fees that they charge volunteers – a lucrative business compared to the average annual income of most Guatemalans, which stands at less than $3000 USD.[115]

Through the fees they pay and donations that volunteers continue to send long after their week with the children is over, volunteers are unknowingly perpetuating the cycle of institutionalization by making institutions profitable. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, “institutional care in early childhood has such harmful effects that it should be considered a form of violence against young children.”[116] Until donations are redirected to help vulnerable families rather than supporting orphanages, the violence, damage and abuse to children separated from families will continue.

In 2018, DRI also visited a shelter for trafficked victims that receives volunteers. DRI is especially concerned about the use of volunteers in a facility for girls who are survivors of abuse and trauma. Being placed under the care of non-professional volunteers who come and go does not support their needs for establishing stable bonds with carers —and may have a re-traumatizing effect on these children.

Hope of Life

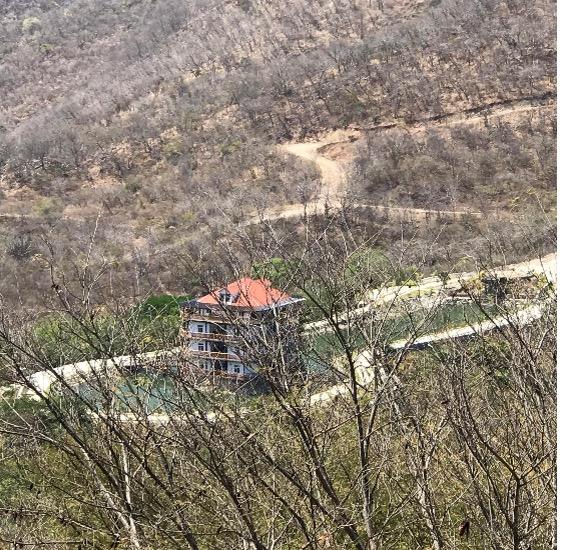

Hope of Life orphanage is in a very remote area, a 6-hour drive from Guatemala City, located atop of a mountain – land owned by the institution. It is a faith-based facility that accepts volunteers from churches in the United States and Europe. There are 195 children in the facility, of which 125 do not have disabilities. Around 60 of the children have disabilities, and 40 of the children with disabilities are survivors from Hogar Seguro, where 41 girls died in a fire in 2017.

Hope of Life accepts volunteers directly through their website, all year round. Volunteers stay at the orphanage for a week and can choose between three different levels of accommodations: the “significance package” – $750 (plus airfare); the “transformation package” – $850 (plus airfare); and the “dream-makers package” – $1,000 (plus airfare).[117] The least expensive option offers volunteers a dorm-style room with bunkbeds, while the most expensive rooms available are “air conditioned business rooms” with private bathrooms.[118]

According to the legal spokesperson at Hope of Life, during high season (Easter, summer and Christmas), they receive 400 volunteers on average per week.[119] That is twice the number of children at the institution. During low season, the organization receives around 150 volunteers per week. The average cost to volunteer at the orphanage is $850 a week and the organization makes close to 10 million USD a year from volunteers, with a total budget of almost 19 million USD. According to Carlos Vargas, the director of the organization, in an interview with ContraPoder magazine, most of the income from the organization is generated from volunteers.[120]

Hope of Life also seeks to find sponsors for the children at the orphanage. According to its website, a donation of $35 a month will “completely transform the life of an orphan who has nothing today. Your gift will give them a home. A loving family around them. An education, food and medical care.” Sponsorship is also an important part of the income of Hope of Life and it has been a very successful model to raise money. Hope of Life is now seeking sponsors for children not only in Guatemala, but also in orphanages in Haiti.[121]

DRI visited Hope of Life four times over the last four years. On our last visit we observed the living conditions of the children and the volunteers. The contrast between the areas where the volunteers stay and where the children stay is startling.

The volunteers’ quarters look like a resort, there are several swimming pools, a zoo with lions and tigers and large dining areas where they are offered a buffet for their meals. Those paying $1,000 stay in a 4-story building with air-conditioned luxury rooms surrounded by an artificial lake.[122]- DRI investigator

The areas where the children live differ substantially. Seventy-two children without disabilities live in the “Transformation Village,” consisting of nine houses. Each house has two small rooms where 8 children sleep. The houses have a small living room but are not air conditioned. Children spent most of the day outside as the buildings were very hot.

The conditions and care for the survivors with disabilities from Hogar Seguro are inadequate. They are in a separate building that has 4 rooms. Three of these rooms house 33 children with up to 10 children in a room.

The rooms where children stay are mostly barren except for a few toys and the cribs where the children with disabilities sleep. There is no air conditioning and they spend most of the time in the rooms. According to staff, they only go out twice a day for 10-15 mins. – DRI investigator

This lack of stimulus and attention causes some of the children to become self-abusive.[123] During our March 2018 visit, DRI saw a boy from Hogar Seguro who was hitting himself. He wanted to go out for a walk and was trying to get out of the room. Instead of taking him out, staff placed him in a high table. According to staff, he was scared of being on top of the high table and could not get down on his own. So long as he remained on the table they did not have to deal with him. However, the child looked scared and frustrated, and started crying and hitting himself in the head. Staff did nothing to stop this.

The Hope of Life campus also has the San Lucas Hospital on the grounds, with a capacity to treat 100 children. The hospital specializes in malnutrition and it is where children are brought as part of their “baby rescue” program. [124]

We go up to the mountains every day and usually come down with four, five, up to ten babies. Mothers won’t bring them down because they don’t have the money. – Carlos Vargas founder, Hope of Life.

Volunteers travel for hours by truck, then boat and finally by donkey or on foot to get to the babies living in remote, mountainous villages and to bring them back to the campus nutritional center.

On average babies stay two to six months and according to Hope of Life promotional videos, volunteers and mission groups have removed “almost 1000 babies in one year.”

Removing children from their families and communities to transfer them to a location that will be difficult to access for the families – according to staff “it can take hours for the families to get to the hospital,”[125] especially given how poor they are[126] – is traumatic for the child.[127] It can also lead to permanent separation of the child from the family. According to staff at Hope of Life, some babies who are “rescued” never return to their families and are put in the facility’s orphanage.[128]

Staff also told DRI investigators that babies and toddlers who are returned to their families, once they have been fed and nourished, are sent back with a follow up plan to prevent further malnutrition.[129] However, given that, according to staff, most of the children come from families living in “extreme poverty,” children are at risk of again becoming malnourished and removed from their families. The model of Hope of Life is not a sustainable one and it puts the children at risk of separation and abandonment.

Dorie’s Promise

Dorie’s Promise is another faith-based orphanage that receives large sums of money from volunteers. It is located in the middle of Guatemala City, in one of its most exclusive neighborhoods. At the time of DRI’s visit it housed 36 children, all of them referred through a court order according to staff.

The institution has three houses. The children live on the first floors of two houses. Each floor has three small bedrooms and a living room that is used as a bedroom, due to the need for space. Around eighteen children per house sleep in the three bedrooms and one living room and they are visibly overcrowded. The third house is left for the use of the volunteers only.

On its website, Dorie’s Promise states that they provide personalized care to the children, with 1 staff person for every 4 children. When DRI visited, we did see that the staff ratio is 1 to 4, but the staff includes not only caregivers but also cooks and cleaners. DRI stayed for an hour with the children alone and there were no caregivers around that were solely there to look after the children. Instead they were busy cooking and preparing for the volunteers that would come in the afternoon.

DRI observed that the children were very aggressive to each other. They were constantly fighting and some of them ended up crying. At that point a staff person came, shouted at the children, grabbed a child by the arm, and sent him away.

Dorie’s Promise accepts volunteers at the institution for one week mission trips and can accommodate up to 30 volunteers per week.[130] Some weeks, especially during the summer, are fully booked. The cost to volunteer – not including airfare – is $1100 USD per person. The potential earnings generated for the orphanage are over $1,000,000 USD per year. Its other source of income is sponsorships. According to staff, once the volunteers leave, many of them continue to sponsor children through the website or encourage their friends and family to do so. According to the website you can sponsor a child for up to $750 a month – totaling $9,000 a year. This is almost six times the average annual income of a lower middle class family in Guatemala, according to data from the World Bank.[131]

There are little or no requirements – other than paying the compulsory fee – to visit, play, and have access to vulnerable children at Dorie’s Promise:

No education, training or experience required. No language requirement. Participants age range Elementary, Jr. High, Sr. High, College, Adults, Seniors. – Website, Forever Changed International, organization which arranges mission trips to Dorie’s Promise.

Dorie’s Promise volunteers are in charge of organizing activities and games with the children. They usually bring toys and candy for the activities. When DRI was visiting the institution, a group of around 25 volunteers had come from a church in Michigan, United States. The woman coordinating the trip said that they have been organizing groups to come to Dorie’s Promise for the past 10 years. Her church also sends a group of around 30 people during the Christmas holidays.

Volunteers at Dorie’s Promise are there to entertain the children as much as the children are there to entertain the volunteers. The children are encouraged to participate in the activities organized by the volunteers. Staff also urge the children to engage with the volunteers. The more attached volunteers feel with the children, the more likely they will continue to support the facility after they leave. During DRI’s visit, one girl remained inside the house. A DRI investigator asked her if she did not want to be outside with the volunteers to which she responded that she felt very tired. The person in charge of the volunteer group from Michigan told DRI that they have been trying to come in March because over the summer “it is team after team after team and the children get tired.”

The children get tired not only from engaging with the volunteers, but also from engaging with different people every week. Forming attachments with different people on a weekly basis can be emotionally exhausting and can also lead to attachment disorders.[132]

Carlitos, a 5-year-old boy, greeted us at the door and approached one of DRI’s investigators, held her hand, and immediately asked “is this my new mommy?” He tried to stay close to the investigator the whole time we were there, sat on her lap and held her hand. – DRI investigator.

Children at Dorie’s Promise have been separated from their families, which already places them at risk of trauma and attachment disorders. Being exposed to total strangers coming and going and constantly forming and breaking bonds only worsens this risk.

Most of the children were hugging the investigators constantly, and they wanted their undivided attention until they found other things to do or other people to get attention from. They were also hugging and seeking the attention of the volunteers. This was reinforced by the candy and the gifts they got from the volunteers every time they approached them or played a game with them.

There were two children with disabilities who, on the other hand, were subjected to emotional neglect in the institution. According to staff, neither of them attend school. There was one child who, according to staff, is aggressive so they essentially lock him in a room. He cannot get out for long periods of time and remains isolated from the rest of the children. When the volunteers were playing with the children, the children with disabilities were noticeably not included and remained inside the house.

Casa Bernabé

Casa Bernabé was founded 30 years ago by an American. There are 140 children in the institution, living in nine houses. Children are sent to the institution via a court order. According to staff that DRI interviewed, 95% of the children have a parent and an extended family. In several of the cases, the extended families could take care of the children if given the opportunity. However, staff complained that the court system in Guatemala, in practice, automatically sends children in need of protection to institutions.

Casa Bernabé also accepts volunteers, 90% of whom, according to staff, come from the US. Volunteers pay $250 a week to stay at the institution. According to its website, it can host up to 40 volunteers at a time. Staff told DRI that for 10 weeks in the summer, the institution is “fully booked,” and the rest of the year they receive around 20 volunteers per week. This means that the institution could make around $300,000 USD a year from volunteers.

B. Misplaced government priorities

Studies around the world have shown that supporting children in institutions is much more expensive than supporting them to live with their families. Based on information provided to DRI by authorities at the ABI institution, the amount the government spends in Guatemala to support children in that facility is 45 times higher than what it now provides for families to keep children with disabilities at home at part of the government’s family support program.[133]

In practice, the amount provided by the government’s family support program is so small that it does not help many parents keep their children at home. Authorities at ABI explained to DRI that the funding for families would barely cover the cost of transportation to see doctors at a community center – but it would not cover any of the cost of care or treatment. If a child needs any form of mental health treatment or support, many families who wish to keep their children at home are forced to institutionalize their sons or daughters – just because they lack the funding to pay for the cost of support at home. Even for children who do not need specialized care, but just need a support person to help them, parents may be forced to stay at home or give up their job. Families who cannot afford to have a parent stay at home have no choice but to place a child in an institution.

This allocation of resources demonstrates that Guatemala continues to support institutionalization at the expense of families – especially when it comes to children with disabilities.